Outrage Against the Machine

From The New CriterionHere’s something that happened in Britain a few months ago. Andrew Mitchell, a Member of Parliament and the recently-appointed government Chief Whip, a man with a reputation for abrasiveness, rode his bicycle to a meeting at Number 10, Downing Street. Let’s stop right there for a moment and reflect on the unlikelihood of such an official’s choosing such a mode of transport on such an errand in the U.S. or, indeed, almost any other country in the world, outside Scandanavia. You might almost think it a sure-fire proposition that Mr Mitchell was angling, like his fellow Conservative and fellow cyclist Boris Johnson, the mayor of London, to be known for his humility and approachability — a true Man of the People as well as a friend of the environment. But on leaving the meeting and approaching the Whitehall entrance to Downing Street his access was delayed at the massive iron gate thereunto which has recently been erected for security reasons. A member of the Diplomatic Protection Group of the Metropolitan Police told him that he would have to dismount and wheel his bicycle through a side gate. He wasn’t happy about it.

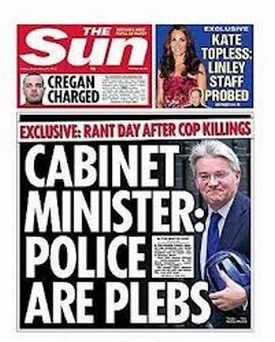

According to the official police log, this simple bicyclist reacted by saying: “Best you learn your f***ing place. You don’t run this f***ing government. You’re f***ing plebs.” Then, as he departed on his bicycle, he added: “You haven’t heard the last of this.” He was also reported to have addressed the policemen as “morons.” Additionally, according to the police, “several members of the public who happened to be passing at the time looked visibly shocked” at Mr Mitchell’s outburst. One such passer-by, by his own account, wrote to his Member of Parliament, by chance a deputy government whip, to complain about it. His e-mail was then leaked to the press, as was a copy of the police log which the e-mail was found to corroborate. After a month of media outcry over the incident and endless analysis of it for its significance as a true indicator of the state of mind of the Conservative-led government and the suspiciously upper-class Prime Minister, David Cameron, Mr Mitchell was forced to resign his government office for the usual reason, that he had become a distraction to the business of governing.

|

He continued steadfastly to deny that he had ever said the words attributed to him by the police report and the e-mail, though he admitted to having said, “I thought you lot were supposed to f***ing help us.” He was not believed. He was not not believed. Rather, he, along with whatever might have been the truth of the matter, was ignored. Neither his political colleagues nor the media, even many in the otherwise sympathetic or Conservative-leaning media, expressed any but the most lukewarm faith in his denials, although Michael Gove, the Minister for Education, invoked Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon as a possibly parallel example of how different perspectives on the same events can radically differ. What is truth, after all, but a matter of perception? That was also the view embraced by the new and very conservative president of the Heritage Association, former Senator Jim DeMint, on this side of the Atlantic after the recent presidential election. The Obama presidency appears to have made us all relativists now.

In the case of Mr Mitchell, at any rate, few in the British media cared what the truth might be. They had got their “gaffe” — the thing many live for here in America as well as there — and they considered themselves entitled to make the most of it, whatever might have been the “exact” truth. Thus the ironically designated Whip was held up to the whips and scorns of the media, as well as of those he considered allies and friends, as a terrible example of his party’s antediluvian sense of privilege and class-consciousness and the government’s lack of sympathy with “ordinary” or “working class” people like the poor abused policemen whom he had called “plebs.” Not that he was entirely without sympathizers. As Fraser Nelson wrote at the time, anticipating his resignation, in The Daily Telegraph

It may all be desperately unfair: Mitchell still insists he never used the word “pleb”. But Humphrey Bogart never said, “Play it again, Sam.” If a catchphrase seems to fit, it sticks. The Mitchell anecdote is so devastating because it perfectly conforms to the caricature of the Tory toff. If he is fed to the lions (or sent to Rwanda), this will be why. Justifiably or not, he has come to represent what Cameron regards as the most potent single threat to the Tory party: the idea that it is a party of snobs, who think they’re born to rule.

In other words, it was only to be expected that the truth of the story must be indeterminate and therefore of less importance to the media than whether it could be taken to fit in with an established media “narrative” about Tory arrogance and snobbery. It was all “desperately unfair” to the victim, of course, but the media gaffe-hunt had to be regarded — irrespective of the truth or otherwise of the gaffe itself — as a force of nature with which it would be futile for anyone to attempt to interfere.

Two months later, just before Christmas, investigative reporters for Channel 4 found that closed circuit television footage from a security camera at the scene did not bear out the official police account of events. Moreover, the sender of the e-mail purporting to be from a member of the public who had witnessed the whole thing was in fact another policeman who had not been near the scene. It was further pointed out that the supposed incident had taken place at the same time that members of the Police Federation, the union representing the rank and file, were protesting against government cutbacks to police pay and benefits. It was also recalled that recent investigations into police conduct in several high-profile incidents — one of which took place twenty-three years ago — had revealed a pattern of lying and corruption to cover up mistakes and misconduct. What had started out as a political scandal had suddenly transformed into a police scandal.

