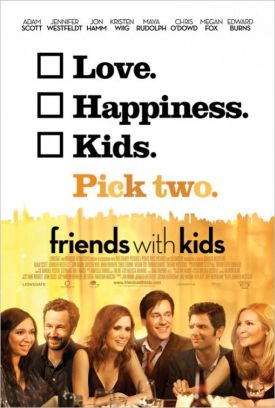

Friends With Kids

The thing I always think about movies like Friends With Kids — movies in which two people who are obviously made for each other resolutely maintain to themselves and the world that they are just good friends until the moment of epiphany when they discover they are totally hot for each other — is to wonder if such stupidity really does exist in nature or if it is entirely made up for ideological reasons. I lean toward the latter explanation. Feminists, I think, suffer from the terminal naiveté of always being ready to believe in the irrelevance of sex in human relations — even relations between lustful males and the nubile females. It’s just something they have to believe, like “the personal is the political” or “a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.” What they mean is that’s how it should be. They state it in the indicative rather than the imperative in order to pretend to themselves that what should be already is — even though it often isn’t and sometimes never could be.

But the long-delayed romance between best friends Julie (Jennifer Westfeldt, who also wrote and directed the picture) and Jason (Adam Scott) is set in a movie with much larger ambitions. This is not just a romance but an essay in the thing to which romance was traditionally a prelude, namely family formation. If the two things had never been separated by the sexual revolution, a movie like this could never have been made. And for all its many faults — about which more in a moment — it does have the very large virtue of reintroducing the two to each other and making its intended audience of hip urban singles — and those who aspire to be or are nostalgic about having been among them — to think about what still seem to some of us the natural links between romantic love and families.

Julie and Jason are part of a “Friends”-style faux family with two other couples. Leslie (Maya Rudolph) and Alex (Chris O’Dowd) lead the way in having children and Missy (Kristen Wiig) and Ben (Jon Hamm) soon follow. Eventually Julie and Jason get the idea and decide to have a baby together and share custody — they even move in together — with the stipulation that they are not in love, are not a couple, are not even attracted to each other and are still each expecting to find elsewhere the romance that has severally eluded them. But before you protest at the preposterousness of this scenario, you should know that the movie is way ahead of you. When Jason finally figures things out, he explains it to Julie: “We decided to make the kid together so we could have the romantic part later, but this is the romantic part, and all the rest was just filler.” Duh!

The “filler” includes Jason’s long relationship with dancer Mary Jane (Megan Fox) and Julie’s rather less lengthy one with Kurt (Ed Burns), about whom on meeting him she rhapsodizes: “Who knew there were men like that?” To her he seems “a real, grown-up man,” — the implicit comparison is with Jason whose taste in women runs to the bimbo-esque and who is described by his best friend, Julie, as “a pig when it comes to women” — though we are not made privy to any revisions she might be inclined to make in this opinion after their relationship breaks up. Julie’s and Jason’s attempts to make stable relationships apart from their shared one, consisting of a long platonic friendship and a child, are seen in the context of the troubled marriages of Leslie and Alex and Missy and Ben, both of which are put under enormous strain with the arrival of their respective offspring.

Right there you can see the trouble with this movie as a study of families. The kids simply get in the way of what everybody still assumes, as they did when they were single and childless, is real life. That’s also why the kids are mere props in this movie, just as they apparently are in the lives of its adult characters. At no point does Miss Westfeldt allow us to see them as anything but more or less troublesome pets. The movie actually starts from the proposition that real life is the life of these hip Manhattan singles, gathered around a table in a swanky restaurant and looking rather askance at the social faux pas of their neighbors at the next table who have brought kids into it. That’s what kids do: they ruin your social life and maybe even your marriage.

True, the movie treats them as a kind of weary inevitability for anyone with any street credibility and takes rather a dim view of the one character who, in the name of her “freedom,” flatly rejects the whole idea of reproducing. This is Jason’s slim, lithe, large-breasted girlfriend Mary Jane who says, “I could never be responsible for another living thing” — which also puts children and pets into the same category. But to the others as much as to Mary Jane, real life does not include children. Instead it consists of dating and going out with other adults for convivial and expensive meals, working and vacationing and, above all, “having sex” — all things with which children can only interfere. Especially having sex. In fact, not having sex smacks of scandal. The friends are always interested in how often each other is able to manage it, and the chief burden of parenthood is seen as the limitation it places upon one’s opportunities to copulate.

One curiosity about the movie is that its natural climax comes quite a long way before the end. The three couples, plus Jason’s girlfriend and Julie’s boyfriend, are on a skiing vacation together in Vermont, along with the kids — who as usual scamper about like puppies without leaving any human impression. As they sit over dinner together, Ben, who is depressed and drinking heavily, says that some people were just not meant to be parents. He clearly has himself and Missy in mind but, perhaps envious of Julie’s and Jason’s perfect relationship, attempts to project his own misery onto them. Jason replies with a splendid outburst in response to Ben’s pessimism which purports to vindicate his still non-sexual love for Julie as the perfect foundation for child-rearing. “I am on board with everything about her,” he says and proceeds to enumerate her many charms for him, among which is the fact that “we both think organized religion is totally full of s***.”

The idea seems to be that, as Missy and Ben’s marriage is obviously breaking down, they would be hard put to it to come up with a similar catalogue of each other’s virtues and that what’s really important in a relationship is the number of boxes such a couple could check about each other. Likes kids, check. Likes dogs, check. Thinks organized religion is totally full of s***, check. As Julie and Jason are perfectly compatible in every way but (so they are determined to think at this point) sexual attractiveness, they must have the sort of firm foundation that the ideal family should be built on. But instead of having them fall into each other’s arms at this point, the movie artificially stretches out its long charade of their supposed sexual incompatibility for another half hour before calling time and making them realize what everybody else has understood from the start, or certainly since the scene in the ski lodge.

Why do that? Maybe because the coincidence of opinion implied by their both thinking organized religion is full of s*** is being mistaken for the sort of bond that religion itself would once have made in order to bring about and sustain marriage and child-bearing. The God-shaped hole in these people’s lives is being filled, so they think, by the kind of human chemistry (or alchemy) outlined 200 years ago by Goethe in his Elective Affinities (Die Wahlverwandtschaften) which they have both got to understand before they can be together. That’s the romance that Jason is talking about in the end when he says that “this is the romantic part.” He means that they have finally collected enough points of congruence between them, including the all-important sexual one, to see the pattern and so justify the existence of the family they started on the somewhat slenderer basis of sharing similar opinions and being parents to the same child.

Once again, the poor kid is being devalued vis vis the paramount importance given to his parents’ tender psyches and the imperative of their many lifestyle preferences. That’s the reality that Miss Westfeldt’s movie cannot escape from, and Jason’s final revelation is just a way of tacking on a sentimentally satisfying ending to a portrayal of life utterly without romance — a life in which sex has been mistaken for romance and will doubtless continue to be, as we realize when Jason offers to prove his love for the girl whom, as he now understands, he mistakenly thought he was not attracted to. He does this by saying, “Let me f*** the s*** out of you to show you I am into you.” That’s the big romantic pay-off in Miss Westfeldt’s view. You can’t help but realize that this is a movie about people who don’t really know what romance is. They’ve heard of it, and they are keen to experience it; they have all kinds of theories about it and where it comes from and what it must be like. But the way they have learned to live their lives will make it forever impossible for them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.