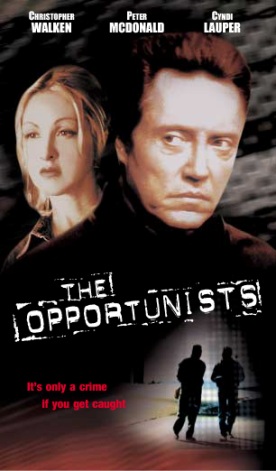

Opportunists, The

The Opportunists by Myles Connell is a pleasant surprise. To some extent, it represents a throwback to the good old days in Hollywood when even the most hard-boiled gangster movies, or movies later taken to have glorified the criminal life, could be relied upon to portray a moral world characterized by inflexible certainty about what constituted right and wrong. To be sure, as befitted a popular form of entertainment, movie morality was of a rough-and-ready, working class sort which had no time for subtleties and refinements. But however sympathetic those old-time directors and writers might have allowed themselves to become towards a particular criminal, it would never have occurred to them to condone crime itself.

That of course has long since ceased to be the case in Tinseltown, and the result is that even when they make a movie with something like the old moral sense about it, it ultimately lacks the power imparted to the old movies by a belief, shared by moviemakers and their audience alike, that (for instance) “crime doesn’t pay.” Even if a movie today shows crime not paying, the criminal failure is bound to look like an accident, rather than the hand of God, or fate, or the inexorable moral order written in the stars that was once so clear, even to Hollywood stars. For a time The Opportunists manages to create something resembling that old criminal nemesis, but it seems almost unreasonable to expect it not to show the gods turning indulgent in the end.

Mind you, given that morality in any philosophically coherent sense is a dead letter in the movies today, this movie offers us the next best thing, which is an act of unexplained unselfishness that bespeaks, at least, an appealing optimism about the mysterious human capacity for moral, or at least honorable behavior. Vic Kelly (Christopher Walken) is an ex-con who is trying to go straight as the proprietor of a small garage in Staten Island and not having much luck at it. “The regular citizen thing isn’t working out so well,” as he ruefully admits. Others are more brutal: he owes money all over town and can’t pay it back. His aged Aunt Dee (Anne Pitoniak) is about to be thrown out of the Catholic nursing home she lives in because Vic’s checks keep bouncing. He is even threatened with eviction from the garage.

His girlfriend, Sally (Cyndi Lauper), owns a bar and offers to lend him the money he needs to get back on his feet from her little renovations fund, but he is too proud to take it, particularly as his troubles have already made him contemptible in the eyes of his neighbors. “Once a f***-up, always a f***-up,” says a cop whose classic Buick Riviera has had an apparently botched repair from Vic. Roughly at the same time