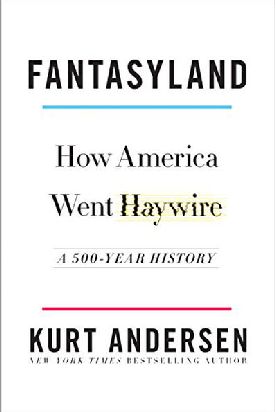

Pseuds and Artists

From The American SpectatorEight of the nine nominees for this year’s Academy Award for Best Picture were partly or wholly set in the past: one in the ‘teens of the last century, three in the twenties, one in the fifties, one in the sixties, and two in 2001-2002. If you add in the Best Actor and Best Actress categories, you also get one from the 1950s, one from the 1970s, one from the 1980s and one from the Victorian Era. Some years ago I wrote of the movies as our national family album, a chance to remind ourselves of what our country looked like in times past. American movies may not be good for much these days, but they are good for that. Hollywood provides us with this delight not merely to beguile an idle hour but to give us back something we need, something to hold on to in a changing world. The re-creation of the past is our cinematic comfort food.

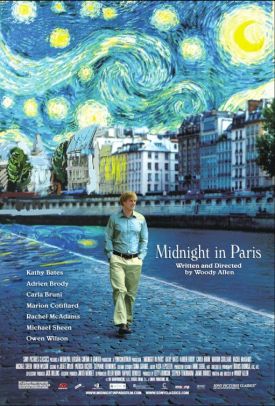

Of the three nominees set in the 1920s, two involve a double leap backward in time, first to the Paris of the entre deux guerres and then a generation earlier to the Belle Epoque. Both Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris and Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, are drenched in nostalgia, inspired — ostensibly, at any rate — by art, but they end up in diametrically opposite places. Mr Allen, though his reverence for the filmic past approaches Mr Scorsese’s, reaches the very American conclusion that history is bunk, while Hugo remains all but choked — as well as choked up — by its homage to Georges Mélies (Ben Kingsley), the French cinema pioneer, and the sense it imposes upon his life story of the power of the movies to heal and transform our lives.

Hugo, which depicts the famous train wreck of 1895 at the Gare Montparnasse in a dream sequence, itself goes badly off the rails, I think, when it over-complicates the story of Mélies with another about an orphan clock-winder living in the station and turns the whole thing into a sort of therapeutic romance with a lot of anachronistic talk about people emulating machines by being “broken” and then “fixed” — fixed, at least in part, by the art of those “wizards” which Mélies claims he and all film-makers are. The prestige of art is also conjured up in an opening sequence in which Mr Scorsese includes cameos by such artistic “icons” as James Joyce, Salvador Dali and Django Reinhardt — thus emulating Mr Allen in Midnight in Paris who, in addition to Dali, gives us Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein among many others.

|

In both pictures the famous dead faces lend tone, so that we may know the film itself is supposed to be art, having been made by someone familiar with the artists’ hall of fame. A poseur in Midnight in Paris is said to be a “pseudo-intellectual” — a term which apparently carries with it no memory of its invention by Governor George Wallace — because Mr Allen and his hero, played by Owen Wilson, aspire to be non-pseudo-intellectuals the way people used to aspire to be knights or lords. As our culture keepers and guides, these members of the cognitive aristocracy reassure us about what of the past we may rightly reverence. And rightly execrate as well, since the nostalgic impulse is always helped along by the feeling that the past is past because somebody put a stop to it and still keeps us from it.

The theme of Hugo is innocence, both of the pre-pubescent main characters and of the culture. Georges Mélies is supposed to be embittered by the loss of his movie-making business and coaxed back to life and health by the children who, it must be said, have a remarkably easy time cheering him up. Citing their example, his wife, Jeanne d’Alcy (Helen McCrory) says to Georges: “You have tried to forget the past for so long. It has brought you nothing but unhappiness. Maybe it is time to remember.”

Sure enough, Georges immediately starts remembering those happy days of movie-making in the Golden Age before World War I. “We thought it would never end,” he says mournfully, “but then the war came and youth and hope were at an end.” The end of youth and hope, only occasionally spotted since, meant to Georges that “the returning soldiers had seen so much reality that my films bored them.” Anyway, he was out of business. “Happy endings only happen in the movies,” he says. Then, to prove his point, Mr Scorsese swiftly provides him, and us, with a happy ending.

