Scandal, or lack thereof

From The New CriterionRob Richards

For just a moment I allowed myself to think that it could be the first sign of a turnaround in the media culture of the past 40 years, or that, by one of those mysterious shifts in the température d’âme that happen from time to time, there might now be a new tolerance, honor and reason and at least a partial abandonment of the scandal craze which has held our public life in thrall for nearly half a century. Of course that would be too much to hope, but I could scarcely believe my eyes at the main headline above the fold in the Sunday Washington Post — the paper which, during Watergate and Vietnam, had itself done so much to create the addiction to scandal which has characterized the American media down to the present day. It read: “Defined by 38 Seconds,” and was followed by the subhead: “Marine sniper in video scandal is remembered as greater than the clip that stalked him.”

True, the on-line version of the story moved the scandal back up front in the headline: “For Marine who urinated on dead Taliban, a hero’s burial at Arlington,” but the piece was full of compassion for the formerly scandalous one, Marine Sergeant Rob Richards, who was broken to corporal and discharged from the service as a result of the scandal.

Almost everything about war is complicated, messy or morally fraught; in this case even more so. A Marine vilified by his country’s leaders and court-martialed for “bringing discredit to the armed forces” would soon be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, the country’s most hallowed ground. On this mid-February night before the funeral, dozens who knew Richards beyond those 38 seconds gathered to celebrate his life.

The implied question — was it fair to judge this man’s life on the basis of a 38 second video? — was never answered in the article, but the implication was that it was not fair. In any case, the question had been raised.

This may have had to do with the immense popularity of Clint Eastwood’s movie of the Chris Kyle story, American Sniper, or the murder trial and conviction of Kyle’s killer in Texas at about the same time. Or maybe, because Richards’s was a do-it-yourself scandal in which the incriminating video had been made by the men involved, the media couldn’t take a proprietary interest in it and so had less of a stake than usual in pursuing it beyond the grave. Most likely, however, Richards himself had engineered his own transition from villain to victim by dying of an overdose of pain killers, said to be accidental. One story always guaranteed to get in the paper is to do with veterans’ suicides, now said to be running at 22 a day. That, at least, is the number given in an article in the Post two years ago, though the paper’s own “Fact Checker” column reamed out Sarah Palin with Three Pinocchios when she repeated a similar claim with the mistaken implication that it applied particularly to veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. But then to the Post as to other media grandees, Mrs Palin commits scandal merely by existing.

And even if Rob Richards’s death was accidental, it seems plausible that the same reason he urinated on a Taliban corpse was reason enough for him to have killed himself, if he had killed himself.

There was a relentlessness to their war. But, on some days, there was also a joy to it. After shooting a Taliban fighter, Richards and [Sgt. Edward] Deptola would often slap hands. Sometimes Richards would do a little celebration dance. “To the average guy, you’d look like a complete psychopath,” Deptola said. Over there, he said, “It made perfect sense.” The down time between missions — recuperating and waiting for another assignment — was often the hardest part. “We’d be like crack addicts,” Deptola recalled. “We were on that adrenaline drug. We’d get our high when we killed people, and the only way to get our high was to kill. We were honestly addicted to killing people.” The more Taliban they killed, the more praise they received from the top brass. The commandant of the Marine Corps set aside a morning to have breakfast with them and laud them for their work. Richards’s commanders recognized his battlefield valor by nominating him for a Bronze Star.

By this point in the article, it was clear that it was not, after all, a retreat from scandal culture on the part of the Post but yet another drearily predictable reproach to the politicans and generals who had sent these poor kill-addicts through the brutalizing processes of war in the first place and who, having taught them to delight in slaughter, then had the nerve to be surprised and censorious when they came back as psychos. The scandal was as great as ever and, in fact, even greater, since the privilege of victimhood had been used to transfer the guilt to those with the power to send men to war.

