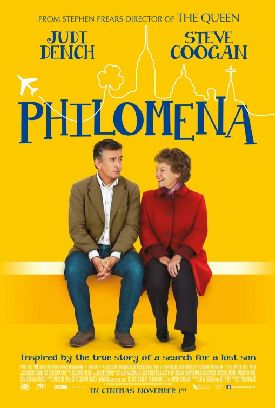

Philomena

You may find that you have, as I do, a slight problem with Stephen Frears’s Philomena, which is in many ways — chief among them the fine performance of Dame Judi Dench in the title role — a lovely and a touching film about a mother’s search for her lost child 50 years after being forced to give him up for adoption by the sisters of an Irish convent who had taken her in. The problem can be summed up in the words of Martin Sixsmith, who wrote the true-life “human interest” tale on which it was based at the urging of the true-life Philomena. Writing in The Daily Telegraph, he notes that her secret, kept from even those closest to her until she finally decided to reveal it, was that she “had been a teenage single mother in Ireland at a time when sex outside marriage was considered a sin.” Believe it or not, Martin, it still is considered a sin. It’s just that, nowadays, neither the Church nor anybody else appears to think that this particular sin is anything to get very upset about.

Obviously, that was not the case in 1952, but the change in social norms flatters Mr Sixsmith’s unconscious assumption of moral superiority. That is, like most progressive-minded folk, he assumes that, as time has gone by, we have learned that right and wrong are not what we thought they were a generation or two ago. In many cases they are the opposite of what we thought they were. And those who lived in those benighted days can only be condemned for their failure to be as virtuous and enlightened as we are. Mr Frears and the other film-makers behind Philomena — including Mr Sixsmith and Steve Coogan, who plays him in the film and who co-wrote the screenplay with Jeff Pope — thus align themselves with the kind of secular moralists of today who are outraged by the treatment the Catholic Church once gave to single mothers and their babies but are entirely unperturbed by the millions of abortions that are our own way of dealing with the same problem.

As you would expect, therefore, the film is informed by a skeptical, secular, anti-clerical morality from whose commanding height of certainty it rains down hostility towards the Church and condescension towards its principal character. Mr Sixsmith describes Philomena to his wife as an example of “what a steady diet of Reader’s Digest, The Daily Mail and romantic fiction will do to the human brain.” Such simplicity can hardly be unrelated to her portrayal as a faithful daughter of the Church in spite of her abuse at its hands. That she was abused, we must accept, if only so that we may appreciate the act of forgiveness which is the film’s best moment. But the indignation on her behalf of the film-makers insulates them from the need to look with any degree of skepticism or detachment at their own point of view on the whole matter, which is clearly the same coming out as it was going in. There is, it’s true, a half-hearted attempt to reprove Sixsmith-Coogan’s anger against the nuns with Philomena’s forgiveness, but the movie itself has none of her forgiving spirit behind it.

All the emotion here has been carefully turned in one direction: that of the longing of the mother for her lost child whom Mr Sixsmith, an unemployed journalist, undertakes to help her find. I cannot say much more about the movie’s plot without giving away what people would consider to be “spoilers,” but the child was adopted by an American couple — as Philomena knew when it was taken away from her at age three — and that suggests that there must have been certain emotional cross-currents in connection with the child’s relationship to his adoptive parents which the movie is at some pains to exclude. The only indication that the child’s other parents might have had some feelings worth considering comes with a single reference to the fact that the adoptive father could be a hard man at times and the apparently real home movies of the boy’s childhood in America which punctuate the later phases of Philomena.

We also know that the grown man wanted very much to find his biological mother in a way that suggests a degree of estrangement from the adoptive parents. We also know that he is put off in his quest by the same lie that the nuns tell to Philomena: that the records were destroyed in a fire. But the evidence of his continued strong attachment to a woman (and, incidentally, to a country) he can hardly have remembered, while consoling to Philomena could easily have been at least as painful to the people who loved him and brought him up in America as his having been taken away from her in Ireland all those years ago was to Philomena. However, about all that side of things the movie — which is in any case more interested in the odd-couple pairing of the journalist and the credulous old lady than it is in the object of their quest — doesn’t know and doesn’t want to know.

At the moment when Philomena forgives the nuns, Mr Coogan’s Martin Sixsmith turns his anger on her. “Just like that!” he says to her, outraged, now, at her for being incapable of his own hatred towards them.

“No!” she says firmly. “Not ‘just like that.’ It’s hard for me, Martin.”

As, indeed, we can well imagine it must be. But there is a certain air of “just like that” about the movie itself, a sense of its having simplified moral and emotional (to say nothing of religious) matters that deserve more searching and sensitive treatment than they are given here. It’s all good guys and bad guys — though the bad guys, though no less bad for that, are let off any well-deserved punishment. It is a simplistic moral model which, admittedly, commercial movies tend to thrive on. But that’s no more an excuse for them than the ruthless enforcement of the social standards intended to uphold the Church’s teachings about sexual morality was an excuse for the cruelty and deceit of the nuns.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.