Monumental Disasters

From The American SpectatorIn explaining why he wants to save, as he sees it, the cultural heritage of Europe, stolen and spirited away into Germany by the retreating Nazis, George Clooney’s character in The Monuments Men (which he also directs) says: “If you destroy their achievements, their history, it’s like they never existed.” I don’t quite buy this. Even leaving aside the fact that the Nazi art-lovers (in emulation of the Führer) were not destroying it but squirreling the art away in salt mines against the hopeful day of Germany’s revival — the scene in the movie where they are shown burning some paintings including Raphael’s lost “Portrait of a Young Man” is fictional — the “they” in this case is too numerous and must include far too many whose achievements, let alone their history, were never in any danger of being destroyed. At least not by the Nazis.

Moreover, the natural casualties of time have destroyed the achievements of most ancient civilizations, apart from a few famous ones (and even a lot of theirs), but it’s not at all “like” they never existed as a result. We may wish we knew more about the existence of, say, the Hittites, especially if the knowledge were in the form of artifacts or writings created by themselves, but we still know something about them, including the fact that they existed. It would be more accurate to say that, to the extent that a culture’s art is eliminated, we are cut off from the richest and most satisfying form of knowledge about it. I risk belaboring the point for the sake of the curious irony that Mr Clooney’s reverent apostrophe to art comes in the midst of a work of art — schlock art, it’s true, but still art — which is busily falsifying history as only Hollywood knows how to do it.

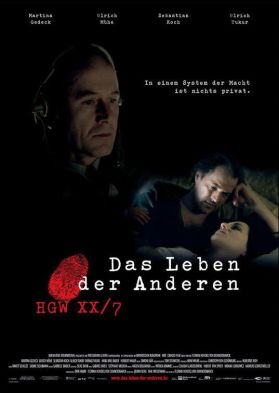

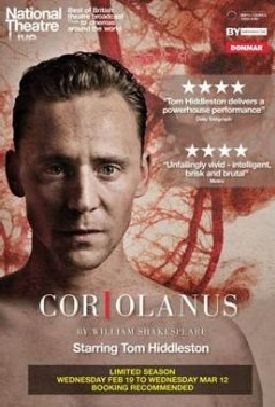

This is not surprising. Nearly 70 years after the Nazis were comprehensively defeated, we seem to be intent on cutting ourselves off from our own history. Now it would be truer to say that the generation of the real-life Monuments Men and the mental (as opposed to the material) world they lived in is in the process of becoming for us, only two generations later, as if they never were — swa heo no waere, in the words of an anonymous Old English poet about the ruined remains of Roman Britain. Like the poet, we may regard the works of the past as the product of giants, but we no longer know what they were for. I have written before, for example, about the mirth occasioned in the audience at the Shakespeare Theatre in Washington by Racine’s tragedy of Phaedra (see “An American Tragedy” in The American Spectator of November, 2009). Lately, at the STC’s Harman Hall there was an HD TV transmission of the much-praised Josie Rourke production of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus from the Donmar Warehouse in London which also caused nothing but amusement in the audience the night I attended.

|

To be fair, the production itself hardly seemed to know that the play was a tragedy. Since its hero was a military man who gloried in the slaughter of his country’s enemies, I suppose it would have been unreasonable to expect much in the way of audience sympathy for him. On the plus side, in addition to the jollity occasioned by his being cowed by his mother and his subsequent downfall, we could enjoy the spectacle of our hostess for the evening, Emma Freud, great grand-daughter of Sigmund, and Ms Rourke giggling together over someone’s description of the play’s star, Tom Hiddleston, as “the sexiest man in the world.” And there’s another remarkable bit of irony, since the tragedy of Coriolanus is precisely his refusal to make the transition, so gracefully managed by Mr Hiddleston himself, from hero to celebrity.

