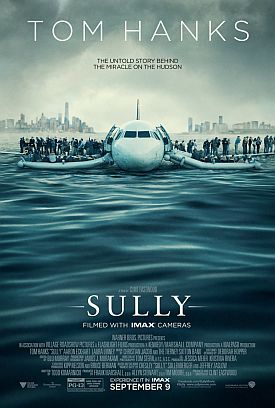

Sully

Whatever else it does or doesn’t do, Clint Eastwood’s Sully makes an interesting case study for those of us who think a lot about the relationship between movies, or popular culture in general, and real life. Because the whole story of “the Miracle on the Hudson” on January 15, 2009 took only seconds to unfold, and because it was caused by Canada geese being sucked into a jet airliner’s engines and was therefore seemingly uncomplicated by any human drama behind the scenes, it must have been obvious to Mr Eastwood from the start that some such drama had to be confected for the movie — if not quite ex nihilo then by way of exaggeration of what really happened.

He chose an inquiry by the National Transportation Safety Board which actually took place months after the plane’s “forced water landing” — as Captain Sullenberger (Tom Hanks) insists on calling it, as opposed to a “crash” — relocating the hearing to the days immediately after the event and showing his hero, still suffering from post-traumatic stress (we can watch his CGI nightmare of crashing the plane into Manhattan), being badgered by his bureaucratic inquisitors for taking an unnecessary risk with his passengers’ lives by ditching in the Hudson instead of making an emergency landing at one of the New York area airports. A computer simulation is said to have found he could have made such a landing. Sully, then, in the time-honored fashion of courtroom drama, gets to explain to his dunderheaded tormentors why the simulation is wrong.

It never happened in real life, but the story sort of fits with a familiar movie “narrative” of corrupt bureaucrats working against ordinary guys and gals who have behaved heroically and on behalf of corporate interests, in this case the airline (U.S. Airways, as it then was) and its unnamed insurers, who are supposed to be trying dishonestly to prove the hero no hero at all. There is also, slightly buried here, a man-vs-machine drama — the computer simulation versus Captain Sully’s having “eyeballed it” — as well as just a hint of man-vs-media as, for a brief moment at least, the TV reporters who are such a big part of the story scent scandal arising out of the NTSB inquiry.

The more interesting machine in this case, I would have thought, was the Airbus A320, which took the water landing like a champ and didn’t break up or sink on the spot, giving all the passengers and crew a chance to be rescued, but I guess Clint didn’t want to let a European-based multinational corporation take any of the credit away from brave Captain Sully and his equally brave co-pilot, Jeff Skiles (Aaron Eckhart). Man-vs-media would have been more congenial to my own prejudices, but that theme remains undeveloped and is, in any case, as much a misdirection as the others. So are hints, never followed up, of trouble at home between the Captain and his wife (Laura Linney), who has little to do and is only present at the other end of several anguished cell phone calls.

In an email to The New York Times, Captain Sullenberger himself, now retired, justified Mr Eastwood’s misrepresentation of the NTSB’s proceedings by writing “that the tension in the film accurately reflected his state of mind at the time. ‘For those who are the focus of the investigation, the intensity of it is immense,’ he said, adding that the process was ‘inherently adversarial, with professional reputations absolutely in the balance’.” In other words, he felt like he was being treated by the investigative panel like a hostile witness if not a culprit, even if he wasn’t, and that his career, reputation and pension were, therefore, all at stake. Against that, you have to put the words of the actual chairman of the inquiry, Robert Benzon: “Sully is worried about his reputation, but this movie isn’t helping mine.”

His name and those of the other panel members have been changed in the movie, but he feels understandably aggrieved anyway. Too bad. Nobody’s going to remember him, but everybody’s going to remember Sully. Good old Sully. If the price his legend demands to live on in Mr Eastwood’s film is Robert Benzon’s own exiguous reputation, who besides Robert Benzon and his family is going to mind? It’s not like he’s going to become a supervillain, the Joker to Sully’s Batman. He’s just a faceless — and pseudonymous — bureaucrat, no more than a cipher standing in for the blind, heartless Washington establishment that everyone hates anyway. Except that, maybe, such falsifications of history are why people hate it in the first place.

I don’t know. You can see the arguments on both sides. But I find that the movie does leave a bit of a bad taste in the mouth, in spite of such greatly moving scenes as that in which Captain Sully refuses to leave the Hudson ferry boat that has picked him up until he has had a head-count of passengers and, finally, someone comes up to him with nothing more than the baldly stated number: 155. It is the number of the passengers and crew on board US Airways flight 1549. And then the number is repeated. As one of the rescuers says to a panicked passenger, “Nobody dies today.” It would no doubt be foolish to expect anyone in Hollywood to feel bad about setting the genuine emotion of these moments in the midst of so much fakery, but I can’t help feeling kind of bad about it myself.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.