42

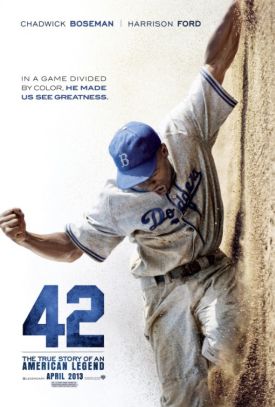

Spoiler alert! I’m always surprised and a little chagrined at the fetish so many people make out of being surprised by a movie’s ending, as if every picture were by Hitchcock and could only justify the demands it makes on our time by repaying our attention for an hour and a half or so with five minutes of a surprise ending wrapped up for us like a Christmas present with a bow. But there it is. People insist on being surprised and scorn those who spoil the surprise for them. Except when they don’t. From the start of Brian Helgeland’s Jackie Robinson biopic, 42, we already know how it comes out. Of course this is also true of Titanic, as it is of lots of movies based on well-known real-life events. But some kids had never heard of Titanic before they went to the movie, whereas no one doesn’t know that black guys have been playing in the Major Leagues for a long time now. Jackie, we know, has got to triumph in the end.

Perhaps I am just sour because, as a native of the state, I resent the movie’s blatant anti-Pennsylvanian prejudice. In this ostensibly anti-discrimination picture, Philadelphia is portrayed as a hotbed of racism, worse than Birmingham. When the Dodgers arrive in the City of Brotherly Love with the rookie Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) for a road game against the Phillies, the Ben Franklin hotel proprietor bars their way, for all the world like a Yankee version of George Wallace in the school house door. The Phillies’ owner tells Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford),”We’re not ready for that sort of thing here in Philadelphia,” and the Phillies’ manager, Ben Chapman (Alan Tudyk) spews so much vile racist abuse at Jackie during a game that he almost, for the only time in the picture, provokes a violent reaction. In fact he does provoke one, though Jackie’s rage is only taken out on a bat, which gets him a hug from Mr Rickey. As if all that weren’t enough, Pittsburgh is treated as if it were at the end of the earth, and being sent there as if it were the worst thing that could happen to a pro ballplayer in 1947.

Perhaps for this reason, I am not entirely happy about accepting the movie’s potted history of the period, any more than I am its insistence on the saintliness of Jackie Robinson — though I must admit that I find the nostalgic glow it manages to create around its loving recreation of the material look and the musical sounds — nothing like those big-band numbers for atmosphere — of the immediate post-war era as seductive as I was meant to find it. It’s a little less persuasive about the moral characterization of the people, and not just those in Pennsylvania. We cannot but be aware that the thing has been set up to flatter us with a demonstration of our superiority to these benighted racists who were — let’s not kid ourselves — younger versions of the parents and grandparents of many of us. As one reviewer put it, the movie makes “a case for being on the right side of history.”

As if that was a case needing to be made! As usual when you hear someone mentioning the putative sides of history nowadays, you also know in advance that the right side of history is our side of it, the side facing away from it and looking in another direction — often at itself, and with a good deal of smugness. In fact, it’s pretty hard to think of any movie of the last twenty or thirty years that is set in the past and that makes the past look like somewhere you’d like to be yourself — though that’s what movies were often like in the olden days, now lost to history themselves, when historical epics were about knights or cowboys or princes or pirates. Now history is just a convenient grab bag out of which a progressive-minded film-maker can draw examples of why you would never want to be anywhere but comfy and warm in the present day, away from the wrong beliefs of our primitive ancestors of only a generation or two ago.

It’s part of a more general tendency of today’s pictures to tell us only what we’re already supposed to know. Thus, insofar as Leo Durocher is today remembered at all, it is for having said that “Nice guys finish last.” So, of course, in his brief appearance here, played by Christopher Meloni, he has to say “Nice guys finish last.” He does so in the context of welcoming the news that Jackie Robinson is not a nice guy as he understands the term (i.e. soft) while he, Durocher, is in bed with a young woman not his wife. This makes a nice segue to the one-year suspension Durocher suffered in 1947, Robinson’s rookie season with the Dodgers, because of a threatened boycott over his sexual misbehavior by the Catholic Youth Organization. This, perhaps the most outlandish of the film’s period details to audiences today, we may take to be in the film-makers’ eyes nearly as discreditable to the 1940s as their endemic racism.

To me, the most interesting moment of 42 comes when Eddie Stanky (Jesse Luken), the Dodgers’ scrappy second baseman, confronts Ben Chapman on the field about his racist heckling of Robinson, threatening to shut his mouth for him if he doesn’t shut it. Back in the dugout Jackie, with some apparent reluctance, says thanks. “For what?” Stanky replies. “You’re on my team. What am I supposed to do?” Of course, it helps to know that not just racism but needling and insulting any and all opposing players on the basis of their appearance or their ancestry or anything else that might get under their skin had been a normal part of the rackety and low-class game of baseball from the start, but it seems to me that a more interesting, less familiar way to read the Jackie Robinson story is as one of the gentrification of our national game with a new and classier approach to sportsmanship.

At any rate, one wishes Mr Helgeland had made more of this moment to see beyond the now predictable story of the gradual enlightenment of the racist troglodytes of another era and give us instead a glimpse of the power in any era of factional or team spirit — a cousin of racism, at the least, if not quite the same thing — to supersede less productive forms of prejudice. The New York Times obituary of Eddie Stankey called him a “spark plug” for three different pennant winners, a guy of whom Durocher said, “He can’t run, he can’t hit and he can’t throw. But if there’s a way to beat the other team, he’ll find it.” The will to win is mentioned by both Rickey and Durocher as their reason for welcoming Robinson to the Dodgers, but the movie’s spirit of self-congratulation makes it too easy for us to forget about this.

By the way, the historical Eddie Stanky was also from Philadelphia.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.