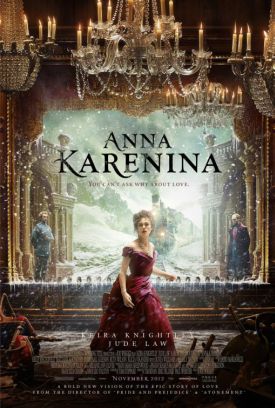

Anna Karenina

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?

Reply, reply.

It is engend’red in the eyes,

With gazing fed, and fancy dies

In the cradle, where it lies.

Let us all ring fancy’s knell;

I’ll begin it. Ding, dong, bell.

The Joe Wright-Tom Stoppard production of Anna Karenina certainly agrees with Shakespeare’s opinion, in The Merchant of Venice, about where sexual passion comes from. “Fancy” in the sense of sexual longing — still the word’s most common semantic association in the United Kingdom — is indeed bred in the eyes, both those of the characters and those of the audience. Accordingly, the film-makers offer us a visual feast of glittering surfaces to match the beauty of the actors playing its adulterous lovers, poor doomed Anna (Keira Knightley) and her ardent Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). Perhaps by way of further stressing the superficiality as well as the fatal allure of this surfeit of beauty, they also set the whole drama in a theatre whose painted backdrops and backstage machinery are placed periodically on view, before dissolving into more realistic settings, in order to complement the highly-wrought artifice both of the 19th century Russian social context and, more surprisingly, the passion that beats itself to death against its constraints.

The effect is further enhanced by sumptuous costumes and interiors and a discontinuous narrative that comes across more as a series of tableaux vivants than a conventional movie. Operatic emotion is given a quasi-operatic setting, but without the music — or with Dario Marianelli’s more movieish score in its place. The result of all this stylization is to drain some of the passion from Tolstoy’s story and its traditional sort of screen adaptation and so to repel and defeat our natural desire to identify ourselves with Anna. As she cannot resist being swept away by feelings, so we cannot not resist, in this context of artifice and theatricality, and must therefore look on her with something more of Tolstoy’s moral perspective than is commonly the case with adaptations of his novel. The movie’s justification must therefore be that it brings something new to the franchise, and something more in keeping with the spirit of the original.

Some critics have found it boring for this reason, but they should consider the possibility that their palates are too jaded by emotional excess to be pleased by the sort of moral drama that we associate with Shakespeare or Jane Austen. Yet this Anna Karenina isn’t like either of those authors either. It’s more a masque than a play — let alone a movie — and so might be better compared to Milton’s Comus, a celebration of sexual continence which has something of the same exultation in finding a moral template to fit on nature, though without the complementary tragedy of the woman who has thrown away her moral compass. Tolstoy’s undoubted sympathy for his tragic heroine tends to run away with the story as it is told today; this is a reminder that moderation of compassion may be as desirable as moderation of passion. Jude Law’s remarkable Karenin is also given an unusual measure of sympathy for this reason.

The exultant bits are of course in the parallel love story of Kitty (Alicia Vikander) and Levin (Domhnall Gleeson), whose down-at-heels country estate and what goes on there are given a more realistic presentation, and thus one more in keeping with the nature of the medium, than the claustrophobic, hot-house settings in Petersburg and Moscow which incubate Anna and Vronsky’s fatal fancy. As in Tolstoy, Kitty and Levin’s paradigmatic marriage offers its moral contrast with Anna’s illicit passion, but without suggesting the sort of authorial preachiness we might otherwise expect. It wouldn’t be easy for any movie to make a line like Levin’s — “Sensual desire indulged for its own sake is the misuse of something sacred” — sound other than jarring and unnatural. But I think this one manages it, and partly by the general lowering of the emotional temperature so as to allow its moral reasoning to emerge as reasonable and in accordance with nature rather than hectoring and imposed on us against our will. A fancy for goodness, bred in the mind, may in the end be as desirable as that for beauty, bred but also dying in the eyes.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.