Enter Alternative Reality

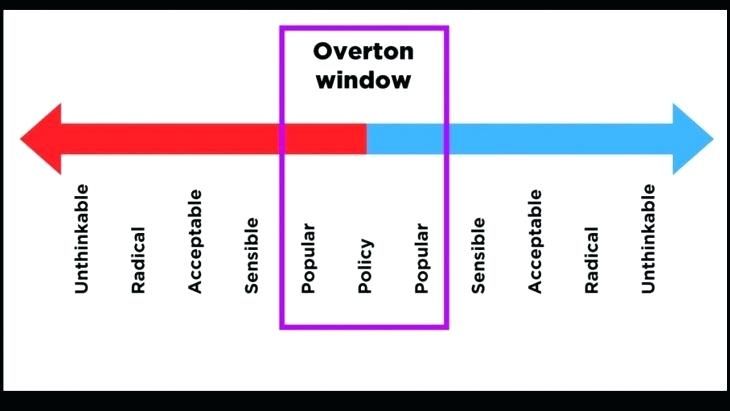

From The American SpectatorWriting a month before the November election, I won’t hazard any guesses as to how it comes out, but I will predict that one expression which survives the campaign, along with (unfortunately) “the 47 per cent,” will be Bill Clinton’s “alternative universe — possibly modified to “alternative reality.” He was speaking, as you may remember, at the Democratic convention in Charlotte about what he insisted, not entirely without reason, was a Republican caricature of the Democrats as people who “don’t really believe in free enterprise and individual initiative [and] want everybody to be dependent on the government.” I don’t mind telling you that his words made me sit up and take notice. Could it be that old Slick Willie was calling on both sides for rhetorical disarmament in the ever more surreal war of hyperbole that American election campaigns have become? Alas, no. For he then proceeded to create, without any apparent sense of irony, an exactly complementary caricature of Republicans as people who believe that “every one of us in this room who amounts to anything, we’re all completely self- made.”

In reality, if I may borrow an old-fashioned term, he was bestowing a sort of official recognition on the rhetorical status quo, in which all realities are alternative — alternative, that is, to the real kind. It’s only what we might have expected from our 42nd president, who was the founder and formerly chief practitioner of postmodern politics. The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan is supposed to have said that “You’re entitled to your own opinions; you’re not entitled to your own facts.” That is Oldthink. Now, you’re entitled to your own facts, and that has had the curious effect of making opinion obsolete. Thus the so-called “Fact Checkers” of the media routinely treat opinion as fact — most often in the course of dismissing opinions they don’t like or agree with as contrary to fact, or lies — and that, in turn, has gone far to make actual lies, licensed by the presumed right of everyone to construct his own reality, the common currency of the campaign, particularly on the Democratic side.

Not to open a whole new campaign of my own in my ongoing war against fantasy, but isn’t this regrettable state of affairs more or less what we would expect from people steeped in the popular culture of the last thirty or forty years? Culture is upstream of politics, as someone has said, and alternative realities of the political sort follow naturally from those in fiction, theatre and movies which, having proliferated like crabgrass, are now at the point where they have taken over the cultural lawn. Even if some brave author were to come forward with an attempt to re-establish the link between art and the reality of which it was once supposed to be imitative, the world would treat his portrait of reality as just another alternative version of it, like all the rest. Movies have led the way to the breeding grounds of fantasy and are now virtually all examples of it.

I find it amusing that criticism of a movie like Rian Johnson’s Looper, which is about time-travel between two equally repellent futures, centers on how nearly Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s prosthetic nose has been made to resemble the real one of Bruce Willis, who plays his future self, a retired assassin named Joe. The two men may or may not be plausibly time-altered versions of each other, but there is nothing at all plausible about the characters they play or the worlds they inhabit. Plausibility of that sort is no longer expected or even wanted in postmodern movies, of which Looper is a good example. When the critics finished commenting on Mr Gordon-Levitt’s nose, they went on in learned fashion to cite as many as they could of the picture’s allusions to other movies. Movie-world is now its own alternative reality, and comparisons between films of the same general type have taken the place of comparisons between any of them and non-filmic reality.

