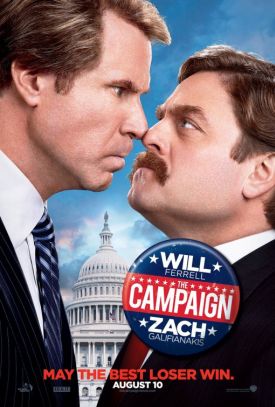

Campaign, The

Hollywood doesn’t do politics — at least not politics as it is practised in the real world. That muddled and muddy system of alternating compromise and confrontation, posturing and horse-trading, simply wouldn’t show up on the silver screen — and, even if it did, presumably nobody would care to watch it. So instead the movies invent their own political reality: an imaginary world in which larger-than-life figures engage in vast conspiracies, monumental betrayals, outrageous scandals and unbelievable conversions. These last are often based on the even more unbelievable dream of a world without politics, in which our public men — I suspect the thing wouldn’t work even as well as it does, which is not well at all, if you substituted women — act only from principle and with regard to nothing but the common weal. Such impossible goodness thus becomes the excuse for the impossible badness that precedes it in the well-worn character arc of the movie politician, which is repeated yet again in Jay Roach’s supposed satire, The Campaign.

Mr Roach’s Game Change, the TV movie about John McCain’s choice of Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, showed the extent to which his imagination is limited to media commonplaces about the political world that is otherwise beyond his ken. In Game Change it was the already well-established media trope of Mrs Palin’s supposed stupidity, which Game Change helped to establish even more firmly. In The Campaign it is the supposed wickedness of the Koch brothers, as well as the iniquity, devoutly affirmed by every lefty, of the Citizens United decision of the Supreme Court which has supposedly conferred on billionaires in general and the Kochs in particular enormous and illegitimate powers to influence elections. The name of the brothers here, as played by John Lithgow and Dan Ackroyd, is transformed from Koch (pronounced Coke) to Motch, and their evil plan is to “insource” Chinese workers — or at least Chinese working conditions and wages — to the bucolic North Carolina congressional district represented by their creature, Cam Brady (Will Ferrell).

Yeah, that sounds like something the Koch brothers must be working on. Their trouble in the movie, however, is that Cam, a Democrat, has what used to be called, back in Bill Clinton’s day, a “zipper problem,” so the Motches transfer their allegiance to a hand-picked Republican, the strange man-child Marty Huggins (Zach Galifianakis), who seems intended to be a sort of redneck version of Corky St. Clair, Christopher Guest’s provincial thespian in Waiting for Guffman, who doesn’t know he’s gay. That’s good for a few laughs, as is Cam’s manic philandering and blatant hypocrisies. He’s even more stupid than Julianne Moore’s (or Tina Fey’s) Sarah Palin, but Marty is rendered almost as idiotic himself by the exigencies of campaigning. The movie thus becomes yet another variation on the “Dumb and Dumber” cross-talk act wrapped up at last by yet another bogus conversion scenario in which it is the Motch brothers who are left with the pie in their face.

The film begins with an epigraph from Ross Perot: “There are rules in war; there are rules in mud-wrestling. There are no rules in politics.” But this is not true. The media just love the idea that it might be, but they very well know that it isn’t, since they themselves are in the business of enforcing the rules with their constant monitoring of politicians for potential scandal. Almost any of the things Cam Brady does, for instance, from getting caught drunk-driving to punching a baby to screwing his opponent’s wife and putting out a sex tape of the encounter would be under media rules more than enough to be an automatic disqualification for electoral office in the real world. It is only in the movies’ political fantasy world that Cam goes on and on committing ever more impolitic outrages against the media’s code of behavior. He is said in the beginning to have done what the real-life Democratic Congressman Anthony Weiner did, but he doesn’t suffer Mr Weiner’s political fate for it, nor yet that of Eliot Spitzer whose fate-worse-than-death has been to join the pack of media hyenas himself.

And yet the media insist that the movie is true to life! A.O. Scott of The New York Times writes that

there may be comfort in the thought that the American people would never elect clowns like these to any office. But then a glance at some of the clowns we do elect, perhaps especially to our national legislature, might lead you in the opposite direction. Really, the movie could not possibly go far enough unless the screenwriters (Chris Henchy and Shawn Harwell) had abandoned all invention and transcribed the script directly from C-SPAN. And so The Campaign wobbles between the vaguely topical and the completely preposterous.

Mr Scott is usually a thoughtful critic, but here he is clearly on auto-pilot. Lip service to the media view of political “clowns” — perhaps on the assumption that if there are no real life Cam Bradys in Congress it is only because they haven’t been discovered yet — is de rigeur. Variety’s critic writes that “Roach proceeds to illustrate just how flagrant things can get, and yet the humor works because everything connects back to the real world.” Of course, it’s not “the real world” but the media world — the world in which all congressmen are corrupt morons and billionaires routinely conspire to bring Chinese wage levels and environmental standards to the US — for which people are more and more frequently prone to mistake it. That they should continue to make that mistake is as much in the movies’ interest as it is in the media’s.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.