Cuddlers and cutthroats

From The New CriterionThe Ed-stone

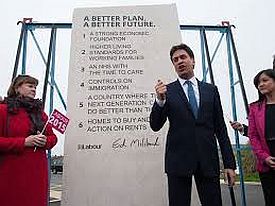

In the campaigning for the British general election in May, the prize for most bizarre stunt would have to go to the limestone slab which the leader of the Labour party, Ed Miliband, had engraved with six vague promises taken from the Labour manifesto and signed by himself and which he promised to have installed in the garden of 10 Downing Street so that he could see it through the window from his putatively prime ministerial desk. Alas, at least partly on account of the ridiculousness of this attempt to impersonate Moses the law-giver, he never got to occupy that desk or view the admonishment of the stone tablet, dubbed “the Ed-stone,” whose post-election fate remains unclear — though various jokers have pretended to sell it on eBay for derisory sums. Yet the attempt to have Labour’s agenda literally set in stone suggests that, at some level, Mr Miliband must have been dimly aware of the problem with the Labour campaign which eventually sunk it, namely that people didn’t trust him or his party. Or they trusted him even less than they trusted his victorious rival, David Cameron.

Equally revealing, perhaps, was the public demonstration of feeling that was the runner up to the tablet of stone in the stunt stakes. This came at the end of a curious television “debate” in which, as the two leaders of the governing coalition, Mr Cameron and Nick Clegg, had declined to participate, Mr Miliband, faced off against Nigel Farage, representing the anti-immigration, anti-EU party UKIP, and the female spokespersons for the Scottish and Welsh nationalists and the Green Party. At the conclusion of the evening, the three women came together in the middle of the stage for a group hug while Mr Farage and Mr Miliband were left to look on with bemusement. In the next morning’s Daily Telegraph the headline to an article by Claire Cohen celebrated what it called “The leaders’ debate hug that showed Britain wants a new cuddlier politics.”

|

Those with long memories might have wanted to ask, “Cuddlier than what?” Weren’t there endless jokes made about the “bromance” between Messrs Cameron and Clegg five years ago when they brought their two parties together to form the Coalition? Yes, and just look how that turned out! As Steven Swinford wrote in the Telegraph “The Tories were remorseless in the way they attacked their former Coalition partners. Having worked closely alongside them for five years, they went for the jugular during the election campaign. Of the 23 seats they targeted to win the election, 22 were held by Liberal Democrats, many by former government colleagues.” As Rupert Darwall wrote, Mr Cameron’s “path to a majority was by shoving the proverbial hose pipe down the throat of his drowning coalition partner.”

On the other side, at the height of the campaign Danny Alexander, the Liberal Democrat who served in the coalition as chief secretary to the Treasury, purported to reveal a “secret Tory plan” for £8 billion in welfare cuts, including “slashing child benefits and child tax credits.” It didn’t turn out to be quite the bombshell he had hoped, and Mr Alexander lost his own seat in Scotland to the party of Nicola Sturgeon, one of the huggers.

The veiled menace behind much of her party’s campaign in Scotland, both this year and last during the referendum on independence, also gave the lie to any idea of her cuddliness. Yet it is undoubtedly true that the media, in America as in Britain, love to tell us that we want cuddlier politics — or, to put it in the American way, bipartisanship. Whether or not people actually do want this is another matter. Though the desire for compromise and comity is a socially acceptable one to express to a pollster, in the voting booth people have long been opting for the kind of divided government which has made these things impossible. We know but may not want to believe that politics has always been and presumably always will be less a matter of ideas or debates than it has of the orderly management of the hatred between social factions — hatred which is usually seeking temporary cuddles with those who hate the same people.

Ms Sturgeon made that plain enough when she appealed to the other huggers and Mr Miliband to join with her and the Scot Nats in excluding the hated Tories from power. At another television debate, Ruth Davidson, the Scottish Tory leader asked Ms Sturgeon what was it about Mr Miliband that she believed made him a suitable ally for the SNP. “He’s no’ a Tory,” she replied. As Alan Cochrane of the Telegraph, paraphrasing Ms Davidson’s views put it, “The way she says it, ‘Tory’ is not a person or a belief but, rather, something that you’d scrape off the sole of your shoe.” Though there is no reason to doubt that that is the way Ms Sturgeon really feels about Tories, she must also be canny enough to give expression to such feelings only because she knows they resonate with large segments of the electorate, especially in Scotland where Tories have been almost an extinct species since the days of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership.