The plot of Looper is far too complicated to go into detail about, but a crucial element of it plays with our expectations about the central hypothetical of an older man somehow permitted to return to the past and give the benefit of his knowledge and experience to his younger self. At one point, future-Joe actually says to present-Joe: “Don’t do it, you idiot” — though he is presumably able to remember that he has already done it. Yet which of us has not engaged in similar futility? It almost looks as if the movie is going to make a realistically human point about our ability, or inability, to learn from experience — perhaps a comic one like that of a great Czech time-travel movie of the Cold War era called Tomorrow I’ll Be Scalding Myself with Tea that only showed once on Western TV, on the BBC in 1982, and is remembered by its fans (of whom I am one) on that occasion like a form of time-travel itself. But Looper’s human moment turns out to be a po-mo tease and a red herring to distract us from the surprise ending, which depends for its surprise on its unrealism.

No, I take that back. Anyone familiar with the conventions of the “dystopian” cinema that I discussed in these pages a few months back (see “Look Back in Hunger” in The American Spectator of May, 2012) and that Looper is obviously intended to be a part of might well see the ending coming, though I confess I did not. It may be implausible — to say the least — from the point of view of those of us whose tastes were formed by old-fashioned realism, but it makes perfect sense within the terms of the alternative reality which is a collaborative product of our movie fantasists. That reality is not merely idiosyncratic, in other words, but part of a shared vision among mostly left-wing writers and film-makers of a nightmare world in which evil, as we of the non- or pre-alternative reality would term it, has become the norm.

This world, in spite of their fantastical style, these writers and film-makers really do imagine to have important points of contact with the world they live in, a world in which (as they suppose) the fantastical evil of the One Percent is thought to blight the existence of the ninety and nine per cent who are less fortunate — or perhaps only less evil. Although the third of Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies, The Dark Knight Rises, which dominated the summer box office was thought by some to have a conservative take on this alternative reality — perhaps because benevolent billionaire Bruce Wayne could hardly escape his fate as a congenital member of the One Percent — it is still the same world. The pessimism with which evil is supposed to render the good and the decent so helpless that only superheroic intervention can save them is only heightened by the patent unreality of such intervention.

There are obvious similarities between this lefty fantasy of evil predominant and that which has been purpose-built for the presidential campaign: an alternative reality in which Mitt Romney is portrayed as a dangerous “extremist,” one of the evil rich keeping the rest of us down, and one who is also bent on waging a “War against women” by taking away their birth control devices. Those of us who do not share it find it almost impossible to accept that the Obama campaign really believes in this fantasy, but the fantastical quality of the popular culture has accustomed them, almost without their being aware of it, to believe similar things. Such is the power of the mimetic assumption, inherited from 3000 years of Western culture — the assumption that art is an imitation of reality — that even when we create avowed fantasy, we can’t help ourselves from seeing it as, somehow or other, analogous to reality. In such cases, however, it is reality which must adapt itself to the fantasy. That’s how it becomes “alternative.”

|

The habits of fantasy tend to run in familiar grooves, which also helps them to bend and shape our ideas of reality. I have no more wish to read J.K. Rowling’s new adult novel, A Casual Vacancy, than I did her twee Harry Potter tales, but judging from accounts of it that I have read I guess some similar urge caused her to write what one critic describes as “500 pages of swearing, rape, drug abuse, suicide, drowning, self-harm, pseudonymous internet denunciations, domestic violence, acne and meetings of the parish council. . . After more than a million words of Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling has contracted Tourette’s Syndrome.” It sounds to me as if she has merely escaped from one sort of fantasy into another, and both sorts were already there, waiting for her to exploit them — the Harry Potter sort in the largely unfamiliar (to Americans) British school stories of a generation or two ago and the Casual Vacancy sort in the pessimistic world-view of so many contemporary fictional and cinematic productions that we don’t even recognize it as a fantasy anymore. But the great liberating effect of post-modernism, first in culture and then in politics, is to make us care no longer whether it is a fantasy or not.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.