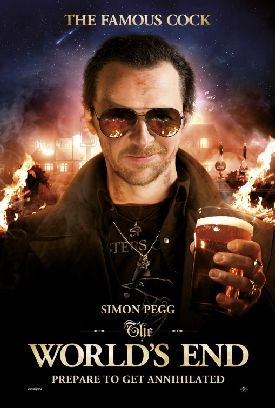

The World’s End

At one point in The World’s End, Steven Prince (Paddy Considine), aged approximately 40, finally gets around to declaring his love for his high school crush, Sam Chamberlain (Rosamund Pike). Why didn’t he say anything before? she asks him. “I don’t know,” he replies. “It just never seemed like the right time.” This was one joke the audience didn’t laugh at, or not at the showing I attended, anyway. But it wasn’t altogether clear that the director, Edgar Wright, and his co-screenwriter Simon Pegg, knew it was a joke either. Oh, they must have had a sense of it. In this, as in the two previous installments of what the pair call their “Cornetto trilogy,” Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, there are plenty of jokes about the contemporary male’s reluctance to grow up, as true in Britain as it is in America. But all three are in one degree or another ambivalent about this state of arrested development: on one level ridiculing it while on another defiantly celebrating it.

Welcome to satire, post-modern style. Recognizing that just playing around with different junk movie genres (zombie flicks in Shaun, policiers in Hot Fuzz, apocalyptic s-f here), which tend to self-parody anyway, is not enough to give their own movie a satirical direction, they introduce some big thinking in a late confrontation between Mr Pegg’s alcoholic hero, Gary King, and the “Big Lamp” who stands in for the leader of the “Blanks” or replicants who have taken the place, Invasion of the Body Snatchers style, of the good citizens of Newton Haven, England. As in Body Snatchers the replicants are all passionless, obedient citizens who stand for the sort of conformity and good behavior that the authors believe to be somehow inhuman. When the big lamp, voiced by Bill Nighy, tells Gary that their mission here has been undertaken because “Earth is the least civilized planet in the whole galaxy,” he replies that “It’s a human right to be f***-ups. . . We are the human race, and we don’t like being told what to do.”

As that appears to be more or less the moral of the story, you could call it a libertarian morality tale — as we can pretty much tell from the start it will be. Who doesn’t know what’s likely to happen when Gary organizes a reunion with four high school friends (besides Mr Considine they are Nick Frost, Martin Freeman and Eddie Marsan) in order to complete the “Golden Mile” pub crawl (twelve pints in twelve pubs in one evening) that they failed to complete at 18? I don’t think it’s giving away any surprises to say that the friends’ reminder to Gary that “We’re not teenagers anymore,” is about to be tossed around and broken apart like one of the blue-blooded replicants whose heads and limbs have a way of coming detached in the course of their frequent struggles with our heroes. It is the friends’ hard-won adulthood which is bound to be transformed in the course of the evening and not Gary’s unrepentant immaturity.

But there is a certain contradiction between the natural role of the “Blanks,” like that of the pods of Body Snatchers, as symbols of the adult responsibility and conformity that Gary has for so long been resisting and their status in the film as alien outsiders. On the one hand they are supposed to be disguising themselves as respectable citizens, which suggests that their true nature is otherwise, while on the other hand their purpose in the film is nothing more exotic or threatening than to stand for the sort of maturity and discipline that Gary has been resisting all his life. We can’t help knowing that it’s really Gary who is the alien, which is why it’s inevitable that, instead of joining the replicants’ “chain,” he will get his old pals to join him and become equally irresponsible outsiders, bent only on destruction — though we expect it to be mostly self-destruction.

Towards this end, they even have Mr Marsan’s character, Peter, meet up with someone who bullied him at school. The former bully handsomely apologizes for his long-ago behavior and says he now feels ashamed of how he treated him then — whereupon Peter proceeds to rend him limb from limb. The revenge is not his alone, but that of immaturity upon maturity for making it forsake the savage delights of childhood in favor of the reformed bully’s bland niceness. Yet the film hasn’t quite got the courage of its convictions and so merely caricatures the representatives of maturity, turning them into literally hollow men and women of no conceivable human interest to anyone.

This process is also, of course, part of the genre-satire. The point of much if not most science fiction is to provide the now politically incorrect warrior heroes of old with suitably inhuman cannon fodder which, in the absence of any acceptable human enemies (except for racists and businessmen) in our enlightened times, can be blown apart without any risk of engaging the audience’s sympathies or making the heroes look like conscienceless killers. The zombies in Shaun of the Dead fulfilled the same function. And here the replicants can even reassemble themselves from their broken pieces, or continue to walk around with missing parts, so making themselves into comic grotesques — also without offense to any actually living persons. Cartoon movies now seem to feel themselves honor bound to strive for a measure of non-cartoonish moral seriousness but, as The World’s End demonstrates once again, the nature of the cartoon itself will not permit it. At least it’s funny, however.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.