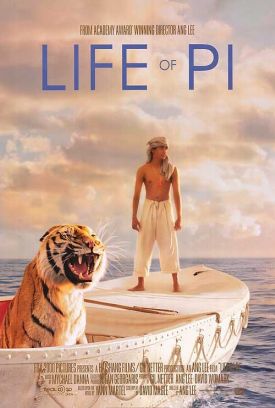

Life of Pi

That they are both nominated for Best Picture of 2012 in the Academy Awards may obscure the fact that Life of Pi is in one essential respect, at least, the opposite of Amour. In the latter film, Michael Haneke is determined to look at both the world and the question of religious belief with despair, whereas in Life of Pi, Ang Lee is entirely on board with Yann Martel’s equally determined but rather naive hopefulness. Both are very well done, if rather one-sided, but they make a remarkable pair of bookends for the problem of belief in our time. Amour takes the cheer out of the cheerful atheism of Richard Dawkins and company and so gives us a better idea of what we’re really getting; Life of Pi is refreshingly unapologetic about its gods while still preserving something of their Old World (or Old Testament) savagery.

Mr Lee brings enormous directorial skill and, with the help of computer-generated imagery, visual artistry to a straightforward attempt at myth-making. Kipling tried something like this in his story “The Knife and the Naked Chalk,” as did John McTiernan’s movie The Thirteenth Warrior, though both were dealing with established myths and purporting to explain them in naturalistic terms. Life of Pi is more ambitious, creating an entirely new myth out of a naturalistic story which is only revealed to us at the end. Up until that point the myth, so splendidly photographed and its story so well told, has things all its own way. Young Pi (Suraj Sharma), aged about 16, emigrates with his family and the zoo they have long owned in Pondicherry, India, to Canada. The Japanese freighter on which they are crossing the Pacific founders in a storm and Pi and a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker are the sole survivors, uneasily sharing the same lifeboat for weeks adrift as Pi by one means or another manages to avoid becoming the tiger’s last meal.

Both boy and Bengal more than once touch the edge of despair and oblivion, and for the former if not the latter this becomes a quasi-mystical experience. Pi, already revealed to us as a spiritually questing person with an allegiance of some kind to at least three of the world’s major religions, takes these brushes with the infinite as the occasion for reflections on life, the universe and everything, but the upshot of all is a firm conviction that one must never lose hope and that God’s Providence, thank God, is little changed since the days when it stood that other shipwreck victim, Robinson Crusoe, in such good stead. “Without Richard Parker I would have died by now,” explains Pi. “Fear of him kept me alert; tending to his needs gave my life focus.” What looked like the blackest of fates became a spiritually transforming experience.

All this story is told in flashback by the middle-aged Pi (Irrfan Khan), now some kind of professor of religion, to an interviewer (Rafe Spall) who has been told by someone else that Pi’s story would compel belief in God. It doesn’t quite do that, but at the conclusion of the story which the film has narrated for us, Pi then tells him a quite different one — one which is duller and less fraught with meaning but more in keeping with what we know about worldly probabilities — and asks him which of the two stories he prefers. Of course, we are as sure as he is to answer that it is the one we have been watching for two hours, the enthralling one with the boy and the Bengal tiger alone on a lifeboat together in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

“The tiger; that’s the better story. . .And so it goes with God.” Or rather, so God goes with it. Religion has always been a matter of stories, as we are reminded by Pi’s early experiences with the comic-book gods of the Hindus, and they tend to be stories with the miracles left in that the Japanese insurance adjusters in this one politely ask Pi to leave out. It’s not good to forget that, as Kierkegaard suggested when he said that the stone rolled away from Jesus’s tomb ought to be called the Philosopher’s Stone, as it has perplexed the philosophers ever since. Yet philosophers are also necessary to point out that, if belief is a matter of choice — the tiger story is the one we like better, after all, not the one most likely to be true — it doesn’t render questions of truth trivial or irrelevant. Just out of the mesmerising shot, as it were, in the beautifully rendered Life of Pi, there is more than a hint of the kind of flip postmodernism that thinks such questions are meaningless.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.