Casualties of War

From The Weekly StandardWounded: A New History of the Western Front in World War I

Emily Mayhew Hardcover: 285 pages, Oxford University Press, USA

If you read only one book this year to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War, let me suggest Wounded rather than one of the more conventional histories.

The virtue of this choice is that it is likely to give you a better idea both of what the war was actually like for those who experienced it—hint: somewhere in between the great and glorious adventure we all now know it wasn’t and the unremitting horror we all now know it was—and of why it still looms so large in the culture and the moral consciousness of the Western world a century later. In some ways, it marks even more of a watershed than World War II, whose moral import in the popular mind has been reduced to something it hardly seemed at all to be at the time, namely a sort of Armageddon for cultures based on racism and ethnocentrism, and a beginning of the world anew.

Both wars now appear in hindsight through the lens of the pacifist culture of the academy and the media, who are, like President Obama, opposed in theory not to all wars but only to “dumb” ones (yet they tend to have a hard time thinking of any wars that are not dumb). It is surely not an insignificant datum that hardly anybody in the combatant nations during World War I thought that the war, now the very model of the dumb war, was dumb at all. They who actually experienced the horror of it, bar a few now well-known names, seem to have thought it less horrible than we do at a century’s distance in time.

Not the least of the virtues of this fascinating volume is that it suggests some of the reasons why this may be so. Emily Mayhew, a research associate at Imperial College, London, only set out to tell the story of the British Royal Army Medical Corps and ancillary operations in the 1914-18 war — something not often treated in secondary material up until now. She pulls together, in one place, accounts of the wounded and those who tended to them that are not always readily available to readers, supplemented with archival research into primary sources: letters, memoirs, and journals. The results are inspiring and often deeply moving.

Perhaps her most surprising finding is that, in a war now famous for military blunders, particularly British ones—the phrase attributed to Erich Ludendorff, “lions led by donkeys,” may be the most quoted judgment on the British effort in Britain itself, as well as the most unjust — the treatment of the wounded should be seen as a great success, at least as it compared with anything known in previous wars. This was the result of “an unconventional yet crucial medical breakthrough: the discovery that surgery could be done in a forward medical unit close to the actual place of wounding, and that by doing so survival rates would be radically improved.” Referring to the new Casualty Clearing Stations, where such surgery was performed, Mayhew writes, “By 1918 the CCS system in France had been refined into an extraordinary medical machine. During battle its doctors and surgeons did work of unprecedented complexity and effectiveness. Every medic in the country wanted to be part of it.”

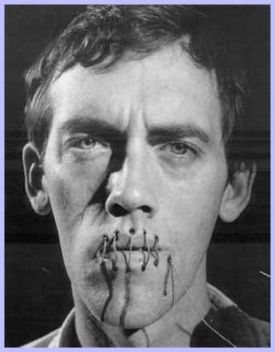

A case could be made that the postwar predisposition, lingering on into the present day, to see the war as uniquely horrifying was, in part, a product of that success, since more of the wounded survived than in any previous war to serve as living reminders of its terrible cost, often for decades after it ended. One such survivor was John Glubb — later to become Glubb Pasha, founder of the Arab Legion — whose wound to the jaw and face led to his becoming known in Jordan as abu Hunaik, or the one with the little jaw, and the treatment of his wound is described here. Glubb was particularly well-qualified to note that “the real horrors of war were to be seen in the hospitals, not on the battlefield.”

Wounded also makes clear the extent to which the Great War was a war of the middle class and of what used to be called the respectable working class—again, by comparison with previous wars. Wellington’s “scum of the earth” had been gentrified in the course of the 19th century, and, like their doctors, they knew the virtues of respectability, including cleanliness. Nurses were employed to do endless amounts of laundry, among their many other duties at the front.

There was so much laundry to do, with some men needing a change of bedclothes several times a day, that it could be disheartening. But then the nurses remembered how much their patients appreciated the luxury of clean linen—a fresh sheet, a white pillow case, fluffed blankets—so they scrubbed and pegged and folded, understanding that this too was an act of nursing and healing.

Their dedication and, indeed, heroism adds a new dimension to the more familiar story of the bravery and sacrifice of the combatants.

Many will find the best things about this book to be its stories of courage, devotion to duty, and self-sacrifice on the part of the doctors, nurses, orderlies, stretcher-bearers, ambulance drivers, and others—most notably chaplains, who very often threw themselves into assisting with the medical tasks of hospitals and dressing stations as well as attending to spiritual tasks. One such, a Roman Catholic priest, took it upon himself to, in addition to his normal duties, go out into no- man’s-land at night to bury the dead who had fallen in the field, all while under fire himself. Those who noted the absence of God from the trenches were presumably not looking in the right places.

We also learn of the new interest of doctors in mental casualties—though these were always kept separate from the rest at the Casualty Clearing Stations and hospitals, and even on the ambulance trains, where they were kept in separate carriages for the sake of morale: “All over the front RMOs [Royal Medical Officers] were coming to find this class of patient increasingly interesting. For some of them the treatment was quite simple: when the sound of the guns drew nearer and the patients became increasingly upset, the staff went round the ward putting cotton wool in their ears to muffle the noise and restore calm.”

There were also moments of humor, as there were in the trenches. Major Alfred Hardwick of the 59th Field Ambulance unit took advantage of a two-week leave in England to bring back a couple of ferrets from his home in the West Country. They were brilliantly successful at killing trench rats, with which his section of the front had been plagued, and the men were very grateful.

On Hardwick’s birthday they celebrated with red wine, games of poker and organized ratting, with each kill being celebrated with increasingly drunken cheers and songs about the only two creatures who really enjoyed themselves on the Western Front. What would the ferrets do, the men wondered, if the war ever ended? How could they ever go back to a Cornish farm, now that they had hunted for trench rats in France?

In the words of the old song: How ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm? In the case of the men, if not the ferrets, the answer was that you wouldn’t. A new world — recognizably our world — emerged from the Great War. And Wounded goes a long way toward explaining why it did.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.