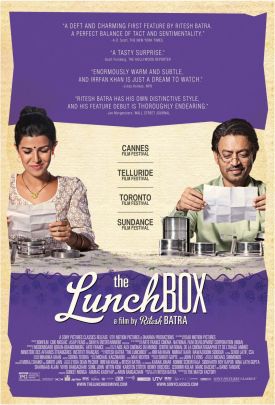

Lunchbox, The

The word for “lunchbox” in Hindi is dabba, and the people who deliver lunchboxes, mostly from their wives at home to husbands working in the ever-growing office population of Bombay — which the politically correct are now commanded to re-name “Mumbai” — are called dabbawallahs. As we are reminded in Dabba or The Lunchbox, directed by Ritesh Batra from his own screenplay, the system devised by the dabbawallahs for getting the right lunchbox to the right recipient is world-famous for not making mistakes in spite of its not being the product of modern electronic information-management. Why, their system has been studied by Harvard University, as her dabbawallah (Sadashiv Kondaji Pokarkar) proudly informs lonely housewife Ila (Nimrat Kaur) when she complains that he has been taking the lunchbox she prepares every day to a man who is not her husband. He is sure he could not have made the mistake she and we know he has made.

This is a vital piece of information in the film because it is against the background of the supposed infallibility of the system that both Ila and Saajan Fernandes (Irrfan Khan), the sad widower who is receiving her husband’s lunchboxes, gradually come to see the mistake as no mistake at all. As the puppyish Shaikh (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), Saajan’s young protégé and designated successor at the company from which he is about to retire, quotes his mother as saying, “Sometimes the wrong train will get you to the right station.” That Shaikh, an orphan, treats his mother as being still alive and continuing to dispense wisdom is, perhaps, a similar kind of mistake. The perfect system of the dabbawallahs thus stands for the dispensation of the gods or the fates in the film, who have a natural place in every truly romantic story and who may, likewise, be supposed to be right even when they are wrong.

Saajan, an insurance adjuster, is also famous in his company for never making a mistake, though he too relies on old-fashioned methods to make his calculations — and on the reading glasses that he carefully replaces in their case during lunch. These he must extract again and replace on his nose to read the notes that Ila begins sending him when she realizes that her lunches have gone astray. Yet Saajan claims to have made not one but many mistakes in order to save the job of poor Shaikh, who has in fact made them, and also forged his university credentials. Saajan relies on his other reputation, for misanthropy, to persuade the boss that he is not doing what he really is doing by covering for Shaikh. Another thread of connection comes with Ila’s story in one of her notes to Saajan of how her brother committed suicide after failing his university exams. Now, she has learned that her husband is having an affair and also has to confront a life-changing failure. Does she take her brother’s way out or Shaikh’s?

Saajan’s own sense of failure is less dramatic, but it allows him to enter into the feelings of the other two. He is merely lonely without his wife but uninterested in other people until Shaikh and Ila in their different ways break through his defenses. Even when they do, he feels that his life has arrived at a dead end. Briefly, on learning of her husband’s affair, he contemplates arranging a meeting with this mysterious woman and perhaps eloping with her, as she has proclaimed her intention of taking her small daughter, Yashvi (Yashvi Puneet Nagar), and running away to Bhutan. There one Indian rupee is reputed to be worth five rupees in the local currency. Also, says Ila, in Bhutan she has heard that they don’t have Gross Domestic Product — that which both her husband and Saajan labor so seemingly endlessly to produce — but Gross Domestic Happiness.

But on the morning of their proposed meeting, Saajan goes back into the bathroom of his house to get something he has forgotten and notices that it smells the way he remembers his grandfather’s bathroom did when he was a boy. Then, on the train to the office, a younger man says, “Uncle, would you like to sit?” He is now, he realizes, officially, an old man, though he doesn’t know exactly when he became one. Too old, at any rate, for a young woman like Ila — whose own feelings of failure, in another nice bit of thematic symmetry, also arrive through the nose as she smells the strange woman’s scent on her husbands shirts in the laundry. In the midst of all these goings-on, Ila’s father dies after a long illness during which he was virtually helpless. Her mother (Lillete Dubey) finally feels free to confess how tired and disgusted she is by her years as a wife-caregiver. For her, widowhood is a relief.

The would-be romance between Saajan and Ila that every movie convention points us toward is therefore given a remarkably realistic context — that of loneliness, infidelity, domestic drudgery and even religious difference, as Saajan is meant to be Christian while Ila is Hindu. Shaikh, a Muslim, asks Saajan to come to his wedding in lieu of the family he hasn’t got and so confirms the emerging paternal relationship he has somehow developed with the older man. This, in turn, suggests that the age and religious differences, at least, between Ila and Saajan might not be too great to be overcome, but the ending is left slightly ambiguous, though upbeat. It’s a lovely film marked by fine performances, especially by the two principal actors, and conforms to its director’s reputed watchword: less is more. It’s a lesson of which Hollywood is badly in need, if unlikely to learn from.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.