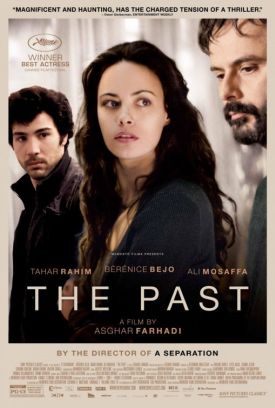

Past, The (Le Passé)

The critic for Variety called The Past (Le Passé) by Asghar Farhadi (A Separation) “an exquisitely sculpted family melodrama in which the end of a marriage is merely the beginning of something else.” Insofar as this is not simply a banality — since everything that ends is the beginning of something else — it is the opposite of the truth. The end of the marriage between Marie-Anne (Bérénice Bejo) and her Iranian husband Ahmad (Ali Mosaffa) is not “merely” anything, not even the end of the marriage, and nor does it mark the beginning, as Marie herself would wish it to do, of her new life with Samir (Tahar Rahim), the man with whom she is expecting a child and trying to build a life together. The past will not release its hold on Marie, nor on Samir, nor on their respective children from previous relationships — nor on Ahmad whose presence in Paris for the formality of his divorce from her is not legally required but requested by Marie, thus giving rise to the question of how far either of them can hope to be free of the past they once shared with each other.

But the principal way in which the past is present in the movie appears to us in the form of Samir’s comatose wife, Céline (Aleksandra Klebanska) — whom we don’t see until the final frames but who then makes an impact magnified by the looming presence of her absence hitherto. Céline had suffered from depression for some time before trying and failing to kill herself, thus ending up (as we suppose) among the living dead. Gradually, it emerges that answering the question of the proximate cause of her attempted suicide will be the key to understanding what kind of hold the past continues to have on everyone else — and how unrelenting that hold is likely to be. That moral entanglement comes only gradually into view, however, as this master story-teller takes his time to sketch in the relationships between Ahmad and Marie, between Marie and Samir, between Samir and Lucie (Pauline Burlet), Marie’s teenage daughter, and Lucie’s with both Marie and Céline before the latter’s suicide attempt.

At the same time as we learn about all these relationships we also come to see that the film’s principal character is in many ways Samir’s six- or seven-year-old son Fouad (Elyes Aguis), whose relationship to all the others is the means by which they reveal the most about themselves. His sufferings on account of the illness of his mother and the uneasiness about it felt by all the adults around him, as well as by his father’s attempts to integrate him into a new family while she continues to lie permanently unconscious in the hospital, are heart-breaking in their poignancy. The only one of the major characters who is completely innocent in the moral morass behind and around them, poor little Fouad is also the only one who has to learn to apologize — even as he confirms what all the others more or less openly admit, that apologies are useless as charms against the ills we suffer as a result of our past actions, let alone those of other people.

Samir is jealous of Ahmad, thinking there is still unfinished business between him and Marie. Why did she not book a hotel for him? Why are they fighting just as if they are still together? In his view, something remains obviously unresolved. Lucie professes to hate Samir and to love Ahmad, which also creates jealousy. But Lucie harbors a secret. First she tells Ahmad that Céline committed suicide by drinking detergent because of Samir’s affair with her mother. When Ahmad reports this back to Marie and she reports it to Samir, Samir is indignant and swears he can produce an employee of his (he runs a dry-cleaning business) who will vouch for the true version of events: namely, that Céline, in a depressed state, had a violent altercation with a customer which resulted in a further entanglement with the employee, Naïma (Sabrina Ouazani), an illegal immigrant. The latter had tried to get away when Céline called the police. As a result, Samir had asked his wife to leave, while showing solicitude to Naïma, and Céline had not been speaking to him for days.

All this appears to be true, but there are further revelations to come, suggesting ineradicable guilt for everyone but little Fouad and inescapable pasts for everyone, including Fouad, for whom nothing but further heartbreak seems to lie ahead. It is an appallingly bleak vision of the lives of these flawed but always sympathetic characters, and yet it doesn’t come across as being quite so depressing as it sounds. Maybe it’s just because of the pleasure we get out of the unraveling of the mystery, something rare enough in our experience of American movies in recent years, but learning the truth does have its consolations, which we may feel on behalf of the characters who learn it as we do. A true and non-caricatured portrayal of the bad allows room for the good, a portion of which must be allotted to all these sinners — if only on account of their capacity to feel guilt and remorse. These are things that they, at least, unlike the despairing Céline, still have to fall back on. That’s got to make it worthwhile to carry on, both for us and for them.

@

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.