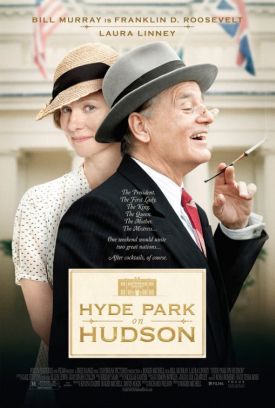

Hyde Park on Hudson

That Roger Michell’s and Richard Nelson’s Hyde Park On Hudson opened on December 7th could be said to add a new dimension of meaning to Franklin Roosevelt’s dictum after Pearl Harbor that it was “a date that would live in infamy.” Certainly, he would not have been pleased by the film’s portrait of himself — assuming it were possible (as, of course, it wasn’t) that any such film could have been made in his lifetime. Yet in our 21st century world it will doubtless come across to many as an effort to “humanize” the great man — who will, accordingly, shed some of the characteristics of historical greatness and take on some of those of the celebrity, that new thing in the world which, since Roosevelt’s time, we have learned to desiderate in our presidents and even in lesser politicians. FDR’s “star power” or “charisma” can only be retrospectively enhanced by this movie — though it is, as I say, more than doubtful that he himself would have valued any such commodities.

The movie is, as Mark Tooley has pointed out on the American Spectator’s website, a “tall tale” which imagines the aristocratic FDR’s behaving more like such low-life successors as Jack Kennedy and Bill Clinton than there is any historical warrant for believing he actually did. Yet I would disagree with Mr Tooley’s characterization of the movie as “trash.” Trash is, in any case, today’s cultural currency. There is scarcely anyone now left alive who knew Roosevelt the man, so that if he is not yet he soon will be as much a subject for literary reinterpretation as the Plantagenet kings of England were by Shakespeare’s time, a century after the last of them had died. Shakespeare’s kings were probably as much at variance with their historical counterparts as Mr Michell’s FDR, but we may find an unexpected delight in what his picture has to say about the meaning and desirability of the celebrity culture which, as some of us believe, has had such a lamentable effect on our politics since Roosevelt’s time.

The first and most important thing it has to say about this culture has to do with its ultimate derivation from traditional views of royalty. The movie is set at Hyde Park, FDR’s mother’s home (as it then was) in New York state where, in the summer of 1939, the President (Bill Murray) is visited by the British King, George VI (Sam West), and Queen Elizabeth, later to be known as Queen Mum (Olivia Colman), just as the Second World War was looking to more or less everyone to be more or less inevitable. The importance of the visit, the first by a British king to these shores since the Revolution, as a good will exercise in winning America’s help for his country in the coming war against Nazi Germany is stressed throughout, as is the king’s doubtfulness about his own ability to accomplish his mission — or much of anything else. Both things seem to have been historically accurate, as is the king’s stutter, which we learned all about two years ago from the Oscar-winning King’s Speech.

At the time of the visit, it had been less than three years since the king had succeeded his brother, Edward VIII, subsequently Duke of Windsor, who had been forced to abdicate in order to marry, as he put it, the woman he loved, an American divorcée named Wallis Simpson. The glamorous Prince of Wales, as he was for more than two decades before briefly ascending the throne on the death of George V, Edward VIII had been one of the pioneers of the celebrity culture, and there can be little doubt that his attitude to the traditional stuff of tragedy — a Racinean conflict in great men between love and duty, which must always be resolved in favor of duty — had been affected by the popular preference for comedy and the triumph of love. Yet it also must have helped to assure that his brother’s reign, like that of the present monarch, his daughter, should have been characterized by the most proper sort of middle-class decorum.

Certainly Hyde Park on Hudson plays off of this irony by contrasting the comparatively prim royal couple with the sort of sexual shenanigans in the Roosevelt ménage that might have been expected from the old-fashioned sort of king, like Charles II or Louis XIV. In the Roosevelt household, the President is “serv’d, approach’d and address’d to with the most humble Submission, and superlative Respect,” as Bernard Mandeville says George I was more than two centuries earlier, and every courtier “was only born to procure him either Ease or Pleasure.” Roosevelt also represents an extreme of aristocratic endogamy by picking not only his wife, Eleanor (Olivia Williams), but his latest paramour — a distant cousin named Daisy Suckley (Laura Linney) — from within the family. When Daisy makes a reference to the last king’s having given up the throne for the woman he loved, Eleanor scoffs loudly: “Have you ever met a man who would do that?” Certainly she has been left with no illusions about the bourgeois ideal of conjugal love.

