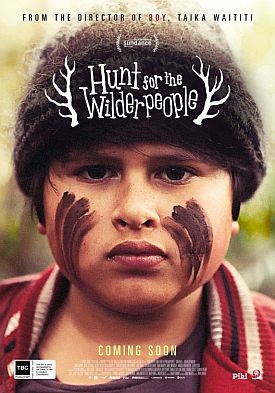

Hunt for the Wilderpeople

In Hunt for the Wilderpeople by Taika Waititi, director of Boy, Ricky Baker (Julian Dennison) is what used to be described as a juvenile delinquent — a term which has now gone out of fashion, I suppose, because it labels people and implies a fixed identity, even though the “juvenile” part would once have implied that it was only a developmental and not a permanent delinquency. But nowadays juvenility is no longer limited to the young, which may be why Mr Waititi has to extend his casting reach all the way to 69-year-old Sam Neill to find an adult who is adult enough to take Ricky in hand and at least start the process of turning him into a man. Even then, he is only able to do so through a tragedy and then a series of accidents that sends the two of them, Ricky and Mr Neill’s Hec, on the run from the police through the New Zealand bush.

Based on the novel, Wild Pork and Watercress by the New Zealander Barry Crump (1935-1996), Hunt for the Wilderpeople is like Boy in showing how the young “process” (to use a word Ricky himself seems to have picked up from the government-therapeutic complex) the popular culture that always surrounds them, no matter the class or social background, even when they carry it with them into remote places where otherwise it might not be found. But the point is only occasionally to illustrate what happens when certain moral and social realities collide with a popular culture designed for and based on fantasy.

For, also as in Boy, it is not always clear that Mr Waititi appreciates the seriousness that lies behind the comedy of this collision. The villain of the piece is child welfare lady Paula (Rachel House), mindlessly reciting her own personal mantra, “No child left behind,” when it is obvious she cares nothing for the children but only for the petty bureaucratic power she is able to exercise over them and others, ostensibly on the children’s behalf. Paula does a comic double act with a policeman called Andy (Oscar Kightley) of whom she speaks scornfully to his face, averring he is not a “real” policeman, meaning not like the ones who carry guns. It soon becomes clear that she rather fancies carrying a gun herself.

But making her, along with some other unsavory characters and a lot of unspeaking police and military men dressed in the scary anonymity of uniforms and body armor, the only visible representatives of the official culture suggests that the author is himself not entirely un-Ricky-like in his willingness to romanticize the “gangsta” culture that Ricky accepts at face value and aspires to emulate when he names his dog “Tupac” or finds himself and Hec on a “Wanted” poster like something out of the Wild West. “We’re famous!” he says excitedly, and he looks forward to a shoot-out with the police — “like Scarface.”

His own mantra, the counterpart of Paula’s absurd “no child left behind,” is “I didn’t choose the skuxx life, the skuxx life chose me.” This appears to be a double irony. Ricky apparently thinks “skuxx” means “gangsta” cool, but to the gangsta it means (according to the Urban Dictionary), a poseur who affects the dress and jive talk and hip hop style without being properly of it. As if the gangsta look and style were not itself the ultimate affectation. Anyway, it makes for an ironic commentary on Paula’s description of Ricky as “a very bad egg.” He’s clearly not so bad as either of them thinks.

Still, I wish that Mr Waititi did not feel the need (presumably for political reasons) to pretend that he’s not bad at all, or that the language and imagery of fashionable outlawry has done him and millions like him any favors. Hec also retains his street-cred by previous run-ins with the law, but he could have acted as more of a corrective to Ricky’s childish fancies than the movie allows him to be. As it is, he talks briefly to Ricky about “the knack,” which he describes as “a way of figuring things out without thinking too much about it — or, more important, talking about it.” But a little more talking (not to mention thinking) would have been helpful both to him and to the audience in trying to figure out this delightful little film.

@

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.