The implication of the claim that Richards was “a Marine vilified by his country’s leaders and court-martialed for ‘bringing discredit to the armed forces’,” was that it was hypocritical of the country’s leaders to have treated him in this way, since it was their own prosecution of the war that caused the poor man to do such a thing. So familiar by now is this media “narrative” that when “Jihadi John,” the YouTube celebrity beheader of the Islamic State was unmasked as a computer science graduate from London named Mohammed Emwazi, the Islamic pressure group CAGE, run by an ex-Guantanamo detainee, were quick to announce that he had been “radicalized” only after being harassed by British security services. They knew that, by the rules of scandalology, scandal committed by enlisted men or junior officers is routinely used to discredit someone higher up who must have made them do it — even, as in this case, by trying to prevent them from doing it.

|

But the media’s posthumous exoneration of Rob Richards, such as it was, could also be taken as suggestive of a subtle change in the scandal culture which has in recent years tended to alter its focus from crime tout court — or anything that can plausibly be represented as crime — and has concentrated instead on thought crime. For example, you only had to turn to the op ed page on the same day that The Washington Post ran its regretful farewell to the late Mr Richards to find Dana Milbank incandescent with outrage at some scandalously unthinkable thoughts, in which — claimed Mr Milbank and others of the media’s most vociferous Democratic partisans — was implicated the Governor of Wisconsin and hopeful Republican presidential candidate, Scott Walker.

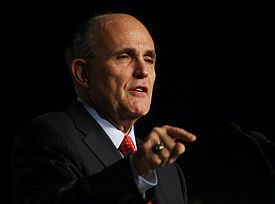

The thought in question hadn’t actually been thought, let alone uttered, by Governor Walker himself but by Rudy Giuliani at a dinner at which the Governor had been present. The former mayor of New York had claimed on this occasion to doubt that President Obama loved his country. Mr Walker had neither agreed nor disagreed with Mr Giuliani, but his silence, thought Mr Milbank, had been a sin of omission so serious that it “ought to disqualify him as a serious presidential contender.” Anyone familiar with Mr Milbank’s partisan sympathies would suspect that, for him, Governor Walker’s real fault lay in having been so successful as the Republican governor of a Democratic-leaning state as to appear a greater threat to the Democrats’ hold on the executive branch than any of his fellow GOP candidates. Some scandal, even one as pathetic as this, was urgently required.

Mr Milbank’s efforts to drum one up were then seconded by a couple of Post reporters who proceeded to ask Mr Walker if he believed the President was a Christian. Scandalously, he answered that he had no information on that subject, had not spoken to the President about it and was, therefore, not going to render an opinion. Mr Milbank got another column out of that, in which he took the Governor’s agnosticism as a dog-whistle to “the far-right fringe” that believes the President to be a secret Muslim — referencing the “furor” already allegedly caused by his silence in the face of Mr Giuliani’s impugning of his patriotism. Though Mr Milbank had no trouble reading between the lines of Gov. Walker’s non-committal response to find the scandalous thoughts he assumed it masked, he called Mr Giuliani “stupid” for finding in the balance of the President’s public statements about America and its enemies a lurking dislike for the country that had elected him on a promise of change.

True, the allegation of such a dislike sounded improbable, but it was not as if it was based on nothing, as Fred Siegel pointed out on the website of City Journal. In any case, it was not so self-evidently untrue as to put Governor Walker under the kind of obligation Mr Milbank thought he was under to contradict him publicly. Both he and the Post’s editorialist charged Governor Walker with cowardice for not rebuking the former mayor. Others then weighed in with a charge of self-pity for his rebuke of the media for neglecting matters of substance in favor of “gotcha” questions like those about the President’s religious beliefs on which he had very reasonably pronounced himself unqualified to comment. None of it served its intended purpose of discrediting Mr Walker. If anything his standing in the polls went up as a result. But it was a reminder to nostalgists like myself of that dim and distant day long ago when there was still something like honor in politics and thus certain things that it was considered at the least very bad democratic manners for politicians to say about each other — including, as it happens, allegations of cowardice — or about their country.

It might even have been a similar attack of nostalgia on Mr Giuliani’s part for a time when no President would have dreamed of criticizing his own country in front of foreigners, as Mr Obama has developed a habit of doing, which led him to make his ill-considered remark in the first place. He said as much in a column he wrote for The Wall Street Journal in which he disavowed any intention of divining the secrets of Mr Obama’s mind or heart.

