Wincing at Cumberbatch

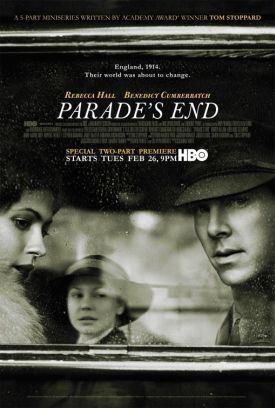

From The American SpectatorAs a long-time admirer — even an enthusiast — of Ford Madox Ford’s tetralogy of novels (Some Do Not, No More Parades, A Man Could Stand Up and The Last Post) that go under the collective title of Parade’s End, I expected not to care for Tom Stoppard’s much- abbreviated adaptation for BBC television, directed by Susanna White, which was broadcast in the UK last year and which came to HBO earlier this year. How could even Sir Tom hope to reduce Ford’s densely written modernist novels to a watchable miniseries that would also be faithful to the original? In the event, I was pleasantly surprised that he did as well as he did — though not surprised that he omitted the final novel entirely, as Graham Greene did in the Bodley Head edition of Ford’s works in the 1960s, claiming to regard it as “an afterthought which [Ford] had not intended to write and later regretted having written.”

My own view of the matter is rather different, but the larger problem with the new miniseries lies in its mere reaffirmation of an understanding of World War I that has gone from being a commonplace to a cliché in the years since Ford wrote — namely that the war was the great watershed of recent European and even American history, an eternal dividing line between the “Victorian” (as it is now often called) and all things old and traditional on the one hand and the progressive, the modern and the modernist on the other. I myself used Ford’s novels as the introduction to my chapter on the interwar years in my book Honor, A History, because, in my view, they offered the most artistically satisfying version of that “end of an era” cliché (as it has since become) and the one most in sympathy with the old honor culture.

Yet the hero of the novels, a Yorkshire gentleman named Christopher Tietjens (played in the Stoppard adaptation by Benedict Cumberbatch), describes himself not as a Victorian but as a man of the 18th century, “the last megatherium” who has unaccountably survived into the post-Victorian era. The Victorians, in his view, would have been too Romantic, too sentimental, too Catholic. Ford, who was a Catholic himself, painted Tietjens as his idea of the Englishman of a more aristocratic, pre-Romantic era, then almost extinct and now altogether so, whose moral foundations rested on the pillars of reason, science, Protestantism and gentlemanly behavior — including, perhaps especially, emotional and sexual continence. At one point he says: “I stand for monogamy and chastity. And for no talking about it.”

The BBC/HBO production, which cost a remarkable $20 million to make, reproduces this line but misses much of the irony in the fact that he is married to an unfaithful wife, Sylvia (Rebecca Hall), and, through her and with her, becomes the talk of London before, during and after the war. There is an open contradiction between the description of Tietjens in the novel, faithfully repeated in Sir Tom’s script, and what we actually see from Mr Cumberbatch, on whose rise to super-stardom Parade’s End is now being seen as a stepping stone. Not only is he said to be large in body — something between an “ox” and a “meal-sack” — but he is also supposed to have facial features of “wood” or “stone.” Mr Cumberbatch, by contrast, is lean and athletic and has mobile features that he doesn’t even try to keep frozen by way of living up in appearance to that which is said to drive Sylvia mad with fury against him.

“I will make that wooden face wince yet,” Miss Hall vows, as if she hasn’t noticed that he does little but wince in the iteration of him that we can see. On several occasions we even catch tears running down Mr Cumberbatch’s manly cheeks. This may seem like a minor point, and it surely has a lot to do with the fact that modern styles of acting — particularly of film acting — are scarcely imaginable without the carefully and conventionally contrived imagery of complex emotions as they are reflected in the human physiognomy. But there is also the problem of making Tietjens’s story, now as out-of-date to us as he himself was said to be to his contemporaries, comprehensible in the eyes of an audience of a century later which has little or no knowledge of its historical context.

In other words, it is very hard to make all that end-of-an-era stuff come across when most of the audience don’t know or care that the era which has ended ever existed in the first place. We may have a vague sense of loss and tragedy about the First World War, born of a thousand literary and filmic adaptations of its history, but we’re a little hazy on the details. Far better, then, for the miniseries — at least from the point of view of those who need to recoup the costs of making it — to pour Ford’s much more interesting but much less comprehensible understanding of the history of his times into the mold of the current cliché and show Tietjens not as a unique survival of Old England but as just one more among the myriad psychic casualties of the war. Today’s audience wants to see him lose his mind, not his moral compass, and so make him into a tragic figure rather than the comic, or tragi-comic (because self-aware) character he is in Ford’s novels.

“My colors are in the mud,” Tietjens says to Valentine Wannop (Adelaide Clements), the young suffragette whom he loves and who, at the same time, represents so much of what he hates about the progressive ideas that are replacing those that have replaced his own. “It’s not a good thing to live by an outdated code. People take you for a fool. I’m beginning to think I am one myself.” He recognizes that a cuckold is essentially a comic figure, but he is more the victim of his wife’s gossip than he is of her sexual adventures. In fact, the novels are less about the war or its social effects than they are about gossip and the power of gossip to destroy lives. Gossip thrives in an honor culture in decline — that is when reputation remains important but is rarely supposed to correspond to the reality behind it. Tietjens is constantly slandered, by his wife and others, because his example of integrity is a constant reproach to them and their self-conceit of knowing the discreditable truth behind every honorable appearance.

|

But he is also unable to prevent the reality of his own life from slipping ever further away from what he calls the “parade” of moral and honorable respectability that “families of position” were once expected to display before the world. In the miniseries it is someone else who says there will be “no more parades,” but in No More Parades it is Christopher himself who says it first. Such an emphatic sense of ending is what gives both Tietjens and England the tragic “arc” — to use a currently favored critical term — so valued by the makers of the BBC series, but it depends on their omitting The Last Post, which envisions his postwar life with Valentine Wannop and which turns everything back to the tragicomic.

I have lost count of the number of critical comparisons I have heard in which Parade’s End has been described as “the thinking man’s Downton Abbey” or the equivalent. Downton, set in the same period, is TV soap opera in which no “arc,” except perhaps that of the stately home of the title, is visible all the way through. Instead, there are scores of shorter stories of the kind that occupy the gossip-mongers then as now: Lady Sibyl’s running away with the chauffeur or Lady Mary’s pre-marital dalliance with the handsome Turk who dies in her bed. But there are also many examples of noble behavior on the part of these noblemen — a rebellious daughter forgiven, a temptation to sexual incontinence resisted — which I take it have something to do with the hostility that this very popular show has encountered from many critics.

In this sense, it is Downton Abbey which could be said to be the thinking man’s Parade’s End, since there is nothing in the latter beside its lonely hero to surprise us in its corrupt world but much that might alter our preconceptions about the past in the former. Gossip and soap opera are traditionally about the things that people keep secret, the illegitimate children and the secret affairs, but in Downton they are just as often secret moments of goodness and charity, self-denial and humility — things not publicized to the world and that have not come down to us a century later partly by their very nature and partly because they wouldn’t be believed by the cynical audience of today to which Parade’s End, for all its virtues, ultimately panders.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.