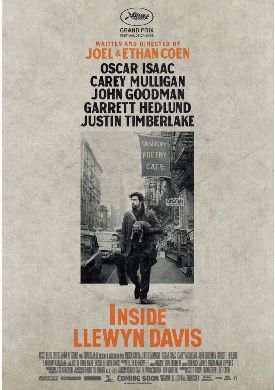

Inside Llewyn Davis

You know how, sometimes, when somebody says something really funny or clever and you want to tell somebody else about it but you can’t quite remember the exact words or what it was in the context that made it so funny or clever? Anyway, when you say it, it doesn’t sound so clever or funny as when the funny or clever person said it, and you add, rather lamely, “You sort of had to be there”? Well, some such form of words as that ought to have been appended by the Coen brothers to their new movie, Inside Llewyn Davis. They seem to have been counting instead on an audience that was there, or at least that thinks it was there or wishes it had been there, and so is willing to come more than halfway to meet them in their half-hearted attempt to recreate the alleged magic of Greenwich Village in 1961. But for those who aren’t folkie or media-culture wannabes, it’s a local-interest story for America’s media capital, and it doesn’t, as they say in the business, travel very well.

To me, the most interesting thing about the movie is the complete excision from it of any political element. The story, as the Coens admit, is loosely based on that of musician Dave Van Ronk, who was politically a sort of leftover from the 1930s Popular Front days, being both socialist and anarchist — it somehow must have made sense at the time — and an actual life member of the IWW or “Wobblies.” Who knew they were still around? Like most of his crowd, he wore his politics on his sleeve, but the Coens’ hero, Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac), apparently has no politics. That would normally be a good thing, but in his case the omission becomes the dog that didn’t bark: a presence on account of its absence. Llewyn is just a hang-dog merchant mariner who fancies himself as a folk-singer and who, in the movie, is not quite making a living at it. In other words, we are meant to see him as a classic American little-guy striver instead of a would-be Woody Guthrie or Pete Seeger, bringing the revolution to “capitalist” America one song at a time.

Unfortunately, even before F. Murray Abraham’s club owner pronounces his definitive doom on the poor guy’s aspirations — “I don’t see a lot of money here” — we cannot but be aware that he is bound not for glory but for the musical damnation of “niche” status. The politics is the only thing that could have tied him to a more general interest of the period as it really was. Presumably there was a commercial calculation behind the Coens’ attempt to sanitize this slice of recent American history, since people might find difficult to participate in nostalgic feelings for the youthful idealism of the 1960s if it were still attached to the naive leftism that was, really, pretty much inseparable from it. Young people today, of course, don’t know about that, but I imagine even they will sense something is missing here. Van Ronk without his politics isn’t really Van Ronk. He isn’t really anybody.

Perhaps the Coens were betting that it was the politics, at least in part, which prevented him from being as big as the more politically cagey Bob Dylan — the back of whose curly head in an entirely incidental and unremarked moment as he sings a couple of bars in his trademark gravelly voice is all there is in the movie to remind us of the possibilities of artistic success greater than that of its pathetic antihero. For of course it would not be hip — to use a word dating from approximately the same time and place — to make an old-fashioned biopic about a musical success story. Failure is also a necessary part of the movie they have made, the point of which, like that of the “existential” works so popular at the time, is that there is no point, no classic character arc, but just a vicious if often rather amusing cycle of failure and futility.

Noble failure — like but apparently unrelated to the failure of socialist idealism — must have been intended to set off the music as the justification both for the movie and for its hero’s otherwise futile existence, but the music just isn’t that good either. Even I, who have no nostalgic feelings for the time and place, wanted to like the movie for the sake of the music. Regrettably, although Mr Isaac has a perfectly serviceable voice, he manages to make it all too clear why this music, like the politics of most of those who made it, was never taken to the heart of the masses — and why, therefore, it has since become the property of those musical antiquarians who come in for a bit of rough handling in the movie.

Joel and Ethan Coen are the village atheists of American cinema. Here, as in No Country for Old Men, they first and foremost mean to tell us that, no, the world is not like the movies. They take to the movies themselves to tell us this and so, like others of the new atheists, make a religion of their irreligion. But why should we need to be told that life is a meaningless striving that leads to nothing and ends in death? Is there some danger in allowing ourselves to forget this for a moment and finding something to be hopeful about? Their relentless negativity was relieved for a moment almost two decades ago in Fargo by the sympathetic portrait of the pregnant police-chief and her duck-painting husband, Norm. For once the brothers allowed themselves to confer a kind of benediction on the normal American middle, with all its quirks and quaint beliefs about goodness and God and success. Perhaps this so horrified them that they are still reacting against it. Interestingly, there is a pregnancy here, too: one which Llewyn has paid to have aborted and which, to his surprise, he learns was not aborted. The girl, who never appears on screen, has returned, alone, from the Metropolis to Akron in good old middle America to have the baby, who must by now be a toddler. We see Llewyn driving past Akron in the dead of night, in the snow. He doesn’t stop. The renewal of life and love and hope are not for him any more than they are, now, for his creators — or those for whom they continue to make their movies.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.