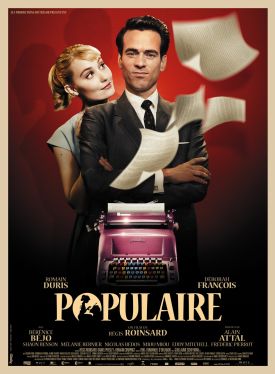

Populaire

In the Academy Award-winning The Artist, of 2011, an obscure Frenchman, Michel Hazanavicius, figured out how to recapture the magic of the old-fashioned movie romance, now all but extinct in its natural state. You simply set it in the past — that is, before the sexual revolution, which is what killed romance in the first place — and in a facsimile of the contemporary media in which audiences would have encountered it at the time. Thus, The Artist is to all intents and purposes a silent film as well as being about the silent film era and, in fact, the silent film industry. Such an immersion in its period is necessary in order to make us believe, if only for a moment, that we are seeing and feeling something like what our grandparents and great grandparents saw and felt at the time. Now another hitherto unknown Frenchman, Régis Roinsard, has repeated the trick a later era with his Populaire, which takes us right up to the brink of the 1960s, when everything changed forever. As the reviewer for Variety put it, “It’s a classic romantic-comedy setup that could have come straight from the era in which it’s set, right down to its rather naive notion that being an office assistant is somehow the apex of female self-determination.”

But of course in 1959 nobody thought being an office assistant was the apex of female self-determination. The very concept would have been as foreign to people then as the politically correct “office assistant” in place of “secretary” — whose 1950s-era sexual connotations have survived it. M. Roinsard, like M. Hazanavicius but unlike the reviewer, does not lose sight of the fact that we must know we are looking at 1959 through the eyes of 2013, even as, or especially as, he goes out of his way to heighten the 1950s effects, both cinematic and social. For me, whose memories of the 1950s are those of a young child, these begin with the evocative opening piano passage of Leroy Anderson’s “Forgotten Dreams,” which runs like a leitmotif through the film and brings back feelings of nostalgia all but inseparable from the wistful longing of the tune itself and for the world of those to whom it was originally intended to appeal.

The movie’s Pygmalion theme is also not just at home in the 1950s — as it is in the decade’s most popular musical, My Fair Lady — but is showing itself there at the last cultural moment when it was possible to do so. Rose Pamphyle (Déborah François) leaves her tiny village in Normandy to find a job as a secretary in the provincial capital of Lisieux, which she thinks of as the big city. Though an entirely self-taught, two-finger typist, she strikes her new boss, insurance man Louis Échard (Romain Duris) as a potential speed-typing champion. As a former athlete himself and a highly competitive personality, Louis determines to become her trainer and coach and take her on to fame and fortune in the speed-typing contests of the era. To that end, she takes up lodging in his decaying mansion in the country and works on learning to touch-type at lightning fast speed. “Maybe typing is your only gift,” he tells her, as if it were beneath him to notice her obvious gifts of beauty and charm — “but one gift is enough.”

The film’s awareness of its own double perspective also proves the occasion for post-modern jokes which I think it could have done just as well without. Thus, when Rose complains about his chain-smoking at the office, Louis tells her that only a law would stop him from smoking as much as he likes. Likewise, at the moment when Rose and Louis finally approach the inevitable awakening of their sexual attraction, Rose asks Louis why he thinks this is her first time — which, from what we know of her, it probably is. After all, she says to him, it’s 1959, you know! But the love scene that follows is not one that you would have expected to see in the sort of film Populaire is parodying (be warned!) and to some extent breaks through the carefully constructed framework of 1950s style and ethos.

Neither the boy-loses-girl part nor Louis’s friendship with a former American soldier, Bob (Shaun Benson), who stayed on after World War II and married Louis’s own ex-girlfriend, Marie (the luminous Bérénice Bejo of The Artist) is quite persuasively done in my view, but the typing contests, both in France and New York where national champions from all over the world come to compete for the world title, strike just the right note of absurdity and sweet suspense, echoing that of the on-again-off-again romance between this Pygmalion and his Galatea. Only in such a context could Louis get away with saying that “men and women weren’t made to get along together.” But that opinion has its ironic resonance in view of the number of critics who seem to want to see Populaire as a Mad Men-like stirring-into-consciousness of a proto-feminist Rose. For most of us, as for Mr Roinsard and his co-writers, Daniel Presley and Romain Compingt, I suspect that her considerable charm will lie rather in the movie’s having spared her the necessity of carrying any ideological banners along her route to romantic fulfilment.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.