The one thing we demand from our celebrities is also the one thing demanded by the Roman mob and fatally refused by Coriolanus, namely to condescend to them by pretending to be just like them and certainly no better than they are. There is an argument to be made that celebrity culture has rendered tragedy itself impossible, but it has certainly made the tragedy of Coriolanus impossible. Why put it on, then? Well, partly for the sake of sexy Tom, at least to judge by the heavily female audience — many of whom must have come to the Donmar from the Noel Coward Theatre a couple of hundred yards away where sexy Jude Law was playing Henry V. But also for the same reason that George Clooney, another distaff dreamboat, thought it a crowd-pleasing move to preach about “art” while wearing the uniform of an American army lieutenant, circa 1944.

Both the uniform and the love of art, that is, are obvious bits of posturing, but they’re the kind of posturing that audiences love, flattering their own self-conceit as patriots — at least insofar as they are anti-Nazi — and art-lovers, even if they don’t want to know too much about the art they supposedly love. They are also Shakespeare-lovers, just so long as Shakespeare is suitably updated and made safe for them by the likes of Josie Rourke. In other words, audiences today have no patience for the pity and terror of Aristotelian tragedy. They want to be flattered, not frightened, by self-identification with the larger-than-life figures on screen of whom the celebrity culture has taught them to regard themselves as equals. Whether this process can be considered art at all as Shakespeare and Raphael were once considered to be art is a question for another day. But there can be no doubt that it cuts us off from our cultural heritage by causing us to lose the knack of seeing it as it was seen by the people who created it.

This is the cultural complement of a more general historical project of patronizing the past which we can see at work in the explosion of outrage that greeted comments by the British education minister, Michael Gove, at the beginning of the year to the effect that we might try making an effort to see the famously horrible First World War, the centenary of whose outbreak occurs this year, as people at the time did: that is, in terms of “patriotism, honor and courage” and not “a misbegotten shambles — a series of catastrophic mistakes perpetrated by an out-of-touch elite.” Good luck with that, Michael! The misbegotten shambles is by now far too deeply ingrained in our culture.

He had in mind, among other examples, Joan Littlewood’s musical farce of 1963, Oh! What a Lovely War, whose revival this year at the Theatre Royal Stratford East, one of a whole triumphalist panoply of anti-war dramas on the British stage commemorating the anniversary year, answered by representing Mr Gove himself as a donkey — perhaps as an allusion to General Ludendorff’s apocryphal description of the British army in that war as “lions led by donkeys.” Elsewhere, an historian of no less stature than Niall Ferguson answered Mr Gove’s characterization of the war as just and necessary by calling Britain’s participation in it “the biggest error in modern history.” Naturally, the hidebound establishment of cultural revolutionaries in Britain welcomed what they regarded as the conversion of a conservative historian to their cause.

|

Meanwhile in Russia, where they take their history more seriously, a whole cable network was shut down for suggesting that maybe Leningrad should have surrendered to the Germans rather than enduring the 900-day siege that cost the city so dearly during World War II. This was not merely another bit of tyranny on the part of Vladimir Putin, though doubtless it was that too. He is far from being alone in Russia in hanging on to the old fashioned, patriotic view of World War II. You only have to compare the new film of Stalingrad by one of his admirers, Fyodor Bondarchuk, with the miserably feeble Monuments Men. Though way better than the latter, the former suffers from the technique of 3D IMAX, which it is supposedly the first non-American movie to use, and from a too-intimate scale for would-be epic. But what Western critics more typically object to (I write before its opening in the US) are its “stereotypes.”

As is often the case, this critical pejorative can be taken as code for the movie’s traditionalist, patriotic approach to that war, admittedly an easier one to feel patriotic about today than World War I. Anything that portrays people as behaving in ways once represented as appropriate to their sex, nation, profession or social position is now critically verboten — as if it were illegitimate in itself to look at the past as the people who lived in it did. Not only, it seems, are we unable to react to a story of heroism on the heroic plane, we are not allowed to do so. A critical sensibility which celebrates artificiality and fantasy in the comic-book movies that have become Hollywood’s stock-in-trade has thus made the illusion of real and not super-heroism the one bit of illusion and artificiality we will no longer tolerate. Who knows? We might even end up thinking World War I was justified.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.