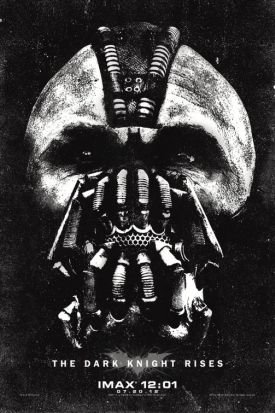

Dark Knight Rises, The

When I last reviewed one, I wrote that a film critic reviewing a James Bond movie inevitably feels like a food critic reviewing a McDonald’s Restaurant. In both cases there is really nothing to review, as the effort expended by the authors has not been to produce something new that, in their judgment, will please us but merely something that is as close as possible to what we already know pleases us. Thank you for not surprising! Even if it doesn’t please, the point is the same: to follow a formula in order to reproduce an experience that the same formula has produced in the past, whether we like the result or not, since the audience that likes it is a large and loyal one that keeps coming back for more of the same whatever those who don’t like it may do. And from the point of view of the franchisees, one of the advantages of ownership is that it short-circuits the critical process by reducing it to irrelevance. Every review will amount to this: for those who like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing they will like. Everybody already knows that anyway.

I think much the same is true of superhero movies. As someone who has been criticizing them for years after a long period of regarding them as a harmless indulgence and irony practice for the largely irony-free American film industry, I have now arrived at the point where the criticism seems as automatic as the movie formulae themselves. For one thing: no more irony. Criticism, I find, is dumbfounded by those who take such stuff seriously — as, hitherto, only children have been able to do. You have only my word to go on that each time I force myself to go to another one of these dire productions — and I don’t go to many anymore — I really do try to find something to like about it, something that can be taken seriously. But each time I find that the fantastical element, which is of the very essence of the superhero genre, so overwhelms anything that might in its absence have been a good idea that my optimistic impulses are crushed. The need to stick to the formula makes anything new or interesting extremely difficult, if not impossible.

This loss — and I do feel it as a loss — is the more to be regretted because it puts me at odds with the legion of younger critics who have grown up with these movies and seem to like them all the better for not treating their camp heroes as jokes anymore. What more natural than that they should think my not liking them merely a result of being old and out of touch, stuck in an era when, admittedly, almost nothing was taken seriously? Perhaps they are right. But even if they are, it doesn’t make it possible for me to regard the third and final movie in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, The Dark Knight Rises, as having anything more truthful or interesting to say than its two predecessors did. This must be all the more galling to my colleagues who do, at least the conservative ones, because there is something of a consensus that Mr Nolan has a conservative message for them, which they regard as reason enough for them to like it.

John Podhoretz of The Weekly Standard, for example, is at pains to distinguish this movie and its predecessor from the run of superhero movies, saying not only that “most of these movies are lousy” but that this is a fact about which “even diehard fans agree.” That is not my impression, but let’s say he’s right. Where, it seems to me, he cannot be right is when he claims that it is precisely by eschewing irony about super-heroism that The Dark Knight Rises triumphs. It “represents the true maturation of the superhero movie,” he writes in defiance of what seems to me the undeniable fact that it is of the very essence of the superhero movie, like the comic books on which it is based, to be immature by favoring fantasy over reality. Mr Podhoretz handsomely admits that all superheroes represent an “empowerment fantasy” for “young kids and teenagers who feel so powerless in their own lives,” but they are more than that. They also depend for their success on what we might call a disempowerment fantasy about the rest of the world.

In other words, for Batman and his adversaries to be super, everybody else has to be negative super, or sub-ordinary. This is the key point about the formula to which Mr Nolan is confined, like Batman (Christian Bale) himself, in his giant open garbage can of a dungeon but without even the Caped Crusader’s plainly fantastical prospects of escape. For the immature not only seek the imaginative means to feel implausibly strong themselves, they also seek confirmation of their belief in the implausible weakness or wickedness of pretty much everybody else. Mr Nolan’s Batman movies spend far more time and energy on promoting this vision of the world than they do on the superpowers of Batman and his Bat-machines which stand out against it. The masses in Mr Nolan’s account are corrupt and cowardly: good when untroubled by evil-doers but quickly yielding to the bad (or simply seeking to escape it) when evil-doers gain power, as they periodically do. Batman’s appeal is based not just on the uniqueness of his strength and ingenuity and fighting prowess but on his moral solitariness. Unselfish and courageous, he’s really the only one in his world who is. His example may inspire Catwoman (Anne Hathaway) and a guy (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) who turns out — spoiler alert! — to be auditioning for the part of Robin, but as Commissioner Gordon (Gary Oldman) points out, there’s no one but he who can save Gotham.

|

Conservatives used not to believe people were in need of that kind of saving. Conservatives, at least of the American variety, used to have faith in the people to save themselves. Their heroes were not of the Super- variety but regular guys like Gary Cooper’s Sergeant York or John Wayne’s Sergeant Stryker in The Sands of Iwo Jima, guys whose rising to the occasion inspired others to do likewise but who didn’t give themselves airs — let alone run around in a mask and a rubber suit and the coolest vehicles in town. Mr Podhoretz’s Weekly Standard colleague Jonathan V. Last is of one mind with him in claiming that “Batman is different” from the other superheroes in having a genuine claim to be treated philosophically.

