Liberal 2.0

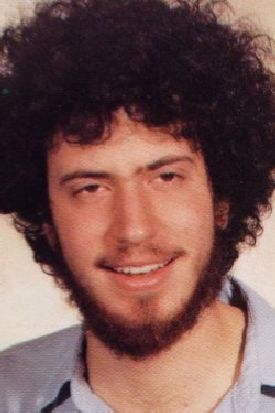

From The New CriterionBill de Blasio in Sandinista mode

For the political left in America, the end of the year brought good news and bad news. The good news was that the election of Bill de Blasio as mayor of New York seemed to promise a new era of progressive success both in the city’s government and at the polls elsewhere — a left turn for the nation and not just the Big Apple. The bad news was of course the fiasco of Obamacare, though that didn’t seem too bad so long as you could persuade yourself, as the media generally did, that it was just a matter of a temporarily buggy website and not a permanently unworkable system. Persuading the nation of the same thing was naturally a job for the ever-reliable New York Times, whose Sunday Edition on December 1st featured a breathless, 5000-word account of what it represented as a heroic rescue effort by President Obama and a crack team of his closest advisers of the Affordable Care Act:

As a small coterie of grim-faced advisers shuffled into the Oval Office on the evening of Oct. 15, President Obama’s chief domestic accomplishment was falling apart 24 miles away, at a bustling high-tech data center in suburban Virginia. HealthCare.gov, the $630 million online insurance marketplace, was a disaster after it went live on Oct. 1, with a roster of engineering repairs that would eventually swell to more than 600 items. The private contractors who built it were pointing fingers at one another. And inside the White House, after initially saying too much traffic was to blame, Mr. Obama’s closest confidants had few good answers. The political dangers were clear to everyone in the room: Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr.; Kathleen Sebelius, the health secretary; Marilyn Tavenner, the Medicare chief; Denis McDonough, the chief of staff; Todd Park, the chief technology officer; and others. For 90 excruciating minutes, a furious and frustrated president peppered his team with questions, drilling into the arcane minutiae of web design as he struggled to understand the scope of a crisis that suddenly threatened his presidency. “We created this problem we didn’t need to create,” Mr. Obama said, according to one adviser who, like several interviewed, insisted on anonymity to share details of the private session. “And it’s of our own doing, and it’s our most important initiative.” Out of that tense Oval Office meeting grew a frantic effort aimed at rescuing not only the insurance portal and Mr. Obama’s credibility, but also the Democratic philosophy that an activist government can solve big, complex social problems. Today, that rescue effort is far from complete.

And far from complete it was likely to remain for some time to come, too, though the dashingly dramatic yet absurdly detailed narrative style of Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Michael D. Shear — who even managed to get the Vice President’s middle initial and his vestigial “Jr.” in — was familiar enough for us to know how and where the story arc was supposed to end. There was even an administration “war room” out in Columbia, Maryland, for heavens’ sake! There, on “the fourth floor of a nondescript office building that sits next to a shopping mall, close enough for frequent food runs to Chick-fil-A or Five Guys Burgers and Fries,” the fix would happen “or not at all.” Surely, if we know anything about media story-telling, those excruciating minutes, that furious and frustrated president peppering his underlings with questions, those capitalized Burgers and Fries, that frantic but brave rescue effort could have only one end.

And, indeed, on the same day the article appeared, the White House announced that the website had been fixed just in time to meet its self-imposed deadline. Or at least (which must amount to the same thing) “that it works well for the vast majority of users” — even though much remained to be done. That part, the undone bit, was understood to include the 30 to 40 per cent of the website known as “the back end” which, taking place in the decent obscurity of cyberspace, was needed to complete the connection of individual users with insurance companies and which the administration itself acknowledged had yet to be built. The synecdoche might have seemed to some irresistible: Obamacare amounted to a vast Potemkin village which only existed as the parts the public could see.

