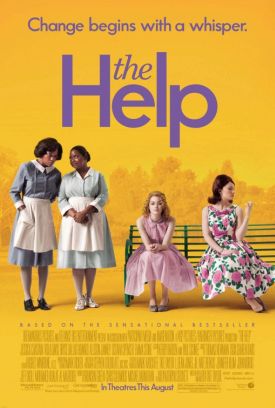

Help, The

What a good thing, I’m sure we can all agree, that oppressed black people in Mississippi in 1963, though they lost Medgar Evers, were saved in the end by that cute white girl just out of Ole Miss called Skeeter. What? You don’t remember that part of the story? That’s because Skeeter is a figment of the imagination of Kathryn Stockett who was born too late for the heroic days of the civil rights movement and projects her own girlish liberalism and compassion for black suffering, not to mention her own literary ambition, onto the imaginary Skeeter, a cub reporter in charge of the cleaning-tips column for housewives of the Jackson Clarion-Ledger. Skeeter, though beset with boyfriend problems and racist girlfriend problems and a mother with cancer, not to mention a missing black nanny about whose fate her mother is maddeningly vague, makes the sort of contribution to racial progress that she, Ms Stockett, would doubtless have made, if only she had had the opportunity, back in the day.

As this fictional contribution comes in the form of a book called The Help (just like Ms Stockett’s book) telling what purport to be the untold stories of Mississippi’s black female servants (just like Ms Stockett’s book) — a book which she dashes off as her brilliant literary debut resulting in fame and fortune (just like Ms Stockett’s book) — we can hardly avoid seeing the thing as politically correct wish-fulfilment fantasy. Which it undoubtedly is. Not that that appears to matter to anybody. What is interesting to me about the phenomenon of Ms Stockett’s block-busting best-seller and, now, the Dreamworks film that has been made out of it by Tate Taylor is the extent to which people these days are prepared to accept what I regard as an outrageous interpretation of this bloody and eventful chapter of American history as a journalistic romance, just like Vietnam or Watergate.

If, like most people, you get your history from the newspapers, you may well believe that David Halberstam and Neil Sheehan (and Daniel Ellsberg) of The New York Times were the heroes of Vietnam, just as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post were the heroes of Watergate. Thus, perhaps, you will be easily persuadable that it must have been some journalist revealing discreditable secrets who can best be cast in the role of the hero (or at least a hero) of the civil rights movement — in spite of the fact that we have always known the evils of segregation and racism in the South were no secret even to those who fought so hard to prolong and uphold them. Doubtless there were lots of respectable white folks, like all the ones in this movie apart from Skeeter (Emma Stone) and the beautiful but vulnerable social outcast Celia Foote (Jessica Chastain), who were willfully blind to details of the sufferings and indignities endured by their black servants, but this was more of a symptom than a cause of those sufferings and indignities.

At any rate, the idea that these could have been alleviated by being poured into the sympathetic ear of a 20-something budding journalist, as interested in finding a boyfriend and in writing for New York glamor magazines as in her subjects, is ludicrous. As for the film’s central episode involving the serving of a chocolate pie with unmentionable contents (though here they are unfortunately mentioned) to the racist witch Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard), Skeeter’s ex-best friend, by her former cook, Minnie (Octavia Spencer), in retaliation for the latter’s dismissal after using the white folks’ bathroom instead of venturing outside in a hurricane to the more Spartan accommodations provided for their colored help — well, let’s just say that it lacks a certain something as a symbolic embodiment of racial conflict in the Jim Crow South before the age of enlightenment in which we are nowadays so lucky to be living.

That we cling so hard to this belief in our own enlightenment is one reason why that unbelievable incident, like the unbelievable movie as a whole, is apparently taken seriously by the throngs jamming the multiplices to see it. Like Ms Stockett and the makers of the movie version of her book, too many of us are are more proud of our own liberal-mindedness than we are interested in the truth about those who lived before liberal-mindedness became so readily and cheaply available to us as it is today. That’s why the liberalism of The Help has a sort of rote quality to it. The movie even throws in an anticipation of the self-esteem movement as black nanny Aibileen Clark (Viola Davis) teaches her neglected white charge: “You is kind. You is smart. You is important.” You is doing the child no favors, lady. But there’s some more folk wisdom for you from the latest of Hollywood’s favorite Magic Negroes. Such smugness, it’s true, is not so bad as bigotry and racism, but neither is it all that much more attractive.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.