Some Eminent Utopians

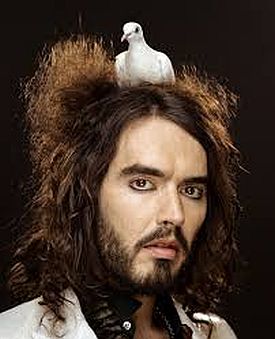

From The New CriterionFirst, an update to my dispatch of six months ago (see “The Truth Will Set You Free” in The New Criterion of December, 2013). Then, you may remember, I discussed the celebrated confrontation on British television between the man I and many others have called the Grand Inquisitor of the BBC, Jeremy Paxman, and the actor, celebrity, comedian and all-round Renaissance Man, Mr Russell Brand, who made known on that occasion his commitment to revolutionary politics while refusing utterly to commit to any alternative to the system he sought to destroy. For some reason, this coup de theatre was widely seen as a great victory by the anti-establishment darling over one of the established media’s most respected figures. Since then, Mr Paxman has announced his retirement, and it has been suggested that that decision, in spite of the BBC’s wish for him to stay on through next year’s general election, may have something to do with the Brand interview and another with a certain Dizzee Rascal, whose views on the issues of the day may not have seemed worth his inquisition.

As it happens, Mr Brand has not been standing still either, and his name was again linked to that of Mr Rascal (as Mr Paxman insisted on addressing him), né Dylan Mills, when their works, including Mr Brand’s ghost-written My Booky Wook and Mr Rascal’s Paxman interview were proposed for inclusion on a new English syllabus for the principal qualifying examination for university entrance. The OCR examinations board — O stands for Oxford, C for Cambridge and R for Royal Society of Arts — is the successor organization to the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES), for whom I used to dabble in the examining trade when it was still a respectable one many years ago. Under criticism, it appealed to “diversity” as its justification for placing these pop cultural celebs in the company of Shakespeare and Jane Austen. But the move was widely seen as the education establishment’s thumb in the eye to the Conservative Education Minister, Michael Gove (about whom I wrote in February), who had promised that the new version of the A-level examinations would be more rigorous. They’ll give him rigorous!

|

Similar announcements in recent years of the further penetration of popular culture into the formerly staid world of education are a periodic media recreation in Britain. The last time around I seem to remember was when the lyrics of Amy Winehouse and Bob Dylan popped up on an exam paper at Cambridge — something which I imagine is now too routine to be reported. On this side of the Atlantic, as Mr Brand and Mr Rascal were making their waves in Britain, a young “data scientist” named Matt Daniels was announcing the results of a new study — “data”-driven, naturally — comparing Shakespeare and Melville to a selection of popular rappers and hip-hop artistes. “Literary elites love to rep Shakespeare’s vocabulary,” wrote Mr Daniels, a rap lover, so he decided to compare it to that of various popular hoppers. Traditionalists and culture-lovers will be happy to learn that the Bard finished above the median for linguistic ingenuity and Melville well above it, though neither was anywhere near so impressive in his use of “unique words” (in a sampling of 35,000) as Aesop Rock, formerly Ian Bavitz, whose superiority must presumably be evident in any side-by-side comparison of one of Shakespeare’s well-worn anthology pieces to, say, the second verse of “Leisureforce” on Mr Rock’s 2012 album Skelethon, which begins with a Shakespearean allusion:

Final answer “not to be”, “not to be” is right!

Next question — to build winged shoes or autophagy

Silk screen band tees, take apart a VCR

Ringer off, canned peas, cabin fever mi amor

Patently adhering to the chandelier of key-in-door

To usher in the understated anarchy of leisureforce

Led a purple tongue and ratty caballeros

Up over the black rainbow into the house of mirrors

To become a thousand zeroes, echoing a twisted alchemy

Freak flags, fluttering to circadian free jazz

Sleep apnea, scratching, “bring that beat back”

I doze off, clothes on, nose in the feedbag

Shhh.. Om-nom-nom, blinds drawn

Compost thrown to the spine pile, bygones

Mangy, intimately spaced pylons

On a plot of inhospitable terrain, “Hi mom!”