What it never quite managed to become, unsurprisingly, was a media scandal. The media benefitted from it coming and going, of course, as they always do. Whether it was Mr Mitchell who was the scandalous one or the Police Federation, or rogue police officers, or somebody else entirely made little difference to them. The caricature of the arrogant and unfeeling Tory toff obviously suited their “narrative” best, but if that was no longer operative, the newly-unveiled image of the corrupt and lying policeman would do almost as well. Either way, they had a painted devil on a stick to display to a scandal-hungry public for the purpose of eliciting an essentially manufactured outrage. Little or no notice was taken nor any mention made of the fact that, in pursuit of the gaffe, the media had allowed themselves to be used — to put it charitably — by people with a political agenda which was obviously furthered by blackening the reputation of an innocent man.

By a remarkable coincidence, the pre-Christmas revelations about what was by then being called “Plebgate” came out just as the British media and political class were debating their response to the report of Lord Justice Leveson’s Committee of Inquiry into the culture, practice and ethics of the press, a committee that had been set up in response to the phone-hacking scandal at the now defunct News of the World the year before. The committee’s report had called for independent regulation of the press and, in particular, a much more careful scrutiny of unofficial contacts between the police and the media. These restrictions the latter, and especially the tabloid Daily Mail, objected to, seeing them as a possibly fatal discouragement to bona fide leakers and “whistle-blowers” seeking to protect the public — as well, of course, as to self-interested scandal-mongers seeking to protect themselves.

Michael White, blogging for The Guardian, agreed that protecting whistle-blowers and leakers from the rigor of the law was a matter of moment, but he added that the Mitchell affair showed how

leaks carry a health warning that some award-winning hacks never read. It is motive. Why is he/she telling me this? And is it true? At this point Fleet Street falls into a familiar elephant trap along with the police trade union, the Police Federation. Nowhere does the Mail’s news report or the blowhard column written by Richard Littlejohn give any consideration to the aspect of the affair that the Guardian reports, namely that one of the investigative lines of inquiry is not simply an unauthorised leak or two but the — to my mind, important — possibility that the leaked version was untrue in key respects. So the point of principle — the protection of whistleblowers — is rightly defended in Fleet Street while the point of practice — the Street of Shame’s cheerful willingness to print any old bollocks the lawyers say it can get away with — is ignored, as usual.

The most revealing bit of that passage is the parenthetical phrase, “to my mind, important,” appended to the question of the truth or falsity of what the media report. He knows, that is, that it is no longer a universally-held view among his journalistic colleagues, but he is just enough of a traditionalist, a reportorial stick-in-the-mud himself to believe that truth is — well, not essential but at least “important.”

“Plebgate” had happened along at exactly the right moment to illustrate his point about the morally and intellectually problematic nature of that journalistic stock-in-trade, the leak. Not that anyone in the media was disposed to take very much notice of it. Like Fraser Nelson, most people seemed to regard the sort of media scandal-mongering that thrives on leakers, whether public-spirited or self-interested or a little bit of both, as a fact of life about which little or nothing could be done. Some, indeed, went on record as saying they had always believed in Mr Mitchell’s innocence even if they hadn’t said so — or at least that they had always known there was something “a bit off” about the police account. But they, too, had so far accepted the media narrative about the class-bullying Tories which the original story had seemed to confirm that they were prepared to believe he had said something which it was always highly unlikely that a man in his position would or could have said. The former M.P. and columnist Matthew Parris of The Times asked himself in print the searching question of why he had believed what he now says he instinctively hadn’t believed about a man whom he regarded as a friend. Unfortunately, he never got around to answering his own question.

Surely the answer must have had something to do with a residual unwillingness to believe in the bad faith of the police or the media and a corresponding willingness to give them the benefit of a doubt that has long been denied to politicians — partly as a result of the media’s own assiduity, in the decades since Vietnam and Watergate, in breaking down people’s trust in their political institutions and those who serve in them. All this casts an interesting light backward on my reflections about lying and the charge of lying in politics, published in this space (see “Lexicographic lies” in The New Criterion of October, 2013) just at the time when the British media, suspiciously unsuspicious of any bad faith on anyone else’s part, were calling for Mr Mitchell’s head. It occurs to me now that the frequency with which politicians accuse each other of lying is no reflection of their actual beliefs — how naive of me ever to have thought so! — but an attempt to commandeer for their own purposes the media-promoted meme of the lying politician.