She also knows that her party owes its very existence to the Scots’ having only very lately ended their long love-affair with Labour. It therefore must have seemed sensible, even if it took a certain chutzpah on her part, to have invited Mr Miliband, after his and his party’s mugging in Scotland, to join in the hugging. And, although he had before him the example of the existing coalition to remind him that it is in the nature of things for the cuddles not to last, he seemed for far too long to entertain the idea of going into coalition with his fellowTory-haters from north of the border and only ruled it out definitively when it became clear that the prospect of a minority Labour government’s being dictated terms by Ms Sturgeon’s charmless Caledonian militants was scaring English voters into the Tory camp.

Meanwhile, Mr Miliband was seeking an alliance of convenience of his own by putting on his Frog-he-would-a-wooing-go best to pay a call on Russell Brand, the hippie comedian (see “The Truth Will Set You Free” in The New Criterion of December, 2013) whose ten-million followers on Twitter were widely supposed, at least in the media, to make him a power-broker among the young. Mr Brand is most famous for having advised his young followers not to vote, preferring as he does (or claims to do) a revolutionary solution to the country’s problems. But the honey-tongued Mr Miliband must have persuaded him that his own and thus Labour’s sharp turn to the left had sufficiently differentiated them from the hated Tories that, even if he had not made the Revolution redundant, he had at least offered the proto-revolutionaries a chance “to take decisive action to end the danger [sic] of the Conservative party.” Like Ms Sturgeon in Scotland, he clearly understood the bad odor in which the Tory brand stood, at least among the sort of people who “follow” Mr Brand.

And also in the media, for they are many of the same people. “Russell Brand has endorsed Labour — and the Tories should be worried,” thought Owen Jones of The Guardian — among many others on the left who saw this as some kind of breakthrough for Labour. In fact, like the Sturgeon surge, it may have helped bring about the unexpected Conservative victory, since most of their gains came, by design, at the expense of their more moderate Lib-Dem ex-partners.

These were reduced to a rump of only eight seats as opposed to the 56 they won in 2010 — the same number now held by the Scot Nats, who had only won six in 2010. No one had expected such a good result for the Conservatives, or quite such a disastrous one for the Lib-Dems, and a constant theme of the media’s post-election analysis was searching for an answer to the question: how did the pollsters, all of whom were predicting a virtual dead heat, get it so wrong?

According to the Telegraph, Peter Kellner, president of the polling company YouGov said,

“What seems to have gone wrong is that people have said one thing and they did something else in the ballot box.” He said: “We are not as far out as we were in 1992, not that that is a great commendation.” But he blamed politicians for relying too heavily on polling data during their campaigns and said they should instead concentrate on standing on a platform of what they believe in. He said politicians “should campaign on what they believe, they should not listen to people like me and the figures we produce.”

That might seem as hopelessly naive as Ms Cohen’s call for cuddles, but at least it had the merit of being the only note of true humility sounded among the election’s big losers. As in 1992, when the Tories under John Major also won in spite of polls predicting either a Labour victory or a hung parliament, the popular explanation of why “people have said one thing and they did something else in the ballot box” was what, at the time, Rob Hayward was the first to call the “shy Tory” voter. Asked for his view today, Mr Hayward wrote that the polls “were misled by the soft Labour vote: those voters who were initially tempted by Ed Miliband and then shied away from voting for him in the cold reality of the polling booth.” But the question then arises as to why cold reality is only being recognized as such in retrospect? Mr Hayward merely reiterates that the Tories were shy without explaining why.

One reason must surely be that rumors of people who are lying to pollsters have proved unfounded in the past. I first remember hearing them in 1964, when Goldwater supporters who really believed in the resonant quality of their candidate’s slogan, “In your heart, you know he’s right,” couldn’t believe that such people would not, in the end, vote with their hearts. People must be for him, really, even if they were telling pollsters for social reasons they were against him. They were, of course, wrong. So were those who, I seem to remember, said similar things about George H.W. Bush in 1992, or Bob Dole in 1996 or Mitt Romney in 2012. Could it be that now, in Britain, as in 1992, we are at last seeing the last desperate hope of the electorally unfavored coming true? If so, why there? Why then?

