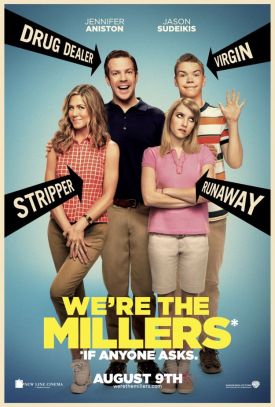

We’re the Millers

In one of the out-takes that play over the closing credits of We’re the Millers, directed by Rawson Marshall Thurber (Dodgeball), three of the primary cast members — Jason Sudeikis, Will Poulter and Emma Roberts — play a prank on the fourth, the lovely Jennifer Aniston. As we see the four seated together in an out-sized “recreational vehicle” in which they are all supposed to be smuggling two tons of marijuana from Mexico into the U.S., Mr Sudeikis fiddles with the car stereo until there issues from it the theme music from “Friends” — whereupon they all start singing along with silly grins on their faces. I guess that the upbeat opening ditty of the NBC TV series which ended in 2004 must be as well known to Americans of the early 21st century as the songs of Stephen Foster were to those of the early 20th. Yet, although I don’t entirely understand it, I also gather that there is something a bit, well, unhip, a bit naff as the British say, about “Friends,” and something a tiny bit shaming to Miss Aniston — or so one gathers from her reaction to the prank as well as the prank itself — about the show that made her a star. Perhaps it has something to do with its warm-hearted idealism?

When “Friends” finally went off the air on a high note after ten years of ratings success, Alessandra Stanley wrote in The New York Times of the connection between the show’s popularity and the contemporaneous social and demographic changes that were happening in New York, the city where it was set. “Suddenly, and in large part because of ‘Friends’,” she claimed, “Manhattan once again looked like a safe, fun and romantic place to be. The six stars of the show became the non-nuclear family that everybody really wanted.” Well, maybe not everybody. Miss Stanley, who also wrote (since corrected) of “the Reagan-Bush recession of the late 1980’s and early 90’s” is rather given to sloppy overstatement. But if she had said that everybody in the entertainment business wanted to be part of a reinvented family made up of friends rather than (as “family” has always been understood until very recent times) blood relations, she would not have been so far wrong. It’s one reason why, in Hollywood as in Manhattan, being in favor of gay marriage is taken for granted. It’s also the reason why We’re the Millers got made.

The movie’s ersatz “family” comes into existence as a deliberate simulacrum of the most unhip version of the real thing — middle class mom and dad and two kids cruising the West in that massive R.V. — as a way of disguising the drug smuggling. Mr Sudeikis is a small-time drug dealer named Dave Clark who is forced by his supplier, Brad Gurdlinger (Ed Helms), to undertake the job after he is robbed of his money and drugs. Mr Poulter plays an 18-year-old named Kenny who, having been abandoned by his mother, is awkward around girls and who looks to Dave as a masculine role model. Just as Dave won’t sell weed to Kenny, thus defining himself to the audience as a decent, principled sort of drug dealer, so Miss Aniston’s character, Rose, a stripper, won’t sleep with the strip-club’s customers on being ordered to do so. Her own high principles are also brought out by contrast with the dim-witted Kymberly (Laura-Leigh), who is only too eager to sleep with the customers, and Rose gains even more sympathy by being the victim of a boyfriend who has cleared out her bank account. “It’s what I get for dating a guy who dates strippers,” say says ruefully.

It’s interesting to see how carefully the movie draws what it obviously regards as these moral boundaries between what kinds of naughty behavior may be engaged in by characters hoping, in spite of it, to retain the sympathies of the American movie audience today. It may be the only thing that’s interesting about it. I couldn’t help thinking of the moment in the fast-talking Professor Harold Hill’s “Trouble in River City” monologue from The Music Man, set in small-town America almost exactly a century ago, where he draws similar boundaries between “a wholesome trotting race” and “a race where they set down right on the horse,” or “medicinal wine from a tea spoon” and “beer from a bottle,” or a “gentleman’s game” like billiards and a putatively scandalous one like pool — all by way of helping him to persuade the good folks of River City of “the calibre of disaster indicated by the presence of a pool table in your community.”

So in We’re the Millers, dealing drugs is OK, but not dealing to minors — even an 18-year-old, which Kenny claims to be. Stripping, likewise, is OK, and Miss Aniston engages in a sizzling hot stripper’s routine to prove to one of the film’s utterly uninteresting bad guys that that’s what she is, yet she never shows more than a brief glimpse of her well-toned bottom. Most remarkably, when the family falls in with another couple (Nick Offerman and Kathryn Hahn) who want to spice up their marriage by “swinging,” it only becomes the occasion for a slightly satirical shaft directed at the hypocrisy of the mainstream culture that persecutes drug dealers (and smugglers) and disapproves of strippers. Similarly, we are introduced to Dave through a chance encounter with a college classmate — he’s been to college himself, you see, and is not just some low-life off the streets — now with a wife and children, to whom Dave gives a free sample of his wares. The last we see of the respectable classmate is when he says excitedly into his cell phone: “Great news! We’re going to get high and f*** tonight. Oh, sorry, honey. Put mommy on the phone.”

Ha ha. Clearly we are meant to share Dave’s contempt for the respectable middle class family, trying unsuccessfully to hide its vices from the children, even as we are also encouraged to see him and his partners in crime as offering us, however reluctantly and through comical misadventure, an alternative to it. Crucially, the movie’s invented family comes into existence only after its younger members have come to sexual maturity. The age of Miss Roberts’s character, a homeless runaway named Casey Mathis, is not specified, but as she is 22 in real life we are not encouraged to see her as being underage. As elsewhere, Mr Thurber and his team of writers come as close as they dare to outraging middle class sensibilities without actually doing so. The movie’s popularity, in spite of its free use of vulgarity and sexual innuendo and its relaxed attitude to the softer sort of illegal drugs, suggests that they have been successful in judging where those limits lie.

The drug smuggling is made more palatable to us not only by Dave’s being forced into it but by its being on a much larger scale than anything he expected. In addition, he is double-crossed not once but twice by the slimy Brad Gurdlinger, which allows Dave any amount of condign revenge against him without his forfeiting any of our good opinion. It also allows Dave and his instant but lovable family to stay together, once its cause for being has disappeared, in a totally unbelievable but totally satisfying way to those of us — and, surely, that means all of us? — who have been rooting for such a thing from the beginning. Maybe Jennifer Aniston’s embarrassment at the strains of “I’ll be there for yooooo!” and, by extension, the fake cosiness of “Friends,” is because at some level she knows, as does everybody else, what a silly, fantastical, impractical and implausible idea this of the reinvented family really is — the sitcom equivalent of the cartoon superhero, pretending to be nourishing fare for grownups.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.