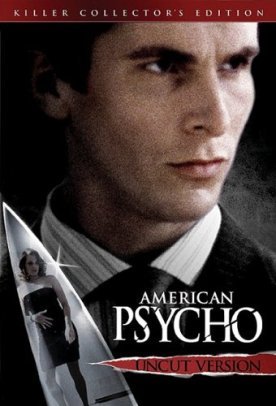

American Psycho

American Psycho is as a movie as it was as a book, not a serious work of art but merely something designed to be talked about in the media and thus to confer money and celebrity upon its now plural authors. This is important, because not all books or movies that are talked about in the media are designed for that purpose. Some novelists, and even some film-makers, I believe, still are motivated by exclusively artistic purposes; more are mainly motivated by their art but have the potential for headlines and feature stories somewhere in the backs of their minds. This is only natural, and we mustn’t be too hard on them. But the ones who write or film solely in order to become media phenoms ought to be pointed out by critics so that people at least know when they are being manipulated.

The novel by Brett Easton Ellis, first published in 1991, was always such a concept. Ellis offered his sensation-seeking audience just enough subtleties and a congenial political subtext (guess what its politics are) in order to persuade them that they were not being sick or perverted by reading this sexually slashing and gorily graphic account of a young Wall Street trader who murders people for sexual thrills. Instead, they were reading a serious commentary on our times. Mary Harron’s cinematic adaptation of the novel provides viewers the same reassurances, though as the film has been cut so as to receive an “R” rating, perhaps they are not all absolutely necessary. But both novel and film are still good examples of how easy it is to create what will be hailed as a work of serious art if only you have the right social and political attitudes.

Here is the scenario. In the late Reagan years, a rich young Master of the Universe type called Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) finds that his soul has been effectively snuffed out by years of devotion to nothing but making and spending money, by having everything he wants. He doesn’t seek to change his life but rather to push it to a logical extreme. He loses all sense of perspective on the world, loves only himself and the image his expensively pampered figure presents to himself in the mirror, cares only to impress colleagues by having fashionable things before they do, or to get into fashionable restaurants, and gets sexual thrills only by murder. He tells us all about himself in his voiceovers, including the rather centrally important fact that he does not exist. Not really. There is, he tells us, “an idea of a Patrick Bateman but no real me….I simply am not there.”

This is at one and the same time a way of his alienating himself from his actions in killing and carving up people and a supposedly deep philosophical statement: here is man utterly drained of humanity by his soulless devotion to money and status-conferring consumer goods. Yet the implication is that this is only a slightly extreme version of what everybody on Wall Street had become in the Reagan years. Bateman gets away with his murders, it turns out, because nobody really knows who he is and nobody really notices when his victims disappear. The people in his circle are more or less interchangeable. Even close friends don’t recognize each other and call each other by the wrong names. When in an uncharacteristic moment of vulnerability and panic Bateman confesses to his lawyer his murder of a colleague, Paul Allen (Jared Leto), whom he had hacked up with an axe and then pretended had flown to London, the lawyer says he knows he’s joking because he’s just had dinner in London with Paul Allen.

Was the murder a hallucination or is it the phantom victim in London? After that murder Bateman made Allen’s apartment—nicer than his, which is why Allen had to die—a charnel house for the women he has killed. Yet when he lets himself in one day he finds the place being renovated, the corpses missing from the closet and a real estate agent quietly suggesting that he leave. The point is that you trade a bond or two and the next thing you know you’re chasing terrified women through your apartment building with a chainsaw. Asked by a woman at a party what he does on the Street, Bateman replies: “Murders and executions mostly” but the noise drowns him out. Naturally the woman assumes he has said “mergers and acquisitions.” But the similarity in sound is meant to suggest a similarity in substance.

This same point is driven home over and over and over again, without rest, without respite, and if you happen to believe, as I do, that people who work in Wall Street are not, after all, noticeably less human than most other people, you are going to find yourself, as I did, getting rather impatient with the film’s hectoring and tendentiousness. This all comes to a head near the end as Bateman and his pals, whom neither he nor we can tell apart, sit watching Ronald Reagan on television talking about the Iran-Contra affair. One of the pals says that Reagan “presents himself as this harmless old codger, but inside…” and then Bateman’s ever-present voiceover butts in and says: “But inside doesn’t matter!” One of the others says, “Come on Bateman, what do you think?” but his only reply is that great contemporary motto of the morally and intellectually indifferent: “Whatever.”

Of course the media and the critics in general just love this stuff because it plugs into their two favorite pastimes: feeling superior to Republicans and feeling miserable and alienated about the state of the nation. It is all a pose, of course, but then Ellis’s book and Ms Harron’s movie are poses too. Everybody knows that everybody is putting it on and only unashamed sensationalists and the stupider sorts of art-consumers will believe that it means anything real, serious or true. But, hey. Whatever.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.