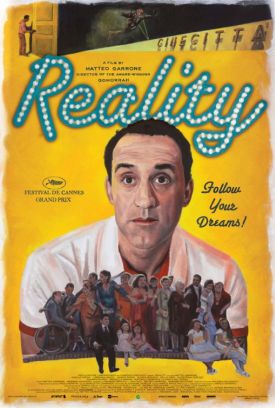

Reality

Matteo Garrone (Gomorrah) has had the bad luck to have his new movie, Reality, labeled a satire of reality TV. People, some of them critics, therefore think they know what to expect and express disappointment when they don’t get it. But Reality is not a satire of reality TV. Reality TV, as represented by “Grande Fratello,” the Italian version of “Big Brother,” and the celebrity culture it panders to are both assumed to be as vapid and mindless as we pretty much already know they are. That’s not a proposition which is in much need of demonstration. Instead, these things provide Mr Garrone with a vehicle for a much more profound examination of human life and what people need to give meaning to it than any mere satire could accomplish. It would be better to see the movie as a gloss on that quotation, once erroneously attributed to G.K. Chesterton, about how when people stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing, they believe in anything.

The movie begins with an aerial shot of a Cinderella coach driven by two white horses taking a bride and groom through the streets of Naples to their wedding reception at a magnificent hotel. What we are about to see has nothing to do with them, or the hotel, though the fairy tale part should be borne in mind as being of particular relevance. It is, rather, the story of a fishmonger and small-time scam artist named Luciano, played by Aniello Arena who is a real life criminal working on day-release from prison. Mr Garrone had seen him in prison theatricals and thought he was the only actor in Italy with the right, “working-class” sort of face. Luciano is at the wedding, we gather, because another of his sidelines involves dressing in drag and performing at weddings and other events like this one. Here, however, he is a minor figure compared to the star of the show, who is neither the bride nor the groom but a man named Enzo (Raffaele Ferrante), seemingly known to all present for having stayed for 116 days in the “Grande Fratello” house. When called upon to say a few words, Enzo delivers a little inspirational spiel about never giving up, out or in and holding on to your dreams. He is introduced to the crowd as being himself one who “found his America right here in Italy.”

At this point, Luciano seems no more or less impressed by Enzo than everybody else is, but he seeks him out for a photo and an autograph, which being granted some kind of seed must have been planted in him, for he soon gets it into his head that he, too, might do as Enzo does and enjoy the life of a celebrity — if only he can be chosen to be among those who inhabit the “Big Brother” house in a new season. His family encourage him to attend a local audition, and he soon persuades himself that he must be, he will be chosen. Much to the distress of his wife, Maria (Loredana Simioli), he sells his fish-stall in the market and gives up his other business, which appears to involve taking advantage of some government program to supply kitchen appliances to old women who don’t want them and who sell them on to him at a discount.

This business he decides to get out of when he comes to believe — as part of the elaborate delusion he has spun around himself — that he is being watched, Big Brother style, by “the financial police,” or perhaps by the producers of the show themselves, to make sure he is living within the law. Soon he imagines himself to be under constant surveillance by those who are testing him, to make sure he is worthy of being on the show. The key line of the movie comes from Luciano’s cousin and right hand man at the fish stall and in the scam operation, Michele (Nando Paone). When Luciano first starts to imagine that he is being watched, Michele says: “We are all being watched — by God.” Whether it is this suggestion which takes root in Luciano’s disordered brain or for some other reason, he starts treating “Big Brother,” in both real and imaginary incarnations, as if it were God the Father.

Thus, when he is called in to a second interview at Cinecitta in Rome, which is treated as a fairy tale palace where dreams can and must come true, he emerges as if from a priestly absolution. “I told them everything,” he proudly tells Maria, “even about the past. Most people were given only a few minutes, but they kept me for an hour. I told them things I never even told papa. I shocked them.” When a beggar asks him for a handout, Luciano shoos him away but then calls him back and treats him to a meal. Before long, he is giving away all his possessions, in spite of Maria’s frantic pleas, to a phalanx of homeless people who are now following him around. “Just a little charity for the poor,” he reassures her, quoting from Mark’s gospel: “It will come back a hundredfold.”

Above all, even when it is clear that he has not been chosen among the “Grande Fratello” elect, Luciano clings to Enzo’s maxim about following one’s dream and never giving up, even stalking Enzo himself in order to be reassured on the point. He also encounters two pious sisters, who may be hallucinations but who further reassure him: “Be patient. Only death has no remedy. Everything else works out. If you want to get in the house you will.” In the final scene, the opening aerial shot is reprised in reverse. Instead of zooming in from above on the fairy-tale, the camera pulls back, ending in a look down from far above on Rome at night and Luciano in a spot of light at Cinecitta that, for him, must amount to inhabiting a beatific vision of ultimate felicity. He has held on to his dream, and it has come true as he always knew it would — even though its truth is only the truth of dreams.

In an interview with The New York Times Mr Garrone said this: “For many people, to be on television, it means to exist. For some, what happens in television is more real than what happens in real life. Television is a sort of certification of reality. So for Luciano, it became almost existential, his desire to be on ‘Big Brother.’ It turns into not just him wanting to be rich, but something more.” The “something more” is a meaning and purpose in life for which, to him, it is worth giving up everything. People used to understand that kind of thing a lot better than they do today, which is why some critics look at Reality and can see only a satire of something that is entirely self-satirical. It is also why poor Luciano thinks that he will find his life’s purpose and meaning only in something that has neither.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.