Shakespeare must be kicking himself that he never thought of Om-nom-nom. Does that count as one or three “unique words,” I wonder? But then Shakespeare would no doubt be the first to admit that you can’t argue with success — for that, too, can be reduced to a mathematical certainty, merely by counting up the numbers of albums sold.

To a certain kind of data-obsessed mind, including all of those I read who reported on Mr Daniels’s interesting findings, not to mention Mr Daniels himself, Shakespeare is like everything else in the world in being identical with those things about him which can be counted. There is nothing else, at any rate, which they find interesting. Therefore, it must go without saying that Shakespeare and Aesop Rock are competitors in the same business, in which the latter produces a presumptively if unexpectedly superior product. Except that, for them, it’s not unexpected, since the computer model — worthless from the point of view of any traditional form of literary analysis — must have been designed precisely in order to produce some such result as this. It’s what the “data” merchants styling themselves as scientists or serious scholars are themselves in the business of, since they can rely on the media to report their sensational findings without inquiring too closely as to whether they demonstrate what they purport to demonstrate. In Matt Daniels’s case, he doesn’t even bother to make an explicit claim that Aesop Rock is superior to Shakespeare. That might make the absurdity of the comparison a bit too obvious. He lets the data speak for themselves.

It’s a familiar trick of the cultural left, which is always in search of what President Obama has referred to in connection with the doctrine of global-warming (also known as “climate change” and, more recently, “climate disruption”) as “settled science.” Maybe it’s because they see themselves and their ideologies as displacing religion at the center of our communal life and, having no first-hand experience of faith, vainly imagine that it can only exist by excluding doubt. Religious believers could have told them that faith and doubt are not antithetical but bosom companions in every believer’s heart. Science, too, could never have existed, let alone made its way in the world, without doubt. But the true believers of the progressive left, terrified as they are of the doubt that threatens, as they see it, their very identity as their country’s and the world’s Illuminati, and who base their claim to power on their ability to cast their light into the remaining dark places of the earth, fasten their death-grip on Science’s throat, demanding of it a salvific certainty that it can never give.

By “science,” you understand, I mean not just the hard sciences of chemistry and physics, mathematics and biology, nor even those plus the so-called social sciences, but any useful process of ratiocination involving anything that can pass for “data” or “evidence” and proving the no longer doubted truth of what their ideology has already taught them. The media are increasingly dominated by such certainty seekers, either debunking old truths or triumphantly confirming the new ones which the Enlightened, of course, knew all along. The latest example is that of the French economist Thomas Piketty, the English translation of whose book Le Capital au XXIe siècle has been greeted with sensational notices by the likes of Paul Krugman, who (you will not be surprised to learn) already knew as well as M. Piketty — as well as anybody — that the super-rich were a menace but had only been waiting for him to come along with the data to prove it. No one supposes that Professor Krugman’s huzzahs need to be qualified by a disclaimer to the effect that M. Piketty has produced a thesis which he, Professor Krugman, was already thoroughly disposed to believe and had, indeed, put forward in nearly identical terms himself but without, presumably, the thoroughness of evidential backing.

Professor Krugman writes that “what’s really new about Capital is the way it demolishes that most cherished of conservative myths, the insistence that we’re living in a meritocracy in which great wealth is earned and deserved.” This observation casts an interesting light on his further and repeated contention that “the right seems unable to mount any kind of substantive counterattack to Mr. Piketty’s thesis.” For the Piketty thesis, at least as Paul Krugman sees it, is like other forms of left-wing economics, including Marx’s — to which M. Piketty alludes in his title, though he disclaims the title of Marxist — in being set up precisely so as to be proof against refutation. It is, as Karl Popper pointed out long ago, not falsifiable, which is what distinguishes it from real science. The “conservative myth” the professor refers to, though it may actually be believed by some conservatives, would be to most as it is to him self-evidently untrue when stated as an absolute, and the “myth” can be exploded by labors far less Stakhanovite than M. Piketty’s. But to Professor Krugman, all you have to do is deny the left-wing premiss that wealth is generally unearned and undeserved (“You didn’t build that,” as our President would say) to become a true-believing meritocrat, ripe for squashing when shown that there is lots of the stuff, as of course there always is, that hasn’t been earned and is therefore, presumably, undeserved.

