Behind the Headlines

From The American SpectatorHere in Washington, it is hard to go anywhere where tourists also go, such as the Metro, without seeing advertising for one of our capital city’s most successful tourist traps, which grandly calls itself the International Spy Museum. All of it is marked with the museum’s motto: “Nothing is what it seems.” The more you look at it, the more nonsensical that claim would seem — that is, if it were a claim and not a slogan. On the contrary, for most of us, for most of the time, nearly everything is what it seems. At least, so it seems to those of us who are not among the increasing number of people who hope to make a profit out of showing people that it isn’t, because they know what no one else does. This claim to secret information is of course what spies share with the media, conspiracy theorists and intellectuals, and those who patronize the supposed possessors of this information are very often prestige-seekers, eager only to claim a precedence over their neighbors by virtue of knowing something they don’t know. The opportunities for chicanery and fraud are obviously enormous, as the curious history of the “birther” and “truther” narratives in recent years has shown.

Yet even the craziest of stories have some truth value if enough people are prepared to band together in an unspoken pact to believe in them. If these belief-groups are otherwise identified as privileged in some way, say by victimhood or persecution, they are likely to be unmolested in possession of their voluntary absurdities. Thus, according to some estimates, a third of American blacks believe that AIDS was formulated in government laboratories to decimate the black population. Well, since quite a lot of other things have been done by American governments to victimize blacks, nobody is going to spend a lot of time trying to disabuse them of the notion, even if nobody outside their community believes in it either. Believing as they do has other benefits for them with which the mere knowledge of the truth can hardly hope to compete.

Lately, however, the claim to victimhood has itself become privileged information. The protestors calling themselves “Occupy Wall Street” and their imitators across the country and around the world are making a claim to victimhood against corporations or banks or Jews or “the rich” or some combination of them which mainstream society, long accustomed to recognize these things and people as respectable and even admirable, does not recognize. If they are themselves dysfunctional and unemployable in the corporate world, someone other than themselves must be to blame. Who else but the corporations? With luck and a bit of cold weather, the protests will have fizzled out by the time you read these words, but their claim to legitimacy lingers on, backed by the increasing conviction with which people regard the Spy Museum’s claim that nothing is what it seems. Those big corporations might seem to be producing goods and services that people need and want while providing employment to millions, but underneath that benign exterior there must be supposed to lurk the oppressive power that is preventing 26-year-old theatre-majors with $50,000 in student loans from enjoying the American dream, as they know they are entitled to do.

|

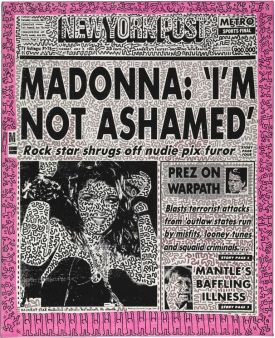

That kind of thinking is an addiction and must feed itself with the arcana of conspiracy as retailed by the media, respectable and non-respectable, who have in common a pecuniary interest in promoting the belief that nothing is what it seems. But it also requires a constant reinforcement of its most basic assumption from the arts, which are as always the purveyors of our most cherished myths. As the “Occupy DC” protestors gathered in Freedom Plaza in late September, there was opening at the National Gallery just a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue an exhibition called “Warhol: Headlines.” All or most of Andy Warhol’s canvases and other installations ripped, literally, from the headlines were gathered in one place for the first time to demonstrate how the artist sought, in the words of one of the contributors to the exhibition catalogue, to “dramatize the attempts — and subsequent failures — of both contemporary painting and the mass media to structure or give narrative to everyday life.”