Thus it was with some audacity that Ms Stolberg and Mr Shear acknowledged in the passage above that not only the fate of HealthCare.gov was at stake but that of what Walter Russell Mead calls “the Blue Model,” or (as they put it) “the Democratic philosophy that an activist government can solve big, complex social problems” — in practice by the lavish spending of borrowed money. Hadn’t the Republicans who opposed the Affordable Care Act root and branch been saying similar things from the beginning? Could there be a hint here that there lingered the faintest of doubts in some administration minds as to whether or not they mightn’t have had a point? But if, as Professor Mead writes, the “failure of the Blue Model” is the central political datum of our time, readers of The New York Times must be blissfully unaware of the fact. The answer to that strictly rhetorical question about the “Democratic philosophy” and the powers of big government to solve complex social problems lies in the Stolberg-Shear narrative itself. Surely those exciting scenes of heroic bureaucrats and technicians swinging into action to save the President’s “legacy” must put to rest any such doubts. What can such men and women not do?

The media coverage generally followed the pattern laid out by the Times in concentrating on the website’s problems — which stood a better chance of being “fixed” than the Affordable Care Act itself — as a way of ignoring the much larger problems of trust (“If you like your plan you can keep it”), cost (the pretense of greater “affordability” of newer policies by comparison with older ones was quietly dropped on the grounds that the old, cheaper ones were worthless anyway) and the more general unpopularity arising out of the fact that people were being forced to buy coverage they didn’t want or need. Meanwhile, the President embarked on a public relations blitzkrieg in which he attempted to obscure the same public dissatisfactions by linking the Affordable Care Act to other administration desiderata, including raising the minimum wage and redistributing income, which the health care law was implicitly acknowledged to have as one of its purposes.

Only a few days earlier, the Times itself had reported that

These days the word [sc “redistribution”] is particularly toxic at the White House, where it has been hidden away to make the Affordable Care Act more palatable to the public and less a target for Republicans, who have long accused Democrats of seeking “socialized medicine.” But the redistribution of wealth has always been a central feature of the law and lies at the heart of the insurance market disruptions driving political attacks this fall.

But two days after the highly dubious announcement that the website’s technical problems had been fixed, Jackie Calmes of the Times reported,

President Obama left the White House on Wednesday for one of the capital’s working-class neighborhoods to talk about the economy, not simply to divert attention from the troubles of his Affordable Care Act but also to explain how that law, for all of its flaws, fits into his vision for Americans’ economic security and upward mobility.

As a connoisseur of political apologetics, I admire the heck out of that “simply,” which I didn’t even notice until I had read the piece through a second time. Ms Calmes also suggests that “upward mobility” — along with the “inequality” that supposedly results from a lack of it — is a stand-in for “redistribution,” since, as the context made clear, the President was referring not to opportunities for significant numbers of individuals to rise in the income scale by ambition and hard work into more high-paying employment (the traditional meaning of the term as it is understood by most Americans) but to a general, government-mandated increase in income and benefits for everyone in the poorer segment of society. The media naturally failed to notice any change in meaning — in the same way, perhaps, that Ms Calmes refers to Anacostia as a “working-class neighborhood,” since its 35 per cent unemployment rate suggests that it might be more accurately described as a non-working class neighborhood.

But the real partnership between journalist and president is revealed in Ms Calmes’s treatment of the President’s speech in Anacostia as if he were simply promoting mainstream measures that have always been there in the Democratic repertoire — and, indeed, the Republican one:

That vision — of an economic partnership between government and its citizens — is one that Mr. Obama has described since he was a state senator in Illinois, and it draws on the legacies of three Republican presidents: Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and Dwight D. Eisenhower. On Wednesday, he reiterated the policies required to carry it out, even though it has long been clear the opposition from Republicans is likely to make many of them unattainable. “It’s true that government cannot prevent all of the downsides of the technological change and global competition,” the president said. “But,” he added, “we’ve also seen how government action time and again can make an enormous difference in increasing opportunity and bolstering ladders into the middle class.”

Not only are we living in Obama-land, we have always been living in Obama-land without even knowing it. “The policies required to carry it out” supposedly “reiterated” by the president were not, however, “ladders into the middle class” (always assuming that these could be “bolstered”), nor were they those of any of the presidents mentioned in the Times’s account of it. They were, instead, the Affordable Care Act, now being sold as a route to “social mobility,” an increase in the minimum wage and further expansion of the already much-expanded food stamps program. Republicans might be making such things unattainable, as the article acknowledged, but the important thing was to make it clear that their purpose was the same as that of the much reviled Affordable Care Act — which the GOP were also attempting to interfere with — and that all were solidly in the mainstream tradition of American politics.

