Unreal Realities

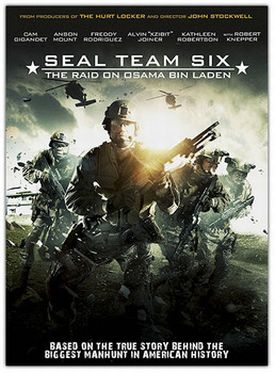

From The American SpectatorSo sorry. I know you’ll be disappointed, but I find my deadline for this issue fell too early for me to offer you a review of “SEAL Team Six: The Raid on Osama bin Laden,” due to appear on the National Geographic Channel on November 4th and on Netflix the following day. On the day after that I’m told there’s some sort of election scheduled. And although it’s true that the thrilling tale of SEAL Team Six has been re-edited to give a larger role in this military operation to the Commander in Chief, we have it on no less an authority than The New York Times that the added tribute to the heroism of our wartime leader had nothing to do with politics. The film, write Michael Cieply and Brian Stelter, “is being backed by Harvey Weinstein, a longtime Democratic contributor and one of the Obama campaign’s most vigorous backers,” but what of that?

In a joint interview on Tuesday Mr. Weinstein; the film’s director, John Stockwell; and others said the changes to the film were not politically motivated but were meant to give the film a stronger sense of realism. . .And Howard T. Owens, the president of the National Geographic Channel, who joined the call, said his company had insisted on removing a scene that showed Mitt Romney appearing to oppose the raid. “We wouldn’t air this if it were propaganda,” he said.

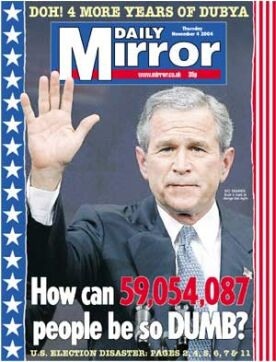

Of course not! The idea! Yet even the Times’s own Alessandra Stanley had to admit that the film “is no more, or less, a work of propaganda than ‘DC 9/11: Time of Crisis,’ a gauzy 2003 salute to George W. Bush’s leadership by a conservative filmmaker, Lionel Chetwynd.” One gathers that she thinks both are propaganda. Like Mr Obama’s own claims of moderation and bipartisanship in contrast to Romneyesque “extremism,” the renunciation of propagandistic intent is so obviously untrue that no amount of mere love for the President would be enough by itself to prevent it from failing the laugh test. No, what does that is the sort of partisanship which approaches religious faith in eliciting the will to believe. Hence the “stronger sense of realism” that the film-makers say results from the increased presence in it of Mr Obama.

I take it that by “realism” they don’t mean the quality of being more true-to-life but something like “more in keeping with the model of reality we believe in.” Given the Weinstein-Stockwell-Owens model, the President’s heroism is mere verisimilitude. Yet we can see in the disclaimers of propagandistic intent, even if we assume they were made in good faith, a tacit admission that there are other models of reality in which this is not the case, in which the President only did what any president would have done by giving the go-ahead for a mission planned and executed by others and then attempted to turn those others’ efforts into a political advantage for himself. “Is all in how you look at it,” as Stan Freberg’s parody Indian chief says to Columbus in claiming to have discovered him rather than the other way around. So, too, we must suppose that Harvey Weinstein has his reality and I have mine. We each have a presumptive right to our own version of the real. Is there then no way to resolve the dispute between the rival editions of reality — to get, as it were, at the real reality?

Perhaps we need to take another look at the idea of “realism.” Verisimilitude must retain some attachment to real reality and not just the subjective kind. Which picture, for example, looks more real to you: that of the strong confident leader inspiring SEAL Team Six with the heart and stomach necessary to pull off their extraordinary mission or that of the guy who, when the plea for help came in from our guys in Benghazi, had urgent business elsewhere (a fund-raiser in Las Vegas) and left them to die? If both cannot be real, which picture looks more like the President Obama we have come to know over the last four years? And if Messrs. Weinstein, Stockwell and Owens say the former rather than the latter, they are deceiving themselves. Their reality-model, in other words, needs adjusting, since this particular part of it just doesn’t look real. What does look real is the emerging story of Benghazi, in which help was denied, or sent too late, to the besieged Americans in the consulate there, presumably for fear of being “provocative” or “escalating” the conflict.

That looks real enough because it fits with the “anti-war” mentality, which supposes any attack on America or Americans must be as a result of something America or Americans have done to provoke it — a mentality which has been typical of the President since his now-infamous “apology” tour — another reality that his backers keep loudly insisting isn’t real. You can see this mentality at work in Ben Affleck’s movie (he both directed and starred in it) Argo, which in one way is a classic American success-story — the extraction by subterfuge of six American diplomats who hid in the Canadian ambassador’s residence in Teheran in 1979 when their diplomatic colleagues were taken hostage by Iranian revolutionary guards. You might even call it patriotic, in that the Americans are the good guys and the Iranians the bad. Just like old times! But look more closely and you will see that it is the Americans of the 1970s who were the good guys. The Americans of the 1950s, however, are carefully set up to be the real bad guys, since they helped the British to engineer a coup against an Iranian good guy named Mossadegh in the interest of Western oil companies. “We did it to them first,” as one of Mr Affleck’s CIA guys explains to another by way of explaining, if not justifying, the Iranians’ hostage-taking.

|

In the mouth of a Carter-era diplomat, and one with the glasses, the moustache, the wide tie and lapels of the 1970s, that kind of reasoning sounds all too real. It’s the sort of thing that Jimmy himself might have said. Coincidentally, the former president himself appears in voiceover at the very end of the film to give it his imprimatur — and, by the way, to take his share of the credit for the real-life hero’s efforts in effecting the diplomats’ exfiltration, just as President Obama does for SEAL Team Six. But time has a way of exposing the realities hidden beneath its adventitious surfaces. You have to be pretty far gone in your attachment to the Carter version of reality, which is also the Obama version, not to see how false it looks in retrospect. The same is true of so much else about the 1970s. The death at age 60 in October of Sylvia Kristel, star of Emmanuelle, that quintessential soft-porn classic of 1974, provides another reminder of how that decade seems to have specialized in generating new and exciting realities that now look risibly fraudulent.

Yet how many people continue cling to their belief in them — if only by avoiding any temptation to go back and see Emmanuelle again with the benefit of hindsight. “At last,” said the movie’s tag-line, “a film that won’t make you feel bad about feeling good.” People could only take such stuff seriously in the 1970s because they could also believe in the fantasy of what Miss Kristel’s older contemporary and fellow sex goddess Erica Jong described as “the zipless f***.” Not many people believe in that anymore, which is why Emmanuelle (and Fear of Flying, for that matter) look so comically dated to most of us. One who still believes, alas, is the great Lena Dunham, author of “Girls,” about whom I wrote in this space a few months ago (see “Laughing on the Wrong Side” in The American Spectator of June, 2012). How, one wonders, can she be so blind to the astounding tastelessness of her “Great Guy” ad for President Obama, which teasingly compared her casting her virgin ballot for him in 2008 to the loss of another kind of virginity?

For her, it appears, sex is still no more than the wonderful liberation, the great adventure that it seemed to the original audience of Emmanuelle. How disappointing to find her still living in the 1970s when “Girls” has shown so much brilliance in the ironic demystification of that same ‘70s view of sex — along with its ‘90s incarnation as an adjunct to shopping porn in “Sex and the City.” The Obama campaign’s invention of a mythical Republican “War on Women,” alluded to in Miss Dunham’s ad, depends on the persistence of this 1970’s mentality, which reduces “women” to their supposed freedom — so new and exciting then, so problematical now — to engage in frequent, promiscuous and consequence-free sex acts. Whatever you think today about abortion or birth control or the sexual freedom they have helped to create, you can’t any longer look at them with the simple-minded enthusiasm affected by Lena Dunham, not unless you have signed up for some real propaganda — which is the kind that doesn’t look real.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.