No honor among thieves

If the only tool you have is a hammer, they say, everything looks like a nail. Cognizant of this not-so-old saying, I have tried to limit the occasions for dragging into these columns my particular hobby-horse, which is the demise of the old honor culture, both in America and in the West generally. But sometimes that absence, that gaping hole in our more general culture which distinguishes it from all others, cries out for notice. Now, during the cultural revolution of the last six or seven years, is one of those times, for it is through this honor-shaped hole in our culture that the left is driving all the social and political energies that are just now reshaping that culture and all its institutions.

Allow me to explain. The omnipresent ideology of the left is inherently totalitarian. When you define yourself and your political praxis by the inerrancy and inevitability of your beliefs — as those do who routinely proclaim themselves to be “on the right side of history” — you can, of course, brook no dissent from them. How can anyone dissent from History itself, except by denying its undeniable truths? Mark Hemingway of the Federalist calls attention to a remark of Barack Obama’s from 2013: “We’re going to try to do everything we can to create a permission structure for them [i.e. congressional Republicans] to be able to do what’s going to be best for the country.” Mr Hemingway explicates:

“Permission structure” is a phrase that’s been used by marketing executives for many years, and was apparently in common usage at the Obama White House. The idea is “based on an understanding that radically changing a deeply held belief and/or entrenched behavior will often challenge a person’s self-identity and perhaps even leave them feeling humiliated about being wrong. … Permission Structures serve as scaffolding for someone to embrace change that they might otherwise reject.”

In other words, so confident was President Obama — and, presumably, those of his fellow Democrats who think as he does — of the truth of their ideology that they believe those who disagree with it must secretly or unconsciously know the truth themselves but require a “permission structure” to acknowledge that truth without feeling humiliated. It can be only the prospect of such a humiliation that prevents them from admitting their error.

For the ideologue, therefore, there can be no such thing as agreeing to disagree, that fundamental building block of liberal democracy. Nor can he adopt a spirit of compromise, except for temporary tactical advantage, or accommodate different points of view. These, too, have no place in the totalitarian’s world-view. Disagreement with any part of the ideological project amounts to a rejection of the whole and must, therefore, when the totalitarian ideologue comes to power, be criminalized or otherwise purged from public life by censorship or cancellation. That is what old-fashioned, non-ideological liberals so often fail to understand when they see their former comrades turn to belief in the regnant, neo-Marxist ideology and, simultaneously, turn against what once seemed to be the bedrock liberal belief in free speech.

These are some thoughts to ponder after the indictment of President Trump by the fanatical Fani Willis, the ideologically driven district attorney of Atlanta-Fulton County — under a racketeering statute, forsooth — for expressing his opinion that the election of 2020, which he lost to the current incumbent, was “stolen” from him. This opinion is treated, by the terms of Ms Willis’s indictment, as a “lie,” even though it is patently not a lie. Leaving aside for the moment the question of the mens rea, or guilty mind, which should be a requirement of anything designated a “lie” (as opposed to a mere mistake), you can call something a lie only when you know the truth that contradicts it. If you don’t know that truth — and the people who insist they know the 2020 election was not stolen cannot possibly know that — then to call the contradiction of it a lie is itself a lie.

That the election is officially not “stolen” is a simple fact, and it was that official act, of proclaiming the election valid, that Mr Trump was trying to stop because he thought that official truth at variance with the actual truth. When he failed to stop it, he had to accept the official truth and vacate the office of president on January 20, which he did. But he, or anybody, was and still is at liberty to think the official truth an error, even a deliberate one, because the actual truth, as opposed to the official one, can never be known. This is because there can never be an audit of an election with so many mailed-in ballots. That Democratic legislators and judges in battleground states arranged in advance for this impossibility of auditing the election is suspicious on its face, and a reasonable person might regard it as a justification for Mr Trump’s belief that the election was stolen, or “rigged,” as it might be more accurate to say.

In any case, it’s absurd to say that he knew it wasn’t stolen — nobody knew that — and lied about it in order to steal the election himself, which is what the Georgia prosecution alleges. Among other things. For along with Mr Trump, 18 of his lawyers or advisers were indicted at the same time by Ms Willis, essentially for agreeing with his wrong opinion, in order to give color to her charge of conspiracy. The ideological logic is impeccable. If the denial of a truth which is, ex hypothesi, undeniable is a criminal act, so is supporting or advising or defending him who denies it. All are equally guilty for defending themselves and their wrong opinions when the Truth is known — presumably even to the defendants themselves.