The charge of lying, in other words, is nearly always itself a lie. Moreover, it is recognized as such both by those who make it and those to whom it is made. If they really thought their opponents or critics were lying, their reaction would not be the patently manufactured indignation they display in purporting to think so but something much more like terror — the terror felt by the Somerset farmer whose reaction to “Plebgate” was recorded by Charles Moore of The Daily Telegraph. “It’s terrible,” he said. “The police are supposed to protect us. If you can’t believe them, who can you believe?”

Once, I seem to remember, people had somewhat the same reaction to being told that their political leaders — who are also charged with protecting and serving them, after all — were lying. Now we take it for granted that they are, with what results we can see in the eruption of such pseudo-scandals as “Plebgate.” And so, perhaps on the reasonable ground that they’ve nothing more to lose, we find that politicians do lie, often if not routinely, if only by charging each other with lying. None of this would be possible without the academic and philosophical preparation of the cultural ground which has come from a broadcast sowing of the seeds of doubt that “truth” — rarely to be met with anymore in serious discourse without its punctuational epaulettes — can ever be knowable. Only reverence for what we no longer believe in once gave the allegation that someone was paltering with the truth the kick that the media is forced to pretend it still has.

Another way to put it is to say that the currency of outrage has been debased. The incivility with which our politics is now beset is a product of the media’s bidding war for outrageousness which they can then turn into outrage marketed to an ever-growing customer base for it. Everybody has opinions and everybody wants an opportunity to express them. Doing so is an exercise in self-definition for increasing numbers of people. I am my opinions, and therefore I long to make my opinions heard. But as the expression of one’s opinions — on the Internet, on Facebook or Twitter — has become ever easier, opinion itself has become a drug on the market, which is now so crowded with sellers that the buyers in the media can call the tune, demanding ever more outrageousness in return for their limited attention. In order to get attention for our opinions, in other words, they have to outrage somebody, as all the most successful opinion-mongers appear to have recognized.

Hence, for example, Richard Dawkins’s saying that bringing a child up in religious faith is worse than subjecting it to sexual abuse. An opinion that would have been considered a self-evident absurdity and only laughed at a decade or two ago is now taken seriously because it can be exchanged for a high price in outrage — outrage both from those who agree and those who disagree — which is the media’s coin of the realm. Increasingly, in order to be heard you have to be wrong, and the wronger the better, since simple or minor wrongnesses, never mind rightnesses, are ten a penny. Being outrageously right, on the other hand, is less and less possible, not only because there is an inherent calmness and reasonability about the truth that does not lend itself to such excitement but also because truth tends to be familiar and to lack the novelty — always an essential ingredient in outrage — of error. As a result of the media market for outrageousness, it has become harder and harder for truths, particularly unpalatable ones, to be heard at all.

That must be one reason why in the recent US election campaign there was hardly a mention of some of the biggest problems facing the country, most notably the debt crisis. Instead, the media focused — and only partly to oblige the campaign designed by Democrats — much more on non-issues like birth control, abortion and rape, Republican views of which, however outrageous, could have had no political consequence whatsoever but which could serve to illuminate a Democratic-media narrative about the lack of caring about or empathy with or understanding of women by the likes of such GOP troglodytes as Todd Akin or Richard Mourdock. Even Messrs Romney and Ryan couldn’t muster as much outrage about high unemployment, slow growth or multiple trillion-dollar deficits — they hardly even seemed to try — as their victorious opponents did about monsters such as these, or about the “binders full of women” which were supposed to have put Mitt Romney in the same camp of declared enemies to American womanhood.

To be sure, such a cynical campaign could not have succeeded without the help of the media’s commitment to “progressive” goals, but those goals lend themselves particularly well to the media’s trafficking in outrage. All the world’s victims, or those who fancy themselves as victims, are customers for such outrage on behalf of the compassionate, or those who are to be compassionated, whereas the party of self-reliance, small government and fiscal responsibility is always going to be the low bidder in that media market. That’s why Jim DeMint believes that his party has to make its peace with a media environment in which perception is reality. As with Andrew Mitchell on the other side of the water, the demands of the media model take precedence over those of the truth — which, no longer being supposed to be accessible, could have no demands anyway, except for such nostalgists as Michael White or myself who retain a sentimental attachment to our belief that it exists at all.

|

At least Mr Mitchell is now widely supposed to be in line for some sort of political rehabilitation. That’s more than is ever likely to be vouchsafed Mr Romney. A defeated presidential candidate nowadays has, ipso facto, something of the taint of scandal about him. This is because the outrage market demands his characterization not just as a bad potential president but as a bad man, and because the electorate has, in effect, validated that characterization. This was not the case back in the days when Thomas Dewey or Adlai Stevenson could win their party’s nomination again after having been once defeated — or, in the case of Richard Nixon, could even come back from defeat to win on the second try. Nixon, whose centenary was celebrated by a surprising number of die-hard loyalists in Washington last month, was both the last president of the era of trust and the first of our own age of media-driven scandal politics. The legacy of peace that his remaining friends and supporters cheered now seems likely to be outlasted, alas, by that legacy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.