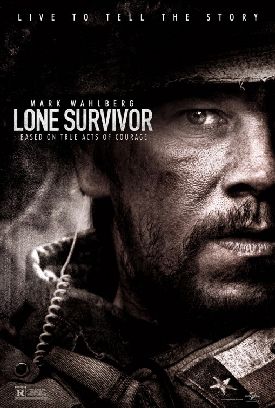

Lone Survivor

After only six weeks in release, Lone Survivor is closing in on the box office record set last year by Zero Dark Thirty for movies about our post-9/11 wars. Yet it has received little publicity compared not just with Kathryn Bigelow’s film, which courted controversy with scenes of torture that portrayed the torturers sympathetically, but also with the string of anti-war flops that came before it. Hollywood and the media desperately wanted people to like those movies for the sake of their political agenda, but people didn’t like them and didn’t go to see them. Zero Dark Thirty at least looked to people like it was pro-American. Lone Survivor, directed by Peter Berg, has carefully removed the (allegedly “right-wing”) politics in the true-life account by the actual lone survivor, Marcus Luttrell (played in the movie by Mark Wahlberg), of a Navy SEAL operation in Afghanistan in 2005 that went badly wrong, and people are flocking to it. The critics and the media generally have taken a somewhat more sour view, sometimes supplying their own political subtext out of frustration with Mr Berg’s reticence. Richard Corliss’s clueless review in Time was headlined: “Why Are We in Afghanistan?”

The movie itself is the best argument for regarding that question as supremely irrelevant from the point of view of the SEALs and those, still the majority of Americans, who identify themselves with such brave men rather than the intellectually stateless moralists. Ever since the media and the film industry were captured by the anti-war movement during the Vietnam era, it has been almost impossible for us to see war in the movies or on television as combat soldiers see it, which is with more or less complete disregard for the political or diplomatic side of things, except where that prevents them, as increasingly it does, from doing their job. Mr Berg’s great achievement in Lone Survivor — equaled only, perhaps, by Ridley Scott in Black Hawk Down (2001) — is to take away the media’s political filter and show us war as men actually experience it, albeit at an unusually high level of intensity.

Even more admirably, he is at the same time able to include a moral problem of warfare of a kind likely to be encountered by combat troops, as it actually was by the men in Mr Luttrell’s memoir, and not the remote, theoretical kind of moralizing soul-searching that the politicized media would clearly have preferred. This problem arises when the four SEALs, dropped onto an Afghan mountaintop to provide intelligence about the supposed presence of a warlord in the vicinity, are spotted by three goat-herds: an old man, a young man and a boy. The Americans know that the Afghans are Taliban sympathizers and that, if they are allowed to proceed on their way, they will advertise their presence to the much more numerous Taliban fighters in the area. They can save their own lives by killing the Afghans, but after some debate they conclude that doing so would not be consistent with “who we are.” Though they know it means almost certain death for themselves, they let them go.

The debate is a realistic one. The moral consideration is important to the men, but what finally sways them is the shame of killing civilians, especially a child, should it be discovered and advertised to the world on CNN — as they can realistically expect it would be, thanks to the temperamentally anti-war and scandal-loving American media. The movie doesn’t dwell on this consideration or engage in any polemics at the expense of the media, as Mr Luttrell’s book does, and the rest of the film is a straightforward account of the heroism of the four in their battle against overwhelmingly superior forces, resulting in the sad situation foreshadowed by the title. Near the end there is another moral crux, or at least a potential one, where the lone survivor is protected by Afghan villagers bound by the Pashtun code of hospitality to protect a guest from his enemies.

It is a flaw that we only learn of this code from a card on the screen at the end instead of seeing it worked into the main body of the film as a symmetrical point of Afghan honor — and also costing some of the lives of those who observe it — matching that of the Americans with the goat-herds. I understand why he does it: to make our experience of the helpful villagers as uncomprehending as that of Mr Wahlberg’s character. But the thematic point would have helped to humanize the Afghans. I would also have liked to see more of the SEALS before the mission than the footage of training shown at the beginning. The guys don’t have enough of a chance to be guys before they became heroes, so that their heroism is harder for us to see as the picture of reality it in fact is. The documentary-style scenes of SEAL training exercises further stress the main characters’ remoteness from the ordinary life of our common humanity. But these are not serious faults in a context that is otherwise very realistic, as the number of military technical advisers suggests the movie sets out to be. Mr Berg has produced a film that I expect to become a classic American war movie — though I don’t expect the media will like it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.