It’s an intellectual con trick comparable to that of the Occupy movement, which now sees itself as having been posthumously vindicated by the Piketty volume, when it claimed that “capitalism isn’t working.” But capitalism was never designed to “work.” If anything, the opposite. It was the name given by the left to economic reality, so often disappointing to those who dream of perfection, for the sake of the contrast with socialism, which was designed to “work” — and, somehow, never did. That failure could be covered up, however, by the unspoken pretense that capitalism, like socialism and its various welfarist and statist offspring, must also have been created by economic projectors in order to produce utopian perfection and therefore had manifestly failed at the task. The real foundation of Marxist and, indeed, all left-wing politics is the belief — though it’s more accurate to call it an assumption — that, where there are poor people (and where are there not?), it is because other people are rich. The truth of this assumption is what Thomas Piketty is being celebrated — if not, yet, made super-rich himself — for proving.

Except that he hasn’t proved it. His data, it’s true, powerfully suggested that, for the last fifty years or so at any rate, the rich have been getting richer relative to the unrich, but the assumption that the riches of the former have come at the expense of the latter remains just that, an assumption. M. Piketty’s proposed solution to his proposed problem is a worldwide tax on wealth and a marginal rate of 80 per cent on incomes over $500,000 — in other words, world government, something which he himself admits is a utopian fantasy. Yet whenever anything like such a level of taxation has been tried at the national level — as it was in his native France by its socialist president, François Hollande, only a couple of years ago — the relative impoverishment of the rich has resulted in no corresponding enrichissement of anybody else. You might almost think that the unjust excess enjoyed by the rich would not exist if they were not there to enjoy it. And driving them and other ambitious and entrepreneurial folk away, as even The New York Times admits M. Hollande has done, seems to result in hard times for the non-rich as well, though we have Paul Krugman’s word for it that the idea of the rich as “job creators” is just part of “the conservative myth.”

Capital in the 21st Century is riddled with assumptions which are not recognized as assumptions because they are shared by those who have been welcoming it as the vindication of their own assumptions. It assumes not only that looking at questions of the general welfare in terms of wealth and poverty, and at wealth and poverty in terms of the bare mathematical inequality between the two, are the most helpful or desirable way of looking at them, but also that inequality data in itself must imply a political program to remedy such inequality. The scientific certainty with which the book’s ironclad data is promulgated thus imparts itself, in the progressive imagination, to the proposed political solution as well. In this we may compare it to the “science” of global warming, wherein the numbers that are supposed to demonstrate inexorable temperature rise are also supposed inexorably to demonstrate the political necessity of reducing carbon emissions. That economic disaster would result from both these supposed political necessities may not be an accidental consideration for those who believe them to be necessities.

For just as there has been almost no consideration outside the right wing media of adaptation to a changing climate as a better response than a costly and likely failing attempt at reversing the change, so neither M. Piketty nor his most fervent admirers has considered — if we grant for the sake of argument that (as they claim) inequality of wealth is a problem or a threat to democracy — an alternative to taxing it at confiscatory rates for the benefit, primarily, of an ostensibly redistributionist state. One such alternative, proposed by Christopher DeMuth in The Wall Street Journal, is broadening the ownership of capital by putting individual retirement accounts in place of Social Security. But of course, if once the possibility of a non-apocalyptic solution to such problems were admitted, it might also have to be admitted that the problems themselves are less than apocalyptic, which might, in turn, have a truly apocalyptic effect on the political energy and urgency so treasured by the left, who have been (again, in emulation of religion) predicting apocalypse of one kind or another ever since Marx’s day.

In the end, you’d have to say that Thomas Piketty’s utopian dream represents an advance on that of Russell Brand, who seems to have had no idea at all what his would look like, apart from its not looking like the world as we know it. Moreover, the Frenchman at least has the grace and the clear-sightedness to admit that his dream is utopian, though it’s hard to see how his political outlook is not functionally equivalent to Russell Brand’s deeply unserious one, namely that the economic order of the world not only can be but should be destroyed by those who have nothing real to replace it with. But Messrs. Brand and Piketty — not to mention Mr Rascal, who told Jeremy Paxman that “Hip hop is what encourage the youth to get involved in making things better” — benefit from the larger culture’s lately established principle that utopianism is respectable and (therefore) reality is optional.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.