As it happens, that primal sense of the loss of civilizational innocence in the 1914-1918 war, now a cultural cliché, also figures in yet another of the Best Picture nominees, Steven Spielberg’s War Horse, in which the world-shaking catastrophe, however, has only a bit part, limping onto a corner of the stage to support the movie’s star turn by a horse. Luckily for Mr Spielberg, the inherently bathetic effect that might otherwise have been expected from such a scenario is minimized by the war’s being reduced to merely symbolic status. It is no more real to the audience, who may never have heard of it, than it is to the film-makers. And those who have heard of it will have done so only as the ultimate proof that War is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things.

Michael Morpurgo, the Englishman who in 1982 wrote the children’s novel on which War Horse is based, told Sarah Lyall of The New York Times that “In 1982 the only war in Britain was the cold war. . .But times have changed in the last 15 to 20 years. War does seem to be endemic. When it’s possible to do it, we seem to do it. It never ceases to amaze me that we fall into that trap again and again.” Doubtless it slipped his mind that Britain fought a hot war in 1982 for the repossession of the Falkland Islands after their invasion by Argentina — a fact alluded to in yet another of this year’s Oscar nominees, in the Best Actress category, Phyllida Lloyd’s Iron Lady, discussed in this space last month (see “Progressive Derangements” in The American Spectator of February, 2012). It treats that war symbolically too, as one among many reasons to cluck our tongues and shake our heads at the unfeeling ruthlessness of Margaret Thatcher (Meryl Streep) in power.

|

Actually, the only “trap” we continually fall into is the one Mr Morpurgo and others do when they make “anti-war” movies — and all war movies are anti-war now — which is the trap of thinking that war is optional and only happens through the fault of those in power who don’t try hard enough to conciliate our enemies and reassure them, as John Le Carré and Tomas Alfredson do in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy that they needn’t hurt us as we’re really just like them. Some thought Tinker, Tailor a bit hard done by not to get a nomination itself, but Gary Oldman got one as Best Actor for doing a spot-on impersonation of Alec Guinness’s George Smiley — as good in its way as Miss Streep’s spot-on impersonation of Lady Thatcher.

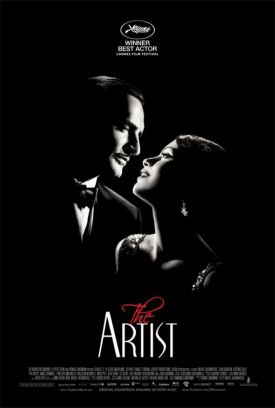

Another of the nine Best Picture nominees, The Artist, is also set in the 1920s, but there the cultural traffic is going the other way from that of Hugo. Instead of an American director imagining the long-ago French film industry, Michel Hazanavicius is a French director imagining the long-ago American film industry. There is in The Artist a similar nostalgia to Mr Scorsese’s about the early days of the pictures as well — so much so, indeed, that it is itself a silent movie, to all intents and purposes. But instead of the semi-technical discussions of film history and technique in which Mr Scorsese overindulges himself in Hugo, The Artist actually brings these things and the people who lived with them to life again — brilliantly, in my opinion — and, in doing so, raises the eternal question of the relationship between popular art and the certified, museum-quality kind.

The Artist

comes down on the side of the popular arts. Nothing could be less pretentious than its portrait of the entertainment industry more or less as it was — schlocky and sensational, with its roots in vaudeville and animal acts, one of which survives in the hero’s trademark and sidekick, a Jack Russell terrier. This is a delightful creature called Uggie who modestly makes none of the extravagant claims on our sympathy that “Joey” the horse does in War Horse. A movie like this does not depend on intellectuals, pseudo- or otherwise, either to be-garland it with Oscars or to certify it as suitable to be our “mantra” — as T.S. Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” is said to be that of Mr Wilson’s character in Midnight in Paris. Unlike that film, The Artist redeems the act of turning to the past for reassurance, rather than instruction — which itself would reassure us, if we ever cared to look, that innocence is never lost for good.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.