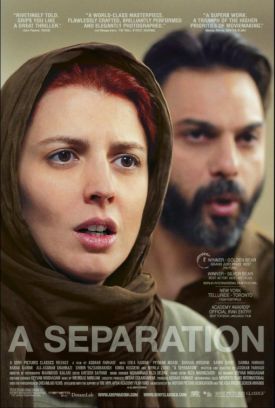

Separation, A (Jodaeiye Nader az Simin)

It’s been a while since I’ve seen an Iranian film, though I am always eager to see them. Most in recent years have shown the influence of Abbas Kiarostami (A Taste of Cherry), who has a highly visual style with long, slow takes and spare dialogue. Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (Jodaeiye Nader az Simin) is a very different bowl of cherries. Tautly plotted and full of passionate speech, it engages the mind more than the eye and poses a moral dilemma, or a series of interlocking moral dilemmas, unsparingly but subtly limned, rather than the stark existential crisis of a Kiarostami film. And although the picture is very firmly set in the social, political and religious context of contemporary Tehran, its morality has a poignantly universal relevance. Too many reviewers and interviewers focus on Mr Farhadi’s sometimes troubled relationship with the Iranian government, as if there could be nothing out of Iran of any interest which did not directly challenge its clerical authorities. But to my mind one of the best things about this film is that it makes all such political questions seem trivial and irrelevant.

The separation of the title is between Nader (Peyman Moadi) and his wife, Simin (Leila Hatami), who desperately wants to leave the country. Somehow — how is never made clear — she has obtained permission to go, but Nader refuses to accompany her as he has to care for his senile father (Ali-Asghar Shahbazi), a job which seemingly has fallen to her lot hitherto. “He doesn’t even know you’re his son,” insists Simin before the magistrate whom she is petitioning for a divorce.

“But I know he is my father,” replies Nader.

The magistrate tells them that they are wasting his time. Theirs is a small problem, he says — and it is, too, in the sense that it is really quite simple. If she wants to go, she should go; if he needs to stay, he must stay. Neither can impose his or her will on the other. But we soon discover that there is a complication. The couple’s 11-year-old daughter Termeh, played by the director’s own daughter, Sarina Farhadi, insists on staying with her father, and her mother will not leave the country without her. In fact, it appears that it is largely for the daughter’s sake that she wants to go in the first place, just as it is for the sake of her parents’ marriage that Termeh wants to stay. So, instead, Simin goes to stay with her mother (Shirin Yazdanbakhsh) and Termeh fills in for her as she can in looking after the old man, who needs almost constant attention.. For when she is in school, however, Nader hires Razieh (Sareh Bayat), a poor religious woman, to attend his father.

But Razieh keeps the job a secret from her husband, Hodjat (Shahab Hosseini), a hot-tempered, unemployed cobbler who is heavily in debt. Moreover, she has to travel from a long distance away and must bring her own small daughter, Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini), with her to work. The arrival of Razieh seems to coincide with a further deterioration in the old man’s condition. When he becomes incontinent, she must call the religious authorities for a ruling on whether she is allowed to clean him up. One day Nader comes home early to find no one in the apartment but his father, who has been tied to the bed by one wrist and who has subsequently fallen out of it. Without his oxygen, the old man would soon have died. Nader also thinks some money is missing. When Razieh returns, she cannot explain where she has been, though she denies taking any money. He fires her and thrusts her roughly out of the door. The next day she suffers a miscarriage.

The film’s big question seems to be: did Nader know when he pushed Razieh out the door of his apartment that she was pregnant. He insists he didn’t. She insists he did. If the court decides he did, then he is guilty of manslaughter; if he didn’t, then he is not guilty. Guilt will mean a prison term for Nader and/or blood money to be paid to the family of Razieh — including Hodjat, whose desperate need of money means that his (and Razieh’s) incentive to lie is as great as Nader’s. Because key elements of the story have been withheld from us, we are in the position of the judge (Mohammad Ebrahimian) who has to decide who is lying. So, by the way, is Termeh, whose attachment to her father and her hopes of keeping her parents together seem to depend on her belief in his truthfulness. But the consequences of the truth in both cases can be so drastic that it is hard to work up very much moral indignation against any of those who are driven to lie — as everyone is by the time the missing parts of the puzzle are supplied and we discover the truth for ourselves.

Or almost everyone is driven to lie. The exception is Simin who is compensated, as it were, for having set the whole train of events in motion in the first place by being the only one left at the end with arguably clean hands in this heart-wrenching wrangle over love and hate and guilt and money. As a result, we are more than ever aware of the central enigma of Simin’s wish to escape, which is the only thing in the movie that remains — ironically, I think — morally unassailable. For everyone else, we are left with something approximating to the pity and terror that Aristotle said was appropriate to tragedy — which, to the extent anything can be these days, this movie is. Above all, it is like The Artist in being an example of the art of movie story-telling, something that America pioneered in the great days of Hollywood but which is now almost a lost art here. This is a movie that will break your heart, and of how many movies in the post-modern era can that be said? It is not to be missed.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.