Great Gatsby, The

Everybody remembers the last line of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most celebrated novel, The Great Gatsby: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” I’ll come back to those words in a moment. But how many of us remember the novel’s first lines? “In my younger and more vulnerable years,” Fitzgerald wrote in the voice of his narrator, Nick Carraway, “my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.’” Nick then goes on to compliment himself for generally following this advice and “reserving judgments” about people but also to point out that, like his father, he does so condescendingly (he says “snobbishly”). He then adds that his tolerance has a limit and implies that Gatsby, in the story he is about to tell, is it.

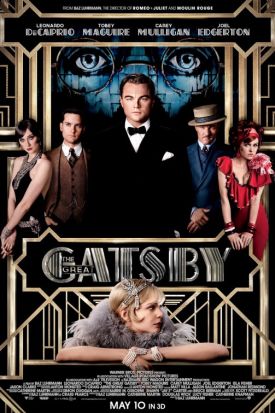

For the most part, Baz Luhrmann’s new movie version of the novel sticks very closely to Fitzgerald’s words. Sometimes too closely. In several scenes, set in a completely un-Fitzgeraldian asylum at some unspecified later date where Nick, played by Tobey Maguire, has been instructed by a psychiatrist to write his story down, we see the words actually on the screen (and, like the rest of the movie, in 3-D). But in the case of the opening lines, there is a subtle change. Instead of advising his son to reserve judgment of the less fortunate, the movie’s account of the senior Mr Carraway has him telling his son not to make any judgments of people at all. It’s a crucial difference which can stand for what, above all, distinguishes Fitzgerald’s world — a world in which morality and principle were things people of all classes were expected to take an interest in, as well as to behave in accordance with — and our own non-“judgmental” present where the only good is inclusiveness and the only evil is discrimination.

We tend to forget — or so I conclude after watching Mr Luhrmann’s picture — how very different this makes us, not only from Fitzgerald but from the whole world he was observing as well as creating in The Great Gatsby. To him West Egg, Long Island, and Manhattan, Louisville and Wisconsin, were meant as representations or imitations of real places where the people were meant to behave as the real people in those places behaved. He told some stretchers, as Huck Finn would have put it, but mainly they do look like real people too. By contrast, Baz Luhrmann belongs to a movie culture that has long since cut its ties with the real world for the dubious pleasure of indulging itself in fantasy and mere spectacle. As a result, none of the people in this movie look or behave as if they came from the places they are supposed to come from or are living in the time they are supposed to be living in. They all live in some vaguely Californian, non-judgmental present — which, when you think about it, is what Gatsby was written to warn people against.

Consider the irony. A novel whose principal concern is with the moral poverty it sees as lying just beneath the glittering surface of the life lived by the rich and celebrated of its day has been adapted by someone every bit as blinded by glitter and celebrity as Gatsby was. To be sure, this is not the first time this has happened. The commercial tie-ins designed to sell “the Gatsby look” or style, as well as the movie, all happened back in 1974, too, when the Robert Redford-Mia Farrow version of the story came out. Mr Luhrmann is not the only one to feel quite unembarrassed by his own Gatsby-like love of vulgar display and is probably right in expecting his audience fully to share it. Few, he must imagine, will miss the tedious moralizing of the novel that readers since Fitzgerald’s own day have often felt was merely tacked on by a writer who was, like Milton according to Blake, “of the devil’s party without knowing it.”

Yet without the moral framework, the story loses all coherence. Take that last line, for example. To Fitzgerald it must have meant that the Gatsbyean hope of abolishing the past had proved illusory, like those exciting new freedoms which people of “the Jazz Age” sometimes imagined had freed them from the old and seemingly outmoded truths of honor and morality. But non-judgmental Baz Luhrmann apparently still lives within that illusion, and so his quotation of the line about being borne back into the past makes no sense. What past? And why not be borne back into it, anyway, when it’s just as cool as the present? He’s firmly with Gatsby in that key moment, repeated with cinematic emphasis in the trailer, when he says to Nick: “Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!” But to repeat the past is to abolish the past, qua past, whose distinctive quality is its unrepeatability, and in this sense the film itself is an exactly comparable exercise to Gatsby’s Project Daisy.

For just as his Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio) wants to abolish the five years between the movie’s now and his fondly remembered Louisville romance with Daisy (Carey Mulligan) — the years of her marriage to Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) — so does the film want to abolish the nearly ninety years between our now and the Jazz Age, and with the same object: to make it all come out differently this time. Fitzgeraldian disillusion can be wiped away, or so we are meant to suppose, like grime on an old photograph, while Jay-Z and friends, cheekily teleported along with their distinctively 21st century hip-hop sensibility back into the 1920s, can show us the way to make the party go on forever. “Politicians all move for money,” raps Jay-Z, obscurely a propos of Jay-G, in the charming “100$ bill”

What the hell are we callin’ them?

Low life, I’m crawlin’ out,

911, I Porsched it out.

Y’all niggas so hypocrites,

Y’all know what this s*** is all about:

100 dolla’, 100 dolla’ bill, real, uh.

Gatsby himself could hardly have said it better.

|

But the fantasy of timeless good times lacks sufficient courage of its fantastical convictions to change the novel’s ending — which is thus reduced to a sort of gangsta-style fatalistic flourish. Nick’s parting salute to his friend, “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together,” is practically incomprehensible in the circumstances, unless it means something like: “You’re way more fun than they are.” Of course, such a vulgarization of the property is only to be expected from Hollywood, even by way of Sydney, where “Baz” hails from and where his Gatsby was made. But to me the odd thing is the unwillingness of anyone to criticize it for leaving out the moral dimension that Fitzgerald made so much of.

Here, for instance is what A.O. Scott of The New York Times has to say about the movie’s treatment of Fitzgerald’s moralism. “Much as we may enjoy the spectacle of money, we usually prefer it to be accompanied by sentimental lessons about how there are more important things. We like cautionary tales about the dangers of greed and reassuring distinctions about the sources and uses of wealth.” Sentimental? Does he mean that there really aren’t any more important things than money? I suppose he must, but only as a sort of non-judgmental way of attributing the belief to some general “we” to which he himself belongs only by virtue of his contemporaneity. “Intentionally or not,” he continues, “Mr. Luhrmann stripped The Great Gatsby of the sentimentality that has always been part of its appeal, and in doing so updated it in a radical and troubling way. The result may be vulgar, but it is also an honest reflection of contemporary values.”

So that’s all right then. The suggestion there is that the “values” are somehow validated for artistic purposes merely by being “contemporary,” and we — like Mr Scott, like Baz Luhrmann — remain free to disaffiliate ourselves from them (or not) through a permanent reservation of judgment. Perhaps the ultimate irony lies in the fact that the value “we”, like Nick Carraway’s cinematic father, really do subscribe to, namely that of extreme tolerance for those without any aspirations to goodness beyond the good life of self-indulgence, could be described as a new, more politically correct version of “the American Dream” that the novel is so often said to embody. Now, the American dreamer dreams not of money, which he takes for granted, but of adolescence with no expiry date and a timeless revel in the pleasures of the senses tinged only with a vaguely political resentment against the “hypocrisy” of the rich — or politicians — that never needs to bother with moral maturity. In that sense, we really are “borne back into the past,” except that it is a past which is indistinguishable from the present — and from which there appears to be no escape.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.