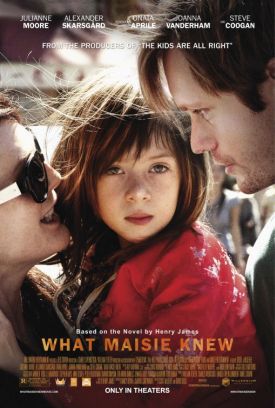

What Maisie Knew

Scott McGehee and David Siegel’s film version of Henry James’s novel What Maisie Knew (the screenplay adapted by Nancy Doyne and Carroll Cartwright) is worth seeing if only for the best performance by a child actor, in my view, since Freddy Highmore’s star turn in Finding Neverland back in 2004. Indeed, seven-year-old Onata Aprile’s achievement as Maisie is in some ways even more impressive than Master Highmore’s Peter Llewelyn Davies, as he was ten at the time Neverland was filmed. Hers is also a more passive character than his, which means that she has the harder task, particularly for a child, of doing most of her acting with her face alone. Her job is to make our hearts break, and she does it with seeming effortlessness.

Complementing her performance are those of Julianne Moore and Steve Coogan as the parents from hell — she a fading rock star and he an international art dealer — both of whom tend to forget about Maisie’s existence even when they are together and make a habit of it once they have split up. Each then marries a much younger person — he Maisie’s nanny (Joanna Vanderham), she a bartender (Alexander Skarsgard) — and their new partners prove to be much more concerned for Maisie’s welfare than her parents are, if no better suited to them as spouses than the parents were to each other. Maisie’s watchful waiting at the center of so much marital and emotional turbulence which she is ill-equipped to understand makes of her an unforgettable portrait of childish innocence, if not altogether the one James intended her to be.

Still, the movie should be commended for setting about the updating of his novel in a more honorable way than Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby did Scott Fitzgerald’s. Where Mr Luhrmann dressed up people of our own day in 1920s-style costumes in order to proclaim an unhistorical identity between us and the people of ninety years ago, Maisie dresses up the people of today as people of today, not of the 1890s when James’s novel was written. It also manages to find rough — sometimes very rough — equivalences between the forms of parental selfishness and irresponsibility most common then and now. Unfortunately, this means that James’s emphases and concerns have had to be changed in many cases, sometimes subtly and sometimes not.

In the former category, we have now to see what started out as a story about divorce as a story about bad parenting. Really bad parenting. So bad that it strains at our credulity in ways that James’s bad parents never quite do. Divorce and bad parenting are not unrelated, of course, but we tend to assume a greater disjunction between them than James’s original audience would have done, at a time when divorce was much rarer and still somewhat scandalous. The verb “to parent” in its contemporary sense had not yet been invented, and I doubt that he or his characters would have understood it if it had, as they belonged to a time and a place and a class of people who would have expected most of the work of being a parent today to be done by someone other than parents anyway. Also, the social proprieties that even the worst characters of James’s era still had to observe add a dimension to his story that simply wasn’t available to its cinematic redactors.

In the less subtle category — and constituting a more serious fault — James’s ending is changed, softened and made merely sentimental by becoming too pat and convenient. But for the powerful impression made on us by Miss Aprile, we might be tempted to see the film as not so much about Maisie after all as it is just another bit of Hollywood propaganda on behalf of a favorite theme — that of the reinvented family. “What Maisie knew” thus becomes the answer to Ms Moore’s question: “You know who your mother is, right?” And just as Maisie’s parents are almost unbelievably awful, so her two step-parents are suspiciously good, if not what you’d call ideal. At any rate, unlike her biological parents, they do genuinely care about Maisie in a recognizably parental fashion, as their prototypes in the novel ultimately fail to do.

The movie has also changed the time frame, telescoping the novel’s events into a much shorter time period — perhaps because its Maisie is so spectacularly good that the filmmakers didn’t dare try to find another child to play her as she approached adolescence. But this may actually help keep before us the child’s eye view of adult problems that is the novel’s greatest strength. That perspective is retained in sometimes unexpected ways. The narrative of the divorce, the remarriage of both partners, then the split of both partners from their new partners as each goes about some adult business barely mentioned, or existing for the child, as for us, only in the form of one end of a telephone call, is told in such bare-bones fashion that it produces an incongrously comic effect on adults. Huh? how did that happen? But in doing so it gives us a share in the incomprehensibility of these adult goings-on to the child.

The parents, after all, are stuck in the same pre-moral limbo as Maisie, but with less awareness of the fact and far less chance of ever getting out of it. There is just one moment near the end when Ms Moore’s bad mother is taken aback by what she sees in her child’s eyes. “Are you afraid of me?” she asks, suddenly seeing herself, if only for an instant, as Maisie sees her. When she assures her that “a long time ago I was just like you,” the words take on an ironic import like that of an earlier assurance to Maisie that she married the young bartender for her sake. There is an absurd failure of self-knowledge there, but there is also an unintended truth in her words. These are ironies almost worthy of Henry James himself and, added to the tremendous appeal of Onata Aprile, they make this movie well worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.