Savor, for a moment, that idea of “giving narrative to everyday life.” It’s not, of course, that there are not narratives a-plenty in the news stories from the papers which Warhol reproduced, often in fragmentary form. It’s that those narratives are multiple and superficial. Nothing is what it seems, however, and so Andy Warhol provided new and hidden narratives to these simple tales of disasters and celebrities interspersed with the kind of commercial art in which Warhol got his start by giving them new contexts. The whole show amounts to one facet of Warhol’s customary technique of playing with context in order to alter meanings, which is what irony does. A Campbell’s soup can means one thing in the supermarket and quite another in Andy’s silk-screened repetitions hanging on a gallery wall. Yet, says Philip Kennicott of the Washington Post “Warhol was no irony-soaked provocateur mindlessly importing pop pizzazz into the sanctums of high art for pure shock value. He was strategic, intelligent and brilliantly adept at analyzing and indicting the world we live in today, a world he seemed to both predict and forge through games of representation we now know by the encompassing shorthand: Warholian.”

The idea of “indicting the world we live in today” — as if it were possible to live in some other world — is evidence of sloppy thinking on Mr Kennicott’s part, but it is a customary sloppiness of some mythic significance. “Elton John: I want Zachary to grow up in a world without homophobia,” headlines this morning’s Guardian. Good luck with that, Elton. Those protestors, too, don’t want to live in a world where — well, where bad things happen, like mean bosses and moms who kick you out for smoking dope. Mr Kennicott is doubtless right to give Andy Warhol some credit for the ubiquity of this conceit since he did, indeed, make an implicit claim through his art to a proprietary “world” of his own as a platform — not so much for criticism of the boring old world of those who read newspapers unironically but for mere anarchic mockery of it and them. If only we could all be as clever as Andy, we should none of us have to endure the pain of living life as it must be lived in the world that they used to call real. Now, however, the exciting quality of the Warhol fantasy world has lost some of its “pizzazz,” since fantasy worlds have multiplied to the point they have a quarter century after his death, as we can see from a stroll down the street to Freedom Plaza.

|

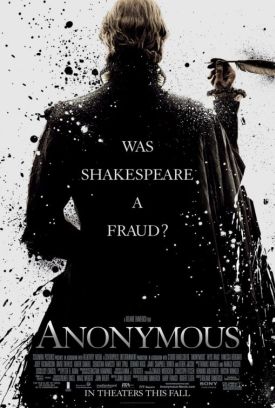

Yet since art, including popular art, declared its independence from reality, what choice do we have but to live in the new reality of endless fantasy worlds? We have to get what pleasure we can from them, at any rate. What struck me about the movie Anonymous was how it made no attempt to make a serious case for the Oxfordian authorship of Shakespeare’s plays, assuming there is one, by integrating its “narrative” with the known facts of the lives of Shakespeare and the Earl of Oxford and Ben Johnson and Christopher Marlowe and Queen Elizabeth I and William Cecil, Lord Burghley. As, I suppose, not one in a hundred of the expected audience for the film will know or care anything about those facts, Roland Emmerich, the director, and John Orloff, the screenwriter, appear to have decided to make everything up and abandon any pretense of plausibility or truth. Thus, for example, the film has the Queen (Vanessa Redgrave in age, Joely Richardson in youth) giving birth to a string of bastard children, at least one of them incestuously, as if our discovery of the joys of sexual laissez-faire in the 1960s had happened four hundred years before it did — and without anyone’s knowledge except the scheming villain, William Cecil (David Thewlis) and his bunch-backed son Robert (Edward Hogg), said to be the model for Richard III.

But of course this secret — as preposterous as the idea of Shakespeare’s true identity being a secret for hundreds of years — is the best thing about it for those who have the addiction catered to by the Spy Museum. That’s why those who see the picture will want to see it and why such luminaries of the English stage as Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance, to say nothing of the Misses Redgrave and Richardson, have lent their names and their talents to such a sorry farrago of historical and literary nonsense. It’s not really a movie about Shakespeare or anyone who might be claimed to be the author of his works but about those doing the claiming: their talents, their intelligence, their superiority to the ruck of mankind who accept the world of appearances, mostly, at face value because they haven’t the wit to know, as those of the Ruling Class do, that “nothing is what it seems.”

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.