Irrespective of what a president may think or feel, his inability or disinclination to emphasize what is right with America can hamstring our success as a nation. This is particularly true when a president is seen, as President Obama is, as criticizing his country more than other presidents have done, regardless of their political affiliation.

Not that that got him off the hook with the pro-Obama media, which swiftly went to work to find the further scandal they knew must be there in his attempts to explain and so render un-scandalous the earlier scandal. The Post’s Stakhanovite “Fact Checker,” Glenn Kessler, seized upon his telling an interviewer for Fox News that, although he accepted that Mr Obama was a patriot, “I don’t hear from him what I heard from Harry Truman, what I heard from Bill Clinton, what I heard from Jimmy Carter, which is these wonderful words about what a great country we are, what an exceptional country we are.” It was then the work of a moment to collect instances of the President’s having said things of precisely the tendency that Mr Giuliani claimed he didn’t hear and so awarding Hizzonor a maximum four “Pinocchios” for factual inaccuracy.

I wonder, by the way, if the cutesy “Pinocchio” designation, complete with a cartoon graphic of Collodi’s wooden boy with the unnaturally prolonged nose, couldn’t itself be considered an implied act of semi-deference to the long outmoded honorable principle that one gentleman did not accuse another of lying — at least not, to go even further back in our history, unless he was prepared to stake his life on it. The less robust and, er, couragous practice of awarding Pinocchios may also be taken as a tacit recognition that neither lying by politicians nor the accusation of lying against them is to be considered as anything like so big a deal anymore as it once was.

Glenn Kessler professed to understand that, Pinocchio or no Pinocchio, he could hardly have been said to have discredited Mr Giuliani’s “opinion about the tenor of the President’s remarks.” (Emphasis added.) He might, indeed have gone further and mentioned the obvious possibility that avowals of a love of country might actually be more necessary for a politician who didn’t love it than for one who did. Or that there were occasions when the President’s professed love of his country were only there to accompany his criticisms of it and thus to create a sense of balance. That was perhaps his act of semi-deference to the old “water’s edge” principle in restraint of criticism that the mayor was accusing him of violating — not, indeed, by the literal import of his remarks but by their tenor.

|

Such distant echoes of the old honor culture are everywhere when you know where to look for them. They are, I would say, present in the idea of scandal itself, at least as it used to be understood. As it happened, coincidentally with the would-be scandals of Governor Walker and Mayor Giuliani, the Post ran the first of two stories that, had they been about anybody but Hillary Clinton, must surely have disqualified him or her as “a serious presidential contender.” As the headline to the second of these stories put it: “Foreign governments gave millions to foundation while Clinton was at State Dept.” That would be the The Bill, Hillary & Chelsea Clinton Foundation, now said to have assets of some $2 billion. And yet there was hardly a mention of this on the Post’s editorial or op ed pages.

More promising for scandal connoisseurs was the news a few days later of Mrs Clinton’s having, while Secretary of State, improperly used a private e-mail account rather than the government one required by her Department’s own regulations. There were some stern words uttered by the usually sympathetic media. “The public deserves answers, not stonewalling, from Hillary Clinton,” thundered the Post. “Saturday Night Live” even did a skit about it, though its mockery was directed rather at her ambition, her stiffness, her wonkishness, her sense of entitlement and her cavalier attitude to critics than any suggestion of actual wrong-doing. The reaction among the media at large was typified by the more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger attitude of Chris Cillizza of the Post who wrote that “it reminds and reinforces for people many of the traits that they do not like in the Clintons” — such as that “they don’t think the rules apply to them.” It also reminds and reinforces for people the extent to which the rules don’t apply to them, and Mrs Clinton has been tacitly deemed to share in the immunization against further scandal her husband has enjoyed since the homeopathic dose of impeachment, now nearly two decades ago. But I wonder if, in the intervening period, big media’s having come out as openly loyal to the Democratic party doesn’t rather suggest that scandal can no longer apply to anyone but Republicans. Too bad there is no echo from the past to tell them that scandal must cease to be scandal when it can be discounted as no more than a further esclation of partisan rhetoric.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.