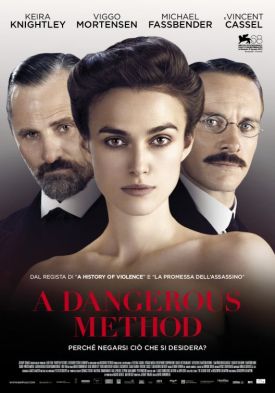

Dangerous Method, A

Here’s what I liked about David Cronenberg’s new movie, A Dangerous Method, loosely based on the early history of psychoanalysis — as filtered through the work of psychologist cum historian John Kerr (A Most Dangerous Method: The Story of Jung, Freud, and Sabina Spielrein) and playwright Christopher Hampton (The Talking Cure) — in spite of its having reduced that history to little more than a celebrity soap opera. He sets out four different theories about the job of what used to be called the “alienist” or, as P.G. Wodehouse would put it, “the loony doctor” which are still held today. The watchword of Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen) is the injunction: “Whatever you do, give up any idea of trying to cure them.” Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), Freud’s younger disciple, fitfully accepts this view of his profession but is too much the enthusiast to accept it for long: “It’s no good showing the patient his illness squatting like a toad in the corner. . . We must teach him to reinvent himself,” he says. Jung also has some sympathy for the view of another renegade Freudian, Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), who anticipates some of the radical psychiatry of the 1960s by commanding: “Never repress anything” — and by living his own life by that creed with predictably disastrous results.

Like many a lesser man, Jung allows himself to be persuaded by Gross’s creed only to the extent that he gives himself permission thereby to do something which, without it, he knows very well to be wrong. That is, he indulges his lust for a young patient, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), whom he has cured of hysteria and whose love-by-transference for himself is liberally peppered with masochistic urges left over from the paternal abuse that caused her mental illness in the first place. When Jung tells her that his love-making with his wife is “tender” she replies: “With me I want you to be ferocious; I want you to punish me.” And, reader, he does! Foreplay for them appears to consist of his belting her with, er, a belt while she moans with apparently orgasmic pleasure. Is he just politely obliging her kinky desires? Or does the man who says more than once that there are no coincidences find an answering sadism in himself to complement her masochism? That seems by far the more likely explanation, yet the film appears to have no other interest in the kinky side of Dr. Jung. A curious omission.

Miss Spielrein goes on to become a psychoanalyst herself and a pupil of Dr Freud after Jung guiltily rejects her. Hers is the fourth psychoanalytic path, as she tells a surprised Freud that, in her view, sex is not motivated by gratification of the ego but by the desire for self-annihilation. “True sexuality demands the destruction of the ego,” she says, which is “the opposite to what Freud proposes.” But the film doesn’t take a position on this difference either. The salient moment of Sabina’s relations with Freud comes when the great man tells her that there was never any future for her in a relationship with Jung and that her dream of a “blond Siegfried” (she and Jung are both enthusiastic Wagnerians) was never going to come true. She should “put no trust in Aryans,” he tells her. “We are Jews, Miss Spielrein, and Jews we shall always remain.” There is, then, a nice dramatic irony in the fact that — as we are informed by a card at the end — she was later to be shot by the Nazis.

By this time, Freud has broken off his once close relations with Jung over the latter’s “mysticism” (as he sees it), which threatens the whole scientific foundation of psychoanalysis. A century later, long after that foundation has been called into question for quite different reasons and psychiatrists have mostly moved on from “the talking cure” to prescribing psychotropic drugs, it’s a little hard to see the point of the Freud-Jung quarrel except as a quasi-Oedipal conflict — O, the irony! — that might provide an operatic plot if only somebody died in it. In place of individual tragedy, Mr Cronenberg, working from Mr Hampton’s screenplay, places a Jungian premonition — he accepts him as some kind of clairvoyant, it seems — of the First World War, still a year or so distant at the movie’s end, which was to sweep away Old Europe and the system of civilized repression on which (they say) it was founded.

That seems to me to be a cheap way of borrowing significance for a story that otherwise might seem to lack it. More importantly, it obscures the still vital and still unanswered question of whether we ought to live with our neuroses or to try to cure them. Mr Cronenberg might argue, as some liberal pacifists do these days, that the war, like all wars, was the product of bottled-up passions which could be released in much less harmful ways by a therapeutic approach. His earlier film with Mr Mortensen, A History of Violence seems to me to be based on some such view of the world. If only we could find the root cause of violent or anti-social acts or of mental illness we could prevent them. Maybe they even have the same root cause: repression. The character of Otto Gross tells us that he’s not going to fall for that one, but without some such inevitably facile solution to its problems, the film really has nowhere to go apart from this vaguely portentous ending and a lingering memory of the lovely Miss Knightley in Victorian-style undies being whaled on. Whatever turns you on, I guess.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.