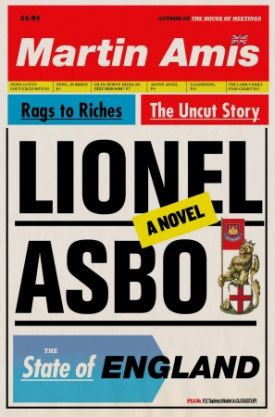

Lionel Asbo

From The Washington TimesLIONEL ASBO: STATE OF ENGLAND

By Martin Amis

Alfred A. Knopf, $25.95, 255 pages

The London Daily Telegraph recently published an article about how Adrian and Gillian Bayford of Haverhill, Suffolk, winners of $233.7 million in the lottery, “showed the money hasn’t gone to their heads” by taking their first overseas family holiday on the cut-rate airline easyJet. The story suggests that the lottery nowadays, at least in Britain, may owe its popularity as much to the chance of instant celebrity as to that of instant wealth. The Bayfords, at any rate, seem instinctively to have recognized that restraint makes for better publicity than vulgar ostentation.

Martin Amis could learn something from their media savvy. His new novel, Lionel Asbo, about a man who wins $221 million in the lottery, comes with a dust jacket done in tabloid newspaper style, with the author’s name as the media brand and the title as the splash headline. The subtitle, “State of England,” stands for the story. But Lionel Asbo is not about the state of England. It’s about the state of England’s media. In this sense, you can tell the book by its cover. Mr. Amis is as keen as any tabloid editor could be for a story like that of his eponymous hero, nee Lionel Pepperdine of the fictional and impossibly crime-ridden London borough of Diston. The trouble is that there are no stories like it.

Lionel’s fictitiousness is his most salient characteristic. He supposedly has changed his surname to the popular form of the now-discontinued Anti-Social Behavior Orders introduced by Tony Blair’s Labor government. Instead of curbing juvenile crime, the ASBO became a badge of honor, as it presumably was to Lionel at some point after he supposedly was served with his first one at age three and before becoming a full-blown criminal as a preteen. I guess if you are prepared to suspend disbelief to that extent, you will find it easy to believe that an unrepentant and grown-up criminal like Lionel should take pride in identifying himself with a mere public-disorder offense. But the impossibility of any real-life Lionel is the point of him. He has no existence apart from that of the tabloid “Lotto Lout.”

One supposes he was created to serve the dubiously ironic purpose of mocking the media’s sensationalism, but, like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, the novel soon fi itself unable to distinguish between its satire and what it supposedly is satirizing. Hence the confusion over the “State of England.” Insofar as Mr. Amis is able to keep his gusty hyperbole on an even keel, it is because of the character of Desmond Pepperdine, Lionel’s orphaned, mixed-race nephew, who regards him as an “anti-dad or counterfather,” but with affection nonetheless. Desmond, who has inexplicably middle-class longings to go to the university, become a journalist, marry and have children, is the novel’s reality principle, but that only makes his loyalty to Lionel, whose sole avowed principle is “Never learn,” seem as unlikely as Lionel himself.

The novel’s characteristically energetic prose gives it an initial burst of readability, but as there is little more to it as story than the serial misadventures of a proudly uncouth thug who suddenly finds himself in possession of fabulous wealth, its forward momentum begins to sag well before the halfway mark. The one bit of suspense that keeps it going is the expectation of a terrible vengeance to be visited on Desmond by Lionel if and when the latter discovers that, at age 15, the former was seduced by his own grandmother, Lionel’s mother. Aged 39 at the time, as both she and her daughter first gave birth at age 12, Granny is 45 and already senile with what Lionel calls “that German lurgy that rots you brain” (Alzheimer’s disease). She keeps offering up hints of her dark secret in the form of cryptic crossword clues.

More implausibility, sure, but also a reminder of the extent to which Mr. Amis‘ writing is, as always, steeped in his Englishness. On almost every page, he expresses his delight in distinctively British wordplay, in Dickensian allusions and place names and the picturesque slang of the grotesques from the lower orders. His obsession with Lionel’s accent and social attitudes is also very British and reveals a shy conviction that his hero, in spite of his absurdity, really is typical of the British underclass. This makes his book something of an ironic commentary on Mr. Amis‘ recent and much publicized removal from Albion’s shores to Brooklyn’s — though it is likely to strike his American readers as a bit of a yawn. Like those of the Telegraph, a newspaper he satirizes as declining into tabloidization, they might take more of an interest in the Bayfords’ touching frugality than in the frankly unbelievable doings of Lotto Lout Lionel, whom the media’s endless sensationalizing of social pathologies has made, paradoxically but sadly, all too predictable.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.