Pollsters in Britain have long been aware that their results tend to skew too much to Labour and to under-represent Tory support. There is a similar, though smaller error in favor of the Democrats in America. They normally correct for that bias in reporting results, but it seems that this time they didn’t correct enough. If that is so, it must be because they failed to take account of the increase in the level and intensity of hostility to conservatives and conservative ideas in the media and the popular culture — an increase that the likes of Nicola Sturgeon and Russell Brand had obviously picked up on. For if the “shy Tories” of 1992 were back, in the intervening 23 years, “shy” has ceased to be what Bertie Wooster would call le mot juste. Now, it seems, “self-loathing” sounds a bit more like it.

As Hugo Rifkind in The Times put it

It’s not just pollsters to whom Tories lie about being Tories. It’s also themselves. For some people, Toryism and their own self-image simply isn’t compatible. “Do you think you could be friends with a Tory?” I’ve heard people ask each other, all my life. “Actually friends, though? Would you kiss one? Euuugh! I mean, you certainly couldn’t introduce one to your mates . . .” Then they’ll go out on polling day, these very same people, and what will they do? That’s right. They’ll vote Tory. Just like they’ll send their kids to the private schools whose alumni they claim to despise, and pay to avoid the NHS they claim to cherish. And they won’t even feel, quite, that they are being hypocrites. “It’s not what I am,” they’ll say to themselves. “It’s just what, right now, I have to do.”

Mr Rifkind’s column was written tongue-in-cheek, but he may well be onto something. There must be others in the same boat as the friend of another columnist for the Telegraph who told her on election day: “I can’t believe I’m a Tory — I hate myself.” If there are enough such self-hating Tories to have made the difference in the election, the implications both for polling and for electioneering in the future are tremendous. Already before the election, the failure of the polls to budge in either direction during the month-long campaign caused some to wonder if there had been any result from all that effort and all that money spent to reach the hearts and minds of the voters. Afterwards, it may begin to look as if it was all as useless as Ed Miliband’s tablet of stone.

For if it is also a socially acceptable response to the question of how you will vote to dismiss both sides as equally mendacious and irrelevant, it doesn’t mean that this is not in some sense true. The politicians themselves must know that their rhetoric and their promises are heavily discounted in the political market-place — which is why Mr Miliband’s stunt was both undertaken and ridiculed — and yet they feel that they have to make them in order to uphold the fiction of their own importance. As Anthony King has written in Who Governs Britain? “there is something surreal about the way in which British politicians comport themselves at the moment. Few . . . are liars but most of them are living a lie.”

“The untruth,” writes Philip Collins of The Times “is contained in the assumption that the mantle of power is still theirs. To international money, to supra-national politics, to devolved UK governments, to judges in various jurisdictions, to the chatter of social media and the daily rebuke of the opinion poll, power is fractured and diffuse.” It’s true that neither Parliament nor the Prime Minister has the power it once had, but they never had the power that their promises now so often suggest they are arrogating to themselves: the godlike power to make life fair and equitable to the satisfaction of those who have learned to regard it as a personal grievance against the world that it is not so to them.

As it turns out, all parties, just like the major parties in America, feel more or less obliged to pander to Russell Brand and his kind — people who feel themselves to be unfairly treated and who are determined to treasure their grievance about it until they can find someone crazy or unscrupulous enough to promise them redress against the universe, or whatever bit of it they have managed to persuade themselves is oppressing them, whether it’s the English or the “one per cent” or, as in the case of apologists for the rioters of Baltimore, just “the system” as allegedly designed by white people for their own benefit. Even the aggrieved do not really believe that politicians have this power, which is why there are so many of them affecting, like Mr Brand, an all-encompassing cynicism about politics. Come the revolution, things will be different. They, too, are partners in upholding the central falsehood on which politics is now based, as much in America as in Britain. For if they didn’t have that residual, childlike faith in someone’s ability to give them the happiness of which they feel unjustly deprived, they would have no faith at all and must give way to despair.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.