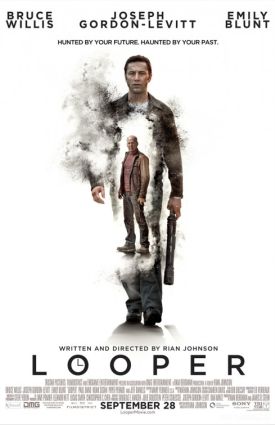

Looper

One measure of the extent to which culture is undermined by unbridled recourse to fantasy lies in how blasé we have grown even about the most amazing ideas fantasy has to offer. In Looper by Rian Johnson, for instance, the once mind-expanding concept of time-travel has been caught and contained within a narrative framework so narrow that the remarkable notion of a loophole in the time-space continuum through which people might voyage between past and future becomes nothing more than a means for unseen criminals of the future to dispose of the corpses of their murder victims. These are sent alive from the year 2074, trussed up and hooded with bars of silver strapped to their backs as their assassins’ fee, thirty years into the past where the likes of Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) are waiting for them with a scatter-gun. All Joe has to do is pull the trigger and collect his silver.

The conceit of Mr Johnson’s story is so far out of proportion to the time-travel concept that the latter is merely ridiculous. That may of course be deliberate — an excuse for the nudge-nudge, wink-wink postmodernism that disfigures this movie as it did the author’s earlier Brick (2006), which also starred Mr Gordon-Levitt as a high-school age noir-style detective. Here, the plot is set in motion because Joe and his brother assassins, or loopers, are starting to find that among their victims are their future selves, their usefulness to the crime lords of the future presumably exhausted, on whom they are expected to “close the loop.” The hoods worn by the murderees are thus useful in disguising from the murderers the moment at which they are expected to confront, and kill, their future selves.

At least their doing so doesn’t present any logical or metaphysical problems of the sort that arise when the tables are turned and Joe’s future self, played by Bruce Willis, arrives without a hood and with the intention of using Joe’s moment of hesitation on seeing before him an older Joe to escape his fate — and, having escaped it, to kill the little boy who he knows will grow up to be the man who will kill his wife (Summer Qing) in the future. Old Joe is under a certain disadvantage vis a vis his younger self, whom he must obviously avoid killing lest he also kill himself. Young Joe, by contrast, has no tender or sentimental feelings about Old Joe and would be determined to do his job by killing him even if he weren’t being chased by yet more assassins on account of his failure to do so. “Why don’t you do what old men do and die?” he says in a slightly comic confabulation between the two in a diner that doesn’t look the least bit futuristic. Perhaps diners never do.

But things begin to get a bit more interesting when Young Joe, on the run, is the first to stumble upon the future wife-killer, a proleptically legendary crime lord called the Rainmaker, who turns out to be a strange little boy named Cid (Pierce Gagnon) with telekinetic powers, living in an isolated Kansas farm house with his super hot and super lonely single mother, Sara (Emily Blunt). As Joe has not yet met the future wife over whom his future self is to display such solicitude, Young Joe and Sara obviously make a couple after their meet-cute at the business end of Sara’s shotgun. Young Joe recognizes at once that she is too tender-hearted to shoot him, even if she weren’t super attracted to him, and soon he has become the man of the house and the protector of Sara and her boy, as well as himself, from the would-be killers of both present and future.

Bearing out the conventional wisdom about how people tend to be conservative in old age after a more liberal youth, Old Joe is an advocate of stern if premature justice and determined to kill the kid while Young Joe is a bleeding heart believer in what we might call prehabilitation. In other words, he thinks that if Cid’s mommy somehow manages to survive and bring him up in a loving home instead of becoming the collateral damage of the would-be assassin’s bullets intended for her son, as seems to be her destiny in one of the possible futures that the film maps out, the kid may willingly change the course that destiny has apparently laid down for him, too. That is, he might not become the Rainmaker after all — or at least not the Rainmaker who goes around killing people’s wives. Perhaps with his tele-kinetic powers he will become a real rainmaker instead. Or a TV magician.

The tele-kinesis bit seems to me a superpower too far. The trick of making fantasy seem at least a little bit real is to surround it with enough real stuff that unreality gets lost in the shuffle, not to multiply unrealities. But I get the impression that making things look real is not a real big part of Rian Johnson’s purpose in making Looper. Reality must seem to him irrelevant to the moral, or quasi-political, point he does want to make. As his sympathies obviously lie more with liberal Young Joe than with conservative Old Joe, he contrives a clever if not entirely satisfying ending by which, it may be hoped, a spirit of goodness and self-sacrifice will put an end to the cycle of violence before it begins and so turn the future into something quite different from that which this movie, like so many “dystopian” visions of that elusive eventuality, assumes will be dreadfully grim and violent. Well, we know that grimness and violence are what is expected of the movies, as well as of the future, but there would hardly be any point to stories of time travel if they didn’t allow us to indulge ourselves in the fantasy that things might yet be different.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.