The media’s willingness to come to Mr Obama’s aid in this public relations offensive may have been due to more than just their habitual championing of him and his administration. The election of Mr de Blasio in New York seemed to many to herald a bright new dawn of progressive politics, both in the city and in the country as a whole where, within days of his election, The New Republic was touting the presidential prospects in 2016 of Elizabeth Warren, the soi-disant “Native American” and equally liberal senator from Massachusetts. “Hillary’s Nightmare?” headlined a cover piece by Noam Scheiber. “A Democratic Party That Realizes Its Soul Lies With Elizabeth Warren.” A week earlier most people might have thought that the Democratic Party’s nightmare, but suddenly anything seemed possible.

One interesting thing about the media’s coverage of Mr DeBlasio’s triumph was the rehabilitation of the word “liberal” — not, of course, to mean liberal, which it hasn’t done for three quarters of a century or more, but to mean what has lately and much more often come to be called “progressive.” The New York Times headlined “New York’s Next Mayor, an Audacious Liberal” and noted “the decidedly liberal worldview that has been the hallmark of his career.” Evidence for this included the fact that, when as a young man he went to Nicaragua as a protest against “American intervention” there, “Mr. de Blasio got a glimpse of the possibilities of an unabashedly liberal society, with broad access to health care, literacy and property.” Presumably the property, like the literacy and the health care would be supplied free by the government in an “unabashedly liberal” polity. “But,” continued the Times reporter, the new mayor “felt the ruling Sandinista government of Nicaragua could be too controlling, and he hungered for a role in shaping politics closer to home.” Ah, yes: the eternal “liberal” chimera of a redistribution of “wealth” (or “property”) which is, at the same time, not “too controlling.” That must also have been what he sought by “shaping politics” back in his home town of New York.

Even across the Atlantic, the Daily Telegraph of London headlined “Bill de Blasio: unapologetic liberal becomes first Democratic mayor of New York for almost 25 years,” while The Independent noted that “de Blasio ushers New York into a brave new world of liberal governance.” It was almost as if it were now “progressive” which had become suspect and “liberal” the euphemism. Or are we to suppose that “liberal” is the preferred term for what we might call the Sandinista wing of the progressive movement? The “unapologetic” part of his liberalism was at least a challenge to those who still regard the term as electoral poison. Haven’t they heard? Liberalism is now the mainstream — which, when you think of it, is just the corollary of the now familiar trope of media-speak that conservatism has grown “extremist.” The one implies the other, and the election of Mr de Blasio provided a fillip to the media’s natural tendency to write in such terms.

This, it seems, is what is meant by progressivism. The whole political culture progresses leftwards and leaves behind those who don’t move with it, clinging to beliefs that (they seem to remember) were mainstream only a few years ago but are now the province of bigots, kooks and extremists. During congressional debates over Obamacare, as I noted at the time (see, for example, “It’s Only Common Sense” in The New Criterion of January, 2010), the proponents of the measure were fond of talking about it as putting themselves “on the right side of history” — and their opponents, therefore, on the wrong side. To some extent, given how close the ACA came to being defeated like its “Hillarycare” predecessor 17-years earlier, this must have been whistling past the graveyard on the part of the left. But now the euphoria of the de Blasio election and the wishfully “fixed” Obamacare website must have come together to make them think they were right all along and that the shifting tides of “history” had indeed marooned their opponents on the wrong side of the mainstream. That must also be why the media almost never questioned the President’s often reiterated yet patently false contention that the Republicans had only opposed or “obstructed” the new health care law without ever saying what they would put in its place. There were actually several Republican alternatives, most recently that proposed by Ramesh Ponnuru and my Ethics and Public Policy colleague Yuval Levin. But if you’re on the wrong side of history, apparently, no one on the right side can hear you.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.