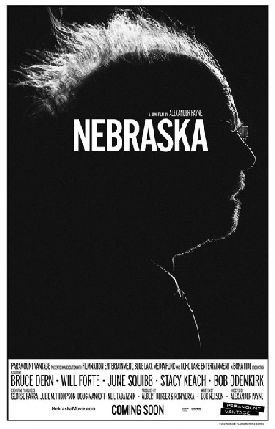

Nebraska

Everybody’s second favorite quotation from the great 20th-century British poet Philip Larkin — the favorite is obviously “They f*** you up, your mum and dad” — is the final line of “An Arundel Tomb,” and it is almost invariably quoted out of context. “What will survive of us is love” is placed in its emphatic, concluding position, I think, just in order that we may forget, for the moment, the severe, heart-breaking qualifications of the penultimate line: “Our almost-instinct almost-true.” In other words, it feels like an instinct, but it isn’t; and, in any case, it isn’t true. This is a revealing and typical rhetorical trick on Larkin’s part, but I wonder if a better, though a more banal truth doesn’t lie in a different qualification: what will survive of us is (at least some of) our “loved ones” — assuming that we have any, and that the term is understood in its fully euphemistic, funeral-directorish sense.

Love is certainly not the first word that springs to mind to describe the relationships explored in Alexander Payne’s Nebraska, but in this extended sense of loved ones as the people we are closest to in our lives — whether by choice or by accident, whether we love them, tolerate them or hate them — they and whatever it is they preserve of us are what the movie elucidates. Most of what they preserve is of course memory, which is as unreliable as people are, as love is, and the movie’s comedy depends on this unreliability of memory — both, that is, the fading memory of its verging-on-senile hero, Woody Grant, played by Bruce Dern, and the hardly less dubious memories of his family and those who knew him long ago in his home town of Hawthorne, Nebraska. But if everybody’s memories are nearly as evanescent as Woody’s, they are all anybody has.

It’s important to start off with this understanding because I think the in-built bias of so much of movie criticism tends to get the movie wrong. A.O. Scott of the New York Times, for instance, writes that “the world it depicts, a small-town America that is fading, aging and on the verge of giving up, is blighted by envy, suspicion and a general failure of good will.” Scott Foundas of Variety, thinks that “Nebraska feels, despite its present-day setting, like a eulogy for a bygone America (and American cinema), from the casting of New Hollywood fixtures Dern and Stacy Keach to its many windswept vistas of a vital agro-industrial heartland outsourced into irrelevance.” For some critics, every movie — or at least every American movie — with any pretension to seriousness has got to be about disillusionment with “The American Dream,” and all the more so when, like Nebraska or Mr Payne’s earlier films, About Schmidt of 2001 and Sideways of 2004, it is a road movie. But those movies, too, were also about much more interesting things than their geography.

Nebraska

also invites such treatment by its title, which suggests that the state is its subject rather than these particular people as people. There are matters of localized relevance — especially its portrait of the “man of few words,” stuck forever in his Lutheran-Midwestern taciturnity, but it’s not as if this is something peculiar to rural Nebraska, or has anything much to do with American dreaming. I, too, am disillusioned with the American dream, but only in the sense that I think the concept has ceased to have any meaning — that’s if it ever did have any meaning to begin with. It’s just lazy critical shorthand for the utopia, whether of the past or of the future, that every serious artist is assumed to believe in and to be bitter about the non-existence of. There are, to be sure, lots of movies which fit this critical template, since it is obviously the way to appeal to the critics, but they are nearly all pretentious and boring. And Nebraska is not one of them.

As if deliberately to tempt the formulaic critics, however, Mr Payne puts his plot in motion with the help of a typical bit of American commercial charlatanism, a junk-mail communication from a Publishers’ Clearing House-type operation in Lincoln, Nebraska, which makes Woody Grant think he has won a million dollars. An alcoholic banned from driving and so determined to walk from Billings, Montana, where he lives, to Lincoln to claim his money, Woody is obviously a bit confused, but as someone tells us later in the film, he has always been a bit confused. There is also a wryly American touch about the fact that Woody doesn’t trust the postal service — the government, as he presumably sees it — with his supposedly prize-winning missive even as he trusts implicitly the scam- merchants who sent the thing in the first place. “They can’t say it if it isn’t true,” he says to his son. This seems to be the one moral certainty that still lingers in his ravaged brain.

But having said the few lines Bob Nelson’s script gives her to say on Mr Payne’s stage, America proceeds to fall silent for the rest of the film, remaining there only in the form of Phedon Papamichael’s mute monochrome tributes to the forbidding Nebraska prairie and the lowering skies above it. And a good thing, too. I nearly always find that America is better seen than heard from in the movies. Instead of confining itself to anything as narrow as whole country, this one focuses our attention on the universal aspects of Americana as Woody, now too unreliable a witness to his own life, is seen through the eyes of his wife, Kate (June Squibb), his younger son, David (Will Forte) and various friends and relations back in Hawthorne. There, as if by chance, he and David stop on their way from Billings to the emerald city of Lincoln after David, whose own life is at something of a dead end, agrees to drive his father there in order to humor him.

Or something. David’s decision to drop everything and undertake this journey with his half-crazy parent is one of the weaker spots in Mr Nelson’s plot, like the defining but distracting sexual assault conviction of David’s doltish cousin Cole (Devin Ratray), though less obtrusively so. The former is structural, but it is an implausibility worth swallowing, along with the subsequent implausibility of the arrival in Hawthorne of Kate and David’s older brother (Bob Odenkirk), a TV news reader, because of the comedic riches it yields. And here we require another word of caution over the critical temptation to see, as at least one observer does, Kate’s running commentary on the past of Woody and his family as “unmerciful but decidedly honest.” Unless we recognize that she, every bit as much as Woody and the folks back in Hawthorne, has mentally remolded the now-extinct realities of her life according to her own self-mythology we will miss the true poignancy and even much of the humor of Woody’s story.

For the film itself is “unmerciful” about him, as it is about all of its characters, very much including Kate. All are weighed in the balance and found wanting — or all except, as a sort of joke, Peg Bender (Angela McEwan), the widowed proprietor of The Hawthorne Republican who is an old flame of Woody’s, and a couple real Nebraskans, the Westendorfs (Eula and Neal Freudenburg) whom Kate surprises us by having nothing bad to say about. David is the film’s most sympathetic character, but he is too much of a sad sack, a literary naif for whose benefit everybody else is putting on this show of what human life amounts to to be a real exception. He, too, is trapped in the prison of self apart from the moment of insight (or whatever it is) that leads him on this tragi-comic journey to find what love really is. It wouldn’t do for David to be seen as too much better than his old man.

For there is more than a hint here, too, of that other Larkin line about being f***ed up by your mum and dad. Also as in the poem, there an implied comparison between child and parent, especially when Peg Bender tells David that she remembers Woody as “a kind man” who “couldn’t say no to a favor.” To me this moment in the film is as unbearably touching as the effigies of the earl and countess holding hands on the Arundel tomb was to Larkin. Like him, we have to guard against deceiving ourselves that love, or what we see of it anyway, can be definitional. It’s certainly not the whole story about Woody or anyone else in the film, any more than it is (we assume) of the earl and countess. But in a movie about unreliable memories and unreliable people it stands out as a glimpse of possibility: the possibility of something real and permanent. For this moment and one or two others we can believe that love lasts when all else has faded or turned to sadness and disappointment — and that you don’t have to be a perfect person, or even a likable one, in order to be touched by its grace.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.