Amusingly, however, there are some indications that the legal jihad against the former president is actually helping his campaign to regain the presidency. “Trump is seizing control of the narrative as much as he possibly can,” writes an outraged Arwa Mahdawi of the Guardian’s “Week in Patriarchy” column, “and attempting to turn his mugshot into a badge of honour rather than disgrace.” How dare he not accept the humiliation we in the media have, by “seizing control of the narrative” ourselves, attempted to heap upon him — as much as we possibly can! “Trump’s Trials Don’t Interrupt His Campaign” writes Michael Tomasky of The New Republic — “They Are His Campaign.” And whose fault is that, if not those who have forced the trials to take place in an election year? Cet animal est très méchant, as the old French song puts it. Quand on l’attaque il se défend. The beastly Mr Trump, likewise, is very wicked indeed, and so are his lawyers and advisors — for defending themselves when they are attacked.

“He’s been booked. His mug shot has been taken. And incredibly this might not end Donald Trump’s race for the White House,” writes Julian Zelizer for CNN. Even more incredibly, it may put him back in the White House! Do you suppose that could have anything to do with the nature of the charges against him?

How we cling to the idea that those we hate must be humiliated when we expose, as we imagine we do, their manifold wickednesses to the world. “Vladimir Putin’s humiliation is far from over,” wrote Svitlana Morenets for the London Daily Telegraph after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin in August. Have I missed something? Has anybody seen any evidence of this “humiliation” of the Russian leader? I’m afraid it’s only in the wishful imagination of Ms Morenets. “Bumbling Biden’s response to the Hawaii wildfires has shamed America” wrote Madeline Fry Schultz for the same paper.

Shamed America? It didn’t even shame him or, so far as I can tell, any of his supporters — unless you count as evidence of the media’s secret shame their suppression, for the most part, of the President’s remarks, during a brief Hawaiian drop-in, comparing the deaths by fire of hundreds of Hawaiians, not to mention thousands more who have lost everything, to a kitchen fire in his home by which he might have lost his wife, his Corvette and his cat — not necessarily in that order.

Shame, like its opposite, honor, depends on a shared set of values. Not all values, but just a few of the kind which were once thought to transcend mere social, racial, religious or national differences, let alone political ones — values like honesty, loyalty, courage, patriotism, sexual continence, respect for others who are different from oneself, or who hold contrary opinions, and a willingness on the part of the strong to help the weak, or those who are being bullied or persecuted. The possession of these qualities used to be honorable to the possessor, their absence shameful. In many places it still is. But on the left, perhaps only courage still qualifies as honorable — and not even that, if it is the courage of, say, Confederate soldiers — while all the rest can be often, if not always, positively shameful, especially if they appertain to the politically disfavored.

For so long as the law was widely regarded as being justly and impartially administered, criminality was shameful, while the law-abiding were honorable, and judges and others who upheld the law were addressed as “your honor” or “the honorable.” These titles are now just the meaningless vestige of happier days. The story of the American West in thousands of movies made before about 1960 was told again and again as the emergence of just and impartially administered law, and law enforcement, out of the chaos of merely private grievance, cupidity or revenge. But that kind of law no longer exists — or at least the public perception of it on both left and right no longer exists, which amounts to the same thing, so far as honor is concerned.

In other words, no one today need be ashamed of being exposed as a law breaker — not for so long as there is, as there nearly always is these days, a substantial constituency which regards the law thus broken to be an unjust one, or as having been unjustly administered. Hence the Trump “mugshot” as “a badge of honor.” Surely the left-wing apologists for riot and looting and assaults on the police during the last year of the Trump administration should understand that better than anybody.

That they don’t, or pretend they don’t, is one measure of the depth to which the tribal divisions in our polity have reached. It’s also the measure of the left’s success, over a century of unremitting cultural effort, in discrediting the traditional honor culture which turns out, in retrospect, to have been our only protection against this same cultural descent into tribalism. It is no accident, I believe, that everything became political only after nothing was anymore honorable.

