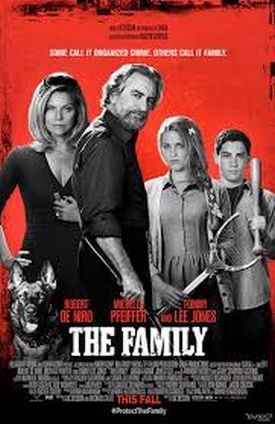

The Family

Luc Besson made a couple of pretty good or at least pretty interesting movies twenty years or so ago. They were La Femme Nikita and Leon: The Professional. You could look them up on Netflix. But, since then, whatever tether to reality those movies still had has disappeared, and M. Besson has become just another Hollywood fantasist — one belonging to the Quentin Tarantino school which regards violence as “the funnest thing you can do at the movies.” If you were to point out to either man that, in real life, violence isn’t fun at all, let alone the funnest thing you can do, he would doubtless reply, “So what? What have movies got to do with real life?” There’s no answer to that except that the question is disingenuous. Movies must reflect reality if only to the extent that they avoid it. In the case of Mr Besson’s latest film, The Family, I wonder if what is reflected isn’t a cultural turn away from Enlightenment principles towards something more primitive.

It stars Robert DeNiro and Michelle Pfeiffer as a mafia don and his wife in hiding in the fictional village of Cholong-sur-Avre in Normandy — are people in the witness protection program really settled in foreign countries? — along with their two children (Dianna Agron and John D’Leo) after he rats on one or more of his former colleagues. These notably include one Don Luchese (Stan Carp), who directs from his prison cell the indefatigable efforts of DiCicco (Jimmy Palumbo) to see that he and the family get what the Mafia thinks they deserve. Just so that we are left in no doubt about what that is, the film begins with graphic images of DiCicco’s murder of an entire family as they sit at their dinner table — perhaps because he mistakes them for “Fred Blake” (as Mr DeNiro, the former Giovanni Manzoni, is now known) and his family — before chopping off a finger of the dead paterfamilias for submission to Don Luchese.

That, plus the fact that the film is advertised as a comedy, is all you really need to know about The Family, based on the novel Malavita by Tonino Benacquista. Those wacky — and whacky — mafiosi! What a barrel of laughs! Some respect for the law and the norms of civilized society lay in the background of the old-time gangster picture, if only because its hero typically aspired, often with tragic results, to join that society. But today the romantic gangster or criminal is enjoying a new vogue at least partly because he stands outside civilized society. He is a somewhat more believable version of the superhero: not subject to ordinary law or civilized inhibition but someone who can make the petty annoyances and ordinary limitations of daily life, including those resulting from a lack of money, simply disappear. And, like the superhero, he does this mainly by using his skill at motivating others with violence or the threat of violence. The law, here in the person of an apparently emasculated Tommy Lee Jones, is an amusing irrelevance.

Mr Besson, a Frenchman himself, sets his film in France at least partly, I take it, because he wants to ensure that his audience wastes no sympathy on the locals when not just Fred but the wife and kids as well proceed to maim or even kill them for getting in their way. “Fred” actually arrives in Cholong with a body in the trunk of his car left over from the family’s previous sojourn in the south of France. Fred relies, as do other recent fictional gangsters, including Tony Soprano and Walt White of “Breaking Bad,” on our natural sympathy with the family to gloss over his appalling behavior, though The Family breaks somewhat new ground by making mom and the kids into apprentices in thuggery of whom thuggish dad can presumably be proud. Their beating up or blowing up of their neighbors, who may be parents themselves, hardly seems to matter in view of the even more appalling threat that is stalking this mom, dad and kids.

But wait! That’s not all. In addition, “Fred” decides to write his memoirs, in spite of a vocabulary consisting almost entirely of a common vulgarism for sexual intercourse, noun and verb, and half a dozen or so connecting words. As a writer, he automatically gets a further access of sympathy, even though he is a remarkably unreflective one, judging by some of the samples of his prose we are given. For example, he tells us that he got into the gangstering business because his father was a gangster before him. “I suppose I could have gone straight just to annoy him,” he writes, “but that was never going to happen.” No, indeed! He offers readers a David Letterman- style top ten list of reasons why he is really a good guy, in spite of his long criminal career. Reason number one is that he doesn’t inflict pain on others for no reason. That’s because all his sadistic urges are worked off by inflicting pain on others for a good reason.

Perhaps the most alarming thing about the movie is that Mr Besson and his co-screenwriter, Michael Caleo, seem to regard this self-justification, like the many instances of violence against the neighbors, as a funny joke. Even before the opening scene of the murdered family, the film begins with Mr DeNiro in voiceover asking: “What is a man’s life worth?” It turns out in his case it’s about $20 million. Ha ha. And you thought he was about to wax philosophical! Lest you think any satire intended against our hero’s literary ambitions, however, there is a moment in the film when he announces: “Writing is intense. I feel like I have been looking at myself in the mirror all day.” And he apologizes to his daughter: “I put you and your brother in a tricky situation, and I regret that.” She replies that he is the best father anyone could ever have.

Later Fred is also the object of the cheers and applause of the villagers of Cholong when he attends a screening of Goodfellas — a movie in which, as we do not need to be told, his real-life counterpart starred (and whose director, Martin Scorsese is an executive producer of this film) — and wins the affections of the French audience by answering questions about it, apparently without any concern for blowing his cover. One questioner asks him, “Do you meet the Mafia on the street in New York?” — a question which “Fred,” or perhaps, archly, Mr DeNiro, appears not to understand. The scene coincides with the arrival in France of DiCicco and several other goons come to kill him and the family plus, as collateral damage along with them, quite a number of the disposable neighbors.

Well, the joke’s on the villagers, of course, since they are soon to discover that you can meet the Mafia not just on the streets of New York but on the streets of Cholong-sur-Avre, and with fatal results. But in a larger sense, Mr Besson is also excusing himself for this execrable piece of work by suggesting that the Mafia and the state of Hobbesian nature in which it operates are everywhere — and everywhere inviting us to join them, if only in imagination, in that re-imagined and now delightful pre-Enlightenment world without rules or restraints upon our passions or selfish interests, where it is taken for granted that a man’s worth is measured by the size of his bank account — or his willingness to whack others in order to increase it, as Fred, pleased with himself as ever, says he has done in the end. That modern audiences seem so ready to identify themselves with the whacker rather than the whackees in such a picture is one indication of the extent to which they have been corrupted by the relentless fantasy-factory Hollywood has become.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.