All That Trash

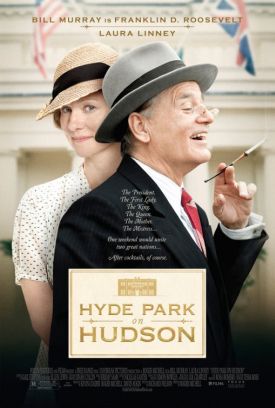

From The American SpectatorWriting on The American Spectator’s website in December, Mark Tooley expressed his disgust with Roger Michell’s and Richard Nelson’s Hyde Park on Hudson, calling it not only unhistorical, which it was, but also “trash” — which it also was. But the realization brought me up short because I had quite liked the movie. And what, after all, did its being trash have to do with anything? It would be hard for me to think of more than a handful of American movies of the last couple of decades or so during which I have been a movie critic that aren’t trash, more or less. Like the famous frog placed into a pot of water which is then brought slowly to the boil, I can hardly be alone in having grown so accustomed to our trashy pop cultural environment that I had failed to reflect on what it was until I found I was being cooked in it. Trash, in short, is the not-so-new norm.

Part of the reason we tend to forget this is that high-brow criticism, proceeding according to the admirable Terentian maxim that humani nihil a me alienum puto (Latin for “Have you seen this amazing YouTube video?”), has long accepted trash culture, along with non-trash culture, as its proper purview — and to that extent may be supposed to have redeemed it, somewhat, from its inescapable trashiness. Still, we can hardly help noticing a narrative of decline, as the high-brows would put it, in the acceptance in serious and learned writings, at first, of obscenity or vulgarisms in quotations, then in the authors’ own voices and, now, in the top headline above the title of the first number this year of the London Review of Books — than whose no brows come higher — which reads, but without asterisks, “John Lanchester: The S*** We’re In.”

Mr Lanchester’s article turns out to be about such arcana as contemporary British economics and fiscal policy and is not concerned with trash culture, but his title could equally well serve for the latter. And the thing about being in the asterisqué ordure for too long is that the condition comes to seem normal — like the appearance in respectable print of a word which was once exiled to colloquial and unofficial contexts. Critics are thus like the Eskimo in the Gary Larson cartoon who greets his fellow with the words: “Well, it’s cold again.” Well, it’s trash again. With that stipulation, however, one really ought to go on to say something a little less obvious, so incurring the risk of forgetting about, for a while, or allowing one’s readers to forget about, the ubiquity of the trash we’re in.

Take the movie Mark Tooley was writing about. It portrays President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Bill Murray) in 1939 as if he were an anticipation of Bill Clinton in 1998 and thus well-immerded in trash culture himself. There, he is joined by his well-named cousin Daisy Suckley (Laura Linney,) with whom he conducts one of many “affairs” — a necessary euphemism, I suppose, but one which also shows how far the old-fashioned critical vocabulary lags behind new realities — which appear to feature, proleptically, the sex act that was briefly to be known sixty years later as “a Lewinsky.” This is, as Mr Tooley suggests, a libel against the memory of a great man, but it provides the occasion for a serious if perhaps mistaken study of the origins of trash culture in the land of the quasi-monarchical presidency which Roosevelt did so much to bequeath to his successors in that office.

Although Miss Linney’s ridiculously sexy Daisy’s slathering mustard on it is an invention of the film-makers, the hot dog consumed by King George VI (Samuel West) at a picnic on the Rooseveltian estate in New York is quite historical, as is the gratification that the king’s lunch gave to the media of the day, as eager to discern “the common touch” in this haughty foreigner as they were to find something of the kingly presence in his American counterpart. It is doubtful that the historical king could have been, as he is shown as being in the movie, so lacking in media savvy as not to have seen in advance what was expected of him by the American mob, but his moment of surprise here as the flashbulbs pop and everyone cheers his first bite of the hot dog is nevertheless a persuasive image of the beginning of a process which was to culminate, long after the king’s death, in the tragically brief career of his grand-daughter-in-law, the late Princess of Wales.

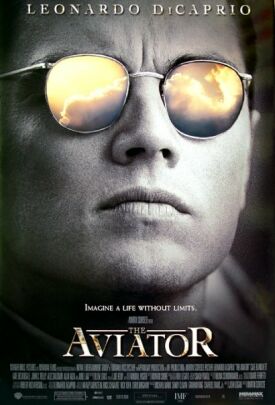

I gather that Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, in cinemas at the same time as Hyde Park on Hudson but much more popular, was also much more historically accurate — which is not to say that it was historically accurate. There, too, however, the trash culture was not entirely excluded, and a soap operatic passage or two between Abraham (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Mrs Lincoln (Sally Fields) and between them and their oldest son, Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), was necessary to reassure us that we were dealing with properly companionable human beings, very much like ourselves, and not those distant avatars of “greatness” they so often appear to be in boring history books. Lincoln himself, universally regarded as the greatest of American presidents, is represented as being so much like ourselves that he is willing to cut legal and ethical corners in order to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery.

Clearly, we are meant to like him all the better for it, as also for his earthy jokes since, like John Lanchester and the LRB, Mr Day-Lewis’s Lincoln uses the s-word to add extra authenticity to his character. Such things add to the sixteenth president’s moral unassailability that touch of the genuine, hot-dog eating down-to-earthness without which it would become repellant to us. If you start from the assumption, as Hollywood does, that all is trash beneath the superficial level, then your touchstone of truth automatically becomes remarkably easy to find. We may not know much about “the real” Abraham Lincoln but we have perfect confidence in our ability to recognize as real those qualities in him, or his screen persona, which are most familiar to us. As a natural skeptic, I tend to assume that anything which makes any historical figure appear to be, as the late Jan Kott used to say Shakespeare was, “our contemporary” must be inauthentic, but then that’s probably no more reliable a rule to follow than its opposite.

|

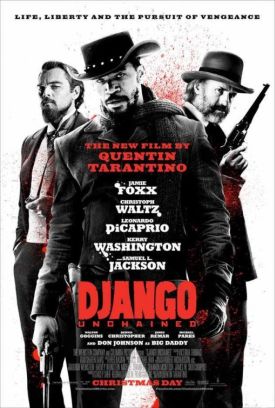

It was perhaps in the Kottian spirit that Quentin Tarantino defended the violence in his new movie, Django Unchained, by summoning Shakespeare to witness when some suggested that his postponing of the movie’s premiere in December, after the school shootings in Newtown, Connecticut, indicated an element of shame about it. “This has gone back all the way down to Shakespeare’s days, all right?” QT told CNN. “When there’s violence in the street, you know, the cry becomes, ‘Blame the play-makers.’” Like the movie itself, this is laughably unhistorical. No one ever blamed “play-makers” for “violence in the street” until recent times, and for reasons that only trash culture could make us neglectful of. For in Shakespeare the violence is incidental to the moral drama, whereas in trash like Django the moral drama is crudely sketched in and deliberately distorted into cartoon form so as to serve as a mere excuse for the violence. The loving portrayal of that is the real point of the exercise and what most people, in their role as connoisseurs of trash culture, have presumably come to see.

But Shakespeare knew not these spurtings of arterial blood, bullet-propelled viscera flying through the air or screams of pain in response to graphically portrayed scenes of torture, all captured in larger-than-real life images on camera, and he would undoubtedly have wondered at those who find such things entertaining. Nor did he feel his artistic freedom compromised by not being allowed to use, as Mr Tarantino does, a popular vulgarism in order to make his characters accuse each other, both untruthfully and anachronistically, of practicing mother-son incest. The point, as I’m sure you will have gathered by now, is that the essence of trash culture, like that of the celebrity culture to which it is so closely related, is to flatter those who believe — as who does not, nowadays? — that although there may be many in the world who are worse than they are, there is none better. Those who are set above us for whatever reason, whether Roosevelt or royalty, Lincoln or Shakespeare, or just because they are on TV, are really just the same as we are — or, perhaps more accurately, are just the same as we would expect to be in their situation. When you find yourself feeling that way, and feeling it with a Tarantinian level of self-satisfaction, you’ll know that’s the trash we’re in.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.