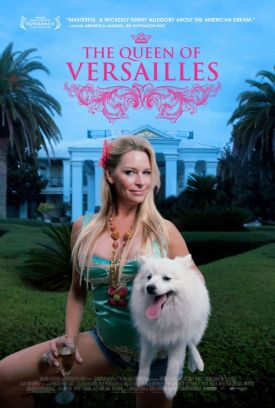

Queen of Versailles, The

“That’s it baby, when you’ve got it, flaunt it! Flaunt it!” So says Zero Mostel’s Max Bialystock in Mel Brooks’s The Producers (1968). The sentiment, though not unprecedented, was not characteristic of the rich in America theretofore. Old money here was nowhere near so old as old money in Europe, but it had something of the same disdain for vulgar ostentation. Like so many other traditional beliefs and attitudes, that one was on its way out by the end of the go-go Sixties when The Producers was made, but this has never prevented artists, writers and film-makers from affecting a similar attitude of cultural superiority to those they characterize as the latter-day nouveau riche, often for political reasons. I take it that some such impulse lay behind Lauren Greenfield’s Queen of Versailles, a documentary about a Florida billionaire named David Siegel and his trophy wife, Jackie, who were building what was to be, at 90,000 square feet, the largest private home in America before the crash of 2008 more or less wiped out Mr Siegel’s time-share empire.

But in the course of patronizing and making fun of this couple and their brood of spoiled children, Ms Greenfield must have been surprised to discover that the precipitous decline in their fortunes had made her subjects almost sympathetic — and her movie is all the better for it. It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good, they say, and Mr Siegel’s misfortune at least had the benefit of making Queen of Versailles into something more interesting than it would have been as the mere act of humorous condescension that the footage shot before the good times ended suggests it was intended to be. Jackie, in particular, with her pneumatic chest and shopaholic ways, is transformed from a figure of fun into one of pathos. But condescension is built into this kind of movie, which is what makes the sympathy, when it comes a surprise — and something against the grain of the medium. Not quite transformed into Schadenfreude, it lingers in the air as a modern-day “Vanity of Human Wishes” might do, if one could imagine such a thing in our politicized age.

Unfortunately, the critical reaction to the movie shows how poorly equipped we are nowadays to think otherwise than politically about such subjects as Queen of Versailles raises — mostly inadvertently, it must be said, since the authors are also prisoners of politics. At our first introduction to David Siegel, for example, Ms Greenfield shows him arrogantly asking himself, “Why did I build the biggest house in America? Because I could.” Then, with a nudge and a wink he tells her about how he was supposedly responsible for the election of George W. Bush in 2000, though he would rather not say how, since what he did was “not necessarily legal.” That has him placed all right. Maybe it’s also what led Justin Chang of Variety to write of: “Lauren Greenfield’s often hilarious, mostly infuriating chronicle of the rise and fall of one of America’s most obscenely wealthy families.” It’s hard to think of what else he might have found infuriating or obscene about poor Mr Siegel’s misfortune.

Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post writes that “it would be so easy to demonize Jackie Siegel” — easy for her, I suppose — “but by the end of the film, with the animals dying, her house descending into unkempt chaos and her marriage fraying, viewers can’t help but feel confounded sympathy for a woman who so willingly bought into the American Dream at its most perversely distorted. Attention must be paid, even to those who so outlandishly overspent.” Ms Hornaday’s glib use of “American Dream” together with “perversely distorted” doubles the irony of her criticism back on her. She doesn’t see that “the American Dream,” at least journalistically, is never used except ironically anymore, and it’s already been “perversely distorted” out of all recognition when applied to a Louis XIV-scale palace that can hardly be identified as distinctively American.

But to me what is most striking thing about the movie is how those from whom one might least expect it stick by the stricken mogul. His son by an earlier marriage who has day-to-day running of the business tells the camera early on, during the high volume days on the sales floor, that he and his father are “not close” and have what is essentially “a business relationship.” Yet when all his other business associates have deserted him, he insists he is sticking by his dad. Jackie, too, though she shyly admits to being rather pleased that David has been to a degree “humbled’ by his troubles — not humbled enough, some will say — likewise insists that she is in it for the long haul, no matter what happens. Looking on the bright side of life, she says that the “stress has made us closer, stronger. . . [It’s true] what they say, when you’re down, you find out who your friends are.”

David, however, has not been so blessed in his troubles. So devastated is he by his losses that he tells Ms Greenfield’s camera: “Nothing makes me happy these days; I will be happy when I find a solution to — ” and he looks around him — “This.” The key moment in the film comes when David is asked, “Do you get strength from your marriage?”

He hesitates a moment and then replies: “No. It’s like having another child.” But, of course, that’s what he chose Jackie for. Their romance must have been a bit like Max Bialystock’s telling Leo Bloom: “I’m going to buy a toy. I worked very, very hard and I think I deserve a toy.” The “toy” is of course Ulla, played by Lee Meredith, the receptionist who can’t speak English and whom Max describes as “an adult, educational toy made in Sweden for children over fifty.” Ulla bears more than a passing resemblance to Jackie Siegel, who gives a whole new meaning to the expression, her face (sc. other body part) is her fortune. It’s all desperately sad — unless, I suppose, you have your politics to comfort you.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.