Most critics in America seem to have been more or less of Mark Tooley’s mind, in spite of a few raves. Peter Debruge of Variety uses the words “unseemly” and “tacky” in the first paragraph of his review, which just goes to show that if there is no one else whose dignity, we think, we are bound to respect, FDR’s still qualifies. As I remarked in my review of Your Sister’s Sister last summer, I didn’t think the word “unseemly” was even a part of the critical vocabulary anymore. Certainly it is not known to and would not have been understood by the characters in that movie. Mr Debruge sees it as a black mark against this one that “Nelson’s script constantly feels the need to reiterate the notion that presidents and kings really aren’t that special.” Pardon me for noticing, but didn’t the media figure that out for us a generation or more ago? But he also sees the centrality of the scene in the President’s study, over the whisky late at night

Hoisting himself out of his wheelchair, Roosevelt crosses the room to his desk, coaching the insecure young king on the fact that their subjects look past their leaders’ flaws and see only the strengths. “Can you imagine the disappointment when they find out what we really are?” he asks pointedly.

It’s a key moment, however, because of the historical context. Viewed from the perspective of a time when all — or nearly all — has been found out, the scene prompts the reflection that “disappointment” is not quite the right word to describe our insatiably prurient interest in what we find. We might also wonder if there isn’t something to be said for a culture in which the “flaws” of our leaders, like the President’s paralysis from polio, were deliberately overlooked as something unworthy of notice in someone ranking, as some people did in those days, well above celebrity level. Perhaps we should see the unseemliness of FDR’s apocryphal sexual adventures as part of a deliberate attempt to remind us of the existence of things that we once were and might once again be above wanting to know about.

Such ironies also give an extra level of meaning to the climactic scene in the movie when the King and Queen are served hot dogs at a Rooseveltian picnic. At first inclined to see this as a calculated slight, they realize only at the moment when the King takes a bite and the flash-bulbs of the assembled press corps start popping that Roosevelt has shown them the way to become modern monarchs, “humanized” (as FDR himself is according to our present decadent standards by his sexually predatory behavior) by sharing the fare of the common people. The common people in the movie cheer because they cannot yet see where such an apparently innocuous entrée into the celebrity culture will end — that is with Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress and cigars put to profane uses in the Oval Office. Knowing better ourselves, we can only be touched by the fatal innocence of the time and thus impressed with a historical truth that goes well beyond the merely factual.

Hyde Park on Hudson

is ultimately too slight a thing to win the coveted Bowman Two Stars, but what it does it does very well. The movie brings us not only Bill Murray as FDR but FDR as Bill Murray and, given the subject matter and the careful purging from the story of all but the most anodyne and uncontroversial sort of politics — most people, I fancy, will approve of Roosevelt’s tilt towards the British in the coming war against Hitler’s Germany — both are entirely convincing. As celebrity, at any rate, which, with the benefit of hindsight, we can imagine FDR’s being, the president fits the Bill Murray persona and vice versa. FDR’s being carried around by a muscular assistant while everybody pretends not to notice is just the sort of thing that we can imagine Mr Murray’s doing. But the removal of politics also has its own appropriateness on account its subject’s being FDR’s own attempt to escape from politics. Daisy says during the early days of their affair: “I believed I helped him forget the world — as if we had just run away.”

Laura Linney as Daisy may be the only actress I know of who can play plain or dowdy women without being in the least plain or dowdy herself. In other words, her sexual magnetism shines through no matter how much the part calls it into question or depends on a backstory involving her loneliness or unattractiveness. When, in Breach (2007) she says to Ryan Phillippe’s character that she is no good as a relationship counselor — “I don’t even have a cat” — we can believe, for a moment at any rate, that this luminous beauty could be so utterly alone. We can even believe that the best she can do in You Can Count on Me (2001) is a sleazy extra-marital affair with the even sleazier Matthew Broderick. Poor Daisy Suckley only died in 1991, at the age of 99, and surely doesn’t deserve the Lewinsky-like portrayal she gets in this movie. But I hope that, if she is looking down on it from among the other ranks in celebrity heaven, she will think it some compensation that she is being played on the celebrity-making big screen by such a paragon of modern womanhood as Miss Linney.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.