“If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country,” wrote E.M. Forster — an oft-repeated sentiment to which many a mid-20th century bosom seems to have returned an echo. But it turns out that betraying your country, and the disinterested administration of the law for which it stands, is betraying your friends, at least the ones who happen not to be in your little ideological tribe, not to mention the neighbors and fellow-countrymen who used to rely on you for citizenly solidarity in honoring what was once described as the majesty of the law.

The law had first to lose that majesty, by the death of the honor culture, before it could be “weaponized,” as it now is by Attorney General Merrick Garland and his minions in the pursuit of private vendettas — against, for example, non-violent January 6 defendants sentenced to decades in prison — and partisan political interests. Honor’s absence was also implied in last month’s column (see “No Surrender” in The New Criterion of September, 2023) about the political uses of scandal — scandal being the one vestige of the old honor culture that the media still find useful for their purposes, even though the scandals, in the absence of the shared cultural value of honor, always have to be artificially inflated by the media’s black arts (like the Trump scandals), or minimized (like the Biden scandals), according to which tribe is supposed to own them.

Scandal implies shame. But shame, detached from honor, requires a legal buttress to be of any use, as anyone can see from the oft-remarked shamelessness of our political class since at least Bill Clinton’s day. I always thought it a mistake for Republicans to use the law to try artificially to thrust a sense of shame on Mr Clinton and his supporters and apologists — an enterprise which was no more successful then than it is now with Mr Trump and his supporters and apologists. In fact, the apparent fury behind the multiple legal assaults on the latter must owe something to the Democratic memory of the former — just as it owed something to Republican resentment at the “high tech lynching” of Clarence Thomas, recently renewed, seven years earlier.

In all these cases, the instant descent into tribalism, now apparently a permanent feature of our political culture, could have been prevented by a shared sense of honor, and especially the honor due even to an enemy. Now that there is no such thing as an honorable enemy, it is but a small step to regarding, as so many of us now do regard, our putatively honorable colleagues on the other team, or in positions of public trust, as enemies. And when seen as enemies, they commonly behave like enemies.

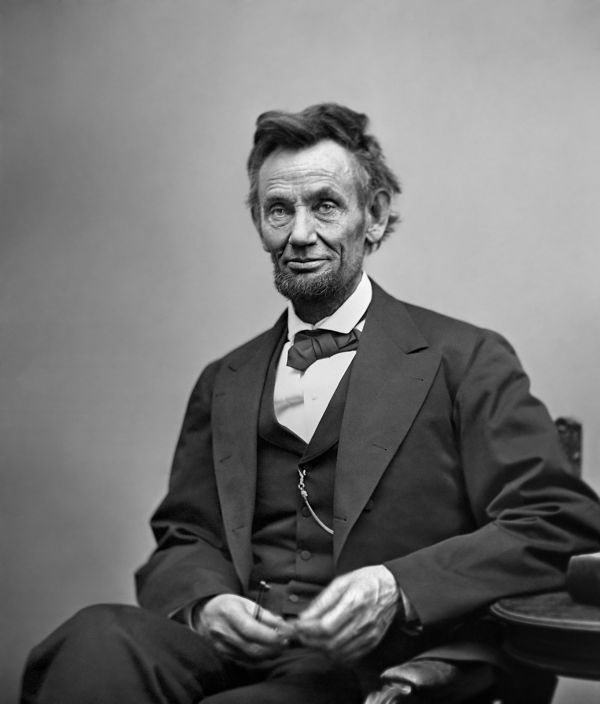

This happened once before in American history — in the early to mid-19th century, as chronicled in Joanne Freeman’s The Field of Blood (2018). Then it took a bloody Civil War to restore some sense of unity in the “sacred honor” for which, according to the Declaration of Independence, the first American Revolution was fought. And even then, it took the magnanimity towards the defeated rebels inspired by Lincoln’s second inaugural address to re-establish, eventually, the sense of national honor whose duration roughly corresponded to the years in which the United States emerged as the premier power in the world. In the time of America’s decline, however, thanks to inherently divisive ideological thinking, I can see no Lincoln on the horizon, prepared to bind up the nation’s wounds.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.