Noah

If there is anything that is clear about the occasionally unclear Judeo-Christian Scriptural account of the Creation, it is that it was an act of anthropocentrism. Mankind was seen by the author or authors of Genesis as the masterwork of God, who is said to have created man in his own image and to have given him dominion over the rest of the creation. All the rest of the Bible, in both Testaments, has to do with God’s relationship with men, not animals or any other part of the Creation. Accordingly, if there is any doctrine or belief about or representation of the Biblical account which we can be sure is false to it and to its spirit, it is the fashionable view among the literary hangers-on of the environmentalist movement that mankind is a disease of nature or a bit of filth from which the properly natural world needs to be purified. “The world has cancer, and the cancer is man,” as the Club of Rome’s Mankind at the Turning-Point puts it.

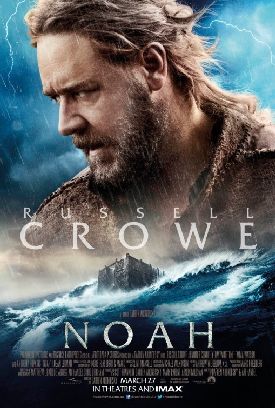

That is not a possible point of view for anyone claiming to be “true to the essence, values, and integrity” of the Biblical story of Noah, as Darren Aronofsky and the other makers of Noah do. Yet their Noah (played by Russell Crowe) would be right at home among the Club of Rome types. In short, he is a nut job. J. Hoberman, who thinks the movie “the most Jewish biblical blockbuster ever made,” says that it “presents the spectacle of a literal-minded patriarch run amok.” But to be literal-minded you need a literal text, a piece of writing, to be literal-minded about. Neither the Biblical nor the movie Noah has any such thing. The God of the Old Testament speaks directly to Noah and is all business about what the latter is to do and the exact dimensions of the Ark he is to build. The movie Noah gets his instructions from “the Creator” (as he is always referred to there) in dreams or agonized and picturesque meditations, just like the radical environmentalists of today whom he so much resembles. We don’t know exactly what these instructions are, but they apparently include what he believes to be an order to murder his own new-born grand-daughters.

As A.O. Scott of The New York Times delicately puts it, “Noah’s instability — he walks up to the boundary that separates faith from fanaticism, and then leaps across it — is not, strictly speaking, in the source material.” Likewise, violence, corruption and wickedness among men are all mentioned in the Genesis account as being among God’s reasons for destroying all life on earth, bar Noah and family and the animals on his Ark. But the men in the movie are treated as belonging to a different breed from the gentle, vegetarian Noah and his diminishing kind. He is said to be descended from Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, while those he calls “men” — his enemies as well as God’s — are in the line of descent from Cain, who killed his brother Abel, and have proceeded in Cain’s murderous spirit to build an “industrial civilization” which has, as we surmise, despoiled the planet, turning the primeval Garden into the desert landscape we see here. “Wickedness” in Noah, therefore, is not the sort of bad behavior which has been known as “sin” for thousands of years but rather the sort of environmental destruction that has only taken sin’s place among the faction of “intellectuals” who, in the last fifty years or so, have gradually taken over as custodians of the Western moral and religious traditions.

It should hardly be necessary to point out that the Bible is a part of that tradition and demands to be seen in its context, not treated as a mere quarry for the materials out of which a new tradition and a new morality are to be constructed. There are some good things about Mr Aronofsky’s Noah. I particularly liked his setting up the bad guy — it’s a movie, so of course there has to be a bad guy — called Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone) as a sort of proto-Nietzschean warlord confronting a man of faith. “A man isn’t ruled by the heavens,” says Tubal-cain; “a man is ruled by his will.” And yet, like Nietzsche, Tubal-cain appears to be angry at God for not existing. “I am a man, made in your image,” he cries out to the heavens. “Why will you not converse with me?” It almost approaches plausible exegesis to see mankind’s rebellion against God in terms of jealousy of the man with whom God, apparently, does converse. But the moment is lost amidst the movie’s awfully movie-ish trappings, most notably the computer-generated rock-creatures called Watchers, said to be “fallen angels” who defied the Creator by trying to help mankind and who are supposed to be the Biblical “giants in the earth” of antediluvian days.

But these glowing-eyed, six-armed cartoon monsters are no more obviously anachronistic than Noah’s environmentalist pieties. Those who object to seeing the Scriptures subjected to such violence are often accused of defending a literalistic interpretation of them, but the opposite is the case. Mr Aronofsky can get away with what he does because he can claim to hew to the story’s literal telling, so far as it goes, only filling in “gaps” from other sources or his own imagination. The reason literalism is inadequate for understanding the Bible is that it leaves out context, which is also what Noah, the movie, does. Or, rather, it invents a wholly new context, recognizable as coming from Hollywood’s fantasy-factory, teamed up with fashionable environmentalism, which is clearly out of place when inserted into what purports to be a Biblical story. Without the context which gives the Bible its meaning — at least to those for whom it has meaning — the story of Noah is radically diminished, reduced to a trendy political parable. If even some Christians and Jews profess to regard the movie as harmless, or a plausible reading of Genesis, it must be because trendy political parables are now taken for granted as all that movies are capable of.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.