He is not an avatar for a particular political argument or idea. Batman is about the liberal order itself — specifically about the durability of classical liberalism in the face of modernity. From the beginning, Batman concerned himself with justice. Whereas Superman spent the 1930s and ’40s fighting for the common man against powerful interests — corrupt industrialists, scheming munitions manufacturers, dirty bankers — Batman fought mobsters. If you look at the original Batman comics, he’s forever chasing gangsters and colorful criminals, such as the Joker. Sometimes he’d arrest the evildoers; sometimes, if they were particularly repugnant, he’d kill them. In later years he evolved and swore never to take a life.

One might agree with his contention that the movies — for he, too, celebrates both this one and the previous one in the series — promote a conservative vision of the contemporary world if they presented anything even remotely similar to the contemporary world. They don’t. Like the classical heroic literature of which they are a parody, they depend utterly on creating a special (super-) heroic world of their own, remote from everyday experience, wherein such amazing deeds as they present for our inspection may be believed actually to have happened.

Comic books and their superheroes are also like heroic literature in this, that they imagine their greatest figures as lonely men, standing far above the run of mankind to which their powers make them superior. For the Greek heroes Achilles or Odysseus, this was enough. The proto-Roman Trojan Aeneas introduced the idea of a moral superiority to match the physical, though this superiority was based on what Virgil calls “piety” and not what we think of as moral or ethical behavior. The lone heroes of today are also seen as saviors of the good, but where they differ is in the comics’ penchant for building up their heroes by tearing down those around them. As the only unsullied hero in a world of evil-doing, cowardice and corruption, Batman naturally shares the adolescent penchant for brooding. He broods not only over the death of his parents, which turns him into Batman in the first place, but also over his inability to escape being Batman and thus someone alone and untouchable in a world of his manifest inferiors.

In The Dark Knight his brooding in the prison of himself took the form of a pseudo moral quandary in which he could not but see himself as equaled only by the supercriminal he opposes, so that the duel between them became a mere spectator sport for the rest of the world — or that part of it which managed to escape being among the Joker’s victims. Like Batman’s priggish and nonsensical refusal to use firearms (apart from those mounted on his mega-cool Bat-vehicles), this clash of the titans was meant to appeal to those who are still capable of thinking they might be too good to live in this naughty world with all its shameful hypocrisies. That’s the same way the teenager looks with scorn on the adult world: because he is afraid of having to join it. In The Dark Knight Rises, Batman broods over his inability to fit in romantically, as well as his being misunderstood by the world as a bad guy himself. The adult way out of both these emotional dead-ends is to say: Get over yourself! Get real! We know that that is not how the world is, not even for the super-est of superheroes. But reality is not an option for the irony-free superhero movie.

|

The conservative virtues that some say are celebrated by these films are not, whatever else they may be, solitary ones, any more than they can include the idea of “a one-man department of justice,” to cite the title of Mr Last’s piece. They depend for their coherence on a belief not just in virtuous individuals but a virtuous people. That’s also why it is a mistake to claim, as Jonathan Last does, that “the Joker is the kind of foreign, illiberal threat that al Qaeda presented to the West.” No he’s not. Al Qaeda doesn’t want to “watch the world burn” as the Joker is said to do. For all the horrible deeds Islamicist extremists commit, they have a positive, rational aim in view in the worldwide triumph of Islam which, however repugnant it may be to us, is not merely nihilistic, like that of the Batman villains, and nor does it even remotely threaten a total breakdown of civil order and decency, as it does in The Dark Knight Rises. The idea that Occupy Wall Street might do so is as much a fantasy as anything in the picture. The paranoia that sees such threats in the real world is more associated with the left than with the conservatism that well-intentioned apologists are trying to attribute to Christopher Nolan.

There are all kinds of ways in which Americans of today may be supposed not to measure up to the sturdy republican virtues of their fore-fathers, but it’s ridiculous to find any resemblance at all to the mere mob they have become in Mr Nolan’s eyes. That image is simply the complement of the lonely Batman-hero. His moral isolation is what is being celebrated, and it depends on the immorality or amorality of those around him, both of which things are adolescent fantasies and nothing to do with real-world politics or those who engage in them. But the media have been promoting this dream of their own purity in the midst of a corrupt and vicious political world since Watergate, and the movies have gone along with it, pari passu, ever since, cranking out fantasies to that effect both acknowledged, like the Dark Knight ones, and unacknowledged, like All the President’s Men (1976) — a movie whose central idea of massive corruption at the heart of power opposed only by one or two lonely outsiders is still going strong in, say, the latest Bourne picture, which is nothing but yet more superhero fare thinly disguised.

For those who like such things, as I have foretold you, The Dark Knight Rises is the sort of thing they will like. But then you knew that anyway. I very much regret being Batman-lonely myself in feeling obliged to correct their taste — so much so, indeed, that I am more than half doubtful that I should even attempt to do so. I am certainly under no illusions that I can peel off any of the movie’s millions of fans, let alone a significant number of them. When criticism has become irrelevant, perhaps it is time for the critic to shut up. If I have not yet done so, it is only because I think there is some value in reminding people that the culture once offered up something better and more wholesome to the popular appetite for excitement and moral models — and that, if we ever weary of that which we have got instead, it might do so again.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.