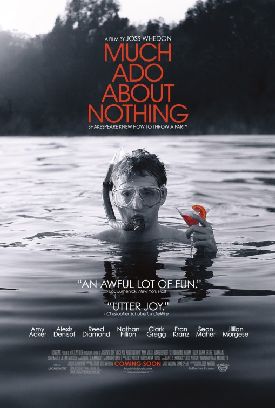

Much Ado About Nothing

Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing makes me feel like giving up. I still believe, believe it or not, that reading or listening to or watching Shakespeare should be an opportunity for us imaginatively to put ourselves back into the 17th century and to see the world, if only for a moment, the way people 400 years ago saw it, in all its savage energy and delight. Of course I know that I have long been fighting a hopeless rearguard action with the progressive-minded, who take just the opposite view of the matter — namely that Shakespeare needs to be purged of anything too redolent of a now-discredited past. That is to say, not only his obscurities but also his Elizabethan political incorrectness must go. So sure are we that he is really just like ourselves under his accidental carapace of old-fashionedness — doubtless adopted in the first place as a disguise to hide his own progressive views — that we feel the need triumphantly to reaffirm it by updating him, both morally and materially. To quarrel with this impulse is as much a critical faux pas as to anathematize (as I also do) cartoon movies. Both can only be the act of a hopeless stick-in-the-mud.

Mr Whedon has apparently set out to show me how wrong I am — about Shakespeare, if not about cartoon movies, in which he also has had a hand with last year’s The Avengers. And his black-and-white Much Ado set in a Californian gated community of the present day (more or less), is so cleverly done that I found myself wondering, after I saw it, whether he hadn’t succeeded. Like the Prince, a.k.a. Don Pedro (Reed Diamond) and Claudio (Fran Kranz) when they team up with old Leonato (Clark Gregg) to persuade Benedick to recant his hard line against marriage, Mr Whedon and his team have wooed me and flattered me away — well, for a moment anyway — from my hard line against the fashionable view of Shakespeare as “our contemporary” by leaving the text almost intact. Apart from some probably necessary cuts and some probably unnecessary smoothing out of obscurities — for instance, Beatrice’s looking forward to leading apes in Hell, the supposed fate of old maids — the only bit of out-and-out tampering with Shakespeare’s words that I can now remember is when Benedick swears to himself (in the text) that if he does not love Beatrice he is “a Jew.” Mr Whedon changes this to “a fool.”

But the result of his verbal fidelity to Shakespeare, admirable though it is, is to produce in us, the audience, a constant sense of incongruity between what we are hearing and what we are seeing — a sense which he seems determined to heighten rather than to mask. This starts in the opening, unShakespearean scene as we see in dumb-show what we will eventually realize is a flashback of Benedick leaving Beatrice’s bed. Later there is another flashback making clear that their relationship has been an overtly sexual one in the past. This takes off from a hint in the text (II.i) from Beatrice about a previous passage of love between her and Benedick (“Marry, once before he won it [i.e. my heart] of me with false dice”), but the visuals of the present day must automatically assume that these words refer to a past sexual relationship between the two — never mind that the whole action of the play is founded on an assumption that such extra-marital coupling is shameful and dishonorable and certainly not a thing that Beatrice could have confessed to.

In a less important but equally baffling way, the small part of Conrad is here given to a woman (Riki Lindhome) — presented to us as a blonde, slutty type who appears to be the plaything both of Don John (Sean Maher) and of Boracchio (Spencer Treat Clark). This overt sexuality (as opposed to verbal suggestiveness) is implausible in itself as anything we might expect to see in Shakespeare, and the implausibility is only increased by the fact that she is still called Conrad, still referred to as one of “these men” or “these fellows” and still addressed as “sirrah,” as she was when, in Shakespeare’s conception for the stage, she was a man and a fellow and a “sirrah” — that is, a servingman addressed with contempt by a superior. The word could not have been used by Shakespeare to refer to a woman. So, too, Margaret (Ashley Johnson) is supposed to be a waiting gentlewoman, and yet we see her prepared to engage in casual sex in front of a window with the likes of Borachio just because she fancies him something rotten. It is not possible to square this kind of thing with all the ostensible value placed on maiden modesty and honor.

Though the dress is modern, it is also exaggerated in its incongruousness. So all the men wear suits and ties all the time — except for a brief, bizarre appearance by Claudio in the pool with mask, snorkel and cocktail. Likewise, all the women wear cocktail dresses, as if they were at a dress-up party. The men are still, as in Shakespeare, supposed to have just returned from a successful military engagement, yet there is no sign of a uniform, and the only weapons are flashy, gangster-type hand-guns. This makes it all the stranger when Benedick swears “by this sword” and there is no sword, or speaks of designing a doublet when there are no doublets or anything like them on view. When Leonato says “hath no man’s dagger here a point for me,” there is not the hint of a dagger anywhere in sight. Leonato has perhaps become unhinged by Hero’s slander and taken, like Macbeth, to thinking there are imaginary daggers in front of him.

Dogberry (Nathan Fillion) and Verges (Tom Lenk), conceived of as a stupid and bumbling LAPD detectives, also wear a suits, which makes the former’s the affected learning and malapropisms look all the more strange and out of character, though not so strange as his references to the latter as a very old man when in appearance he is a good deal younger than Dogberry himself. Perhaps Mr Whedon wants to make him seem even more stupid, but stupidity isn’t what Shakespeare was going for so much as bumptiousness. Friar Francis (Paul Meston), brought in to marry Hero and Claudio, is still referred to as “Friar” even though he is wearing the dog-collar of a secular priest rather than a habit. And why leave out the character of Antonio, especially if references to Leonato’s brother and father to Hero Mark II remain in? Occasionally the newly supplied stage business meshes amusingly with the text, as when Dogberry and Verges lock themselves out of their police car, but for the most part we are too much aware of the cognitive dissonance between word and action.

Most egregiously, all that surrounds Beatrice’s unforgettable command to Benedick to “Kill Claudio” makes no sense at all without some visual allusion or analogue to the contemporary dueling culture, invented in 15th century Italy as a means of social mobility and always in the background (often in the foreground) of Shakespeare’s plays which are set there. This is of course something which is hardly imaginable in present day California. Showing your proposed victim your side-arm, gangsta-style, as Benedick does is hardly the same thing as delivering an old school challenge. “He is now as valiant as Hercules that only tells a lie and swears it,” says Beatrice still, though neither she nor Benedick nor anyone else in the picture has any apparent way of comprehending what she can mean by it. Here is “manhood melted into courtesies” indeed!

Yet I wonder if it is worthwhile to criticize anything, no matter how bizarrely presented, that allows so much of real Shakespeare — in the form of the only thing we have of him, his words — to shine through its unfamiliar dress? This is Shakespeare made, as I suspect the authors think, “accessible,” by which they mean Shakespeare robbed of his mysteries, visually, while verbally left in full charge of them, or close to it. It seems to me that the viewer cannot put the two things together properly. Some of the mystery, which wouldn’t have been any mystery at all in his own time, is easily penetrated. Such, for example, is the high value placed on virginity in women, which was universal in our own culture until relatively recently and still is in many others. But the film seems to feel it necessary to remind us that today it is regarded as a discredited relic of patriarchy and therefore one whose survival among people whom we are otherwise supposed to regard as sympathetic has now become the mystery.

Other parts of the Shakespearean enigma, such as the ease with which Claudio and the Prince are deceived or the imposture of the second Hero, remain mysteries even to dedicated and knowledgeable Shakespeareans. Mr Whedon’s respect for the text at least leaves these mysteries intact, but added to them are now all the other mysteries created by his bizarre updatings, which are too often unShakespearean and gratuitous. Thus he allows one bit of political incorrectness to remain in the text for the sake of a visual joke at Claudio’s expense. For when he says he will take the second Hero to wife “were she an Ethiope,” the film cuts to a black female member of the wedding party. Why? Well, one critic at least thinks, all too predictably, that it is “to make the other guests (and us) wince and reveal Claudio as a racist and unworthy of Hero’s hand.”

See what I mean? It’s not just that nobody in Shakespeare’s day had any idea of what we so glibly describe as “racism.” The use of such pejoratives in order to imply that the Elizabethans had no business not anticipating by several centuries our own hard-won state of racial enlightenment is now a critical commonplace. Thus the editors of the Norton Shakespeare gloss “Ethiope” as “black and therefore, according to the Elizabethan racist stereotype, ugly.” But if Claudio is only now and only thus revealed to be unworthy of Hero’s hand, what we have been watching for the previous two hours is suddenly twisted into incoherence. I don’t see how it is possible for Shakespeare to have intended anything of the sort. Yet the 21st century critic, like the 21st century film-maker — both having been liberated from the necessity of taking into consideration Shakespeare’s intentions, since these are now (falsely) regarded as being unknowable — can take that incoherence in his stride and profess to have enjoyed the experience. For better or for worse and after some reflection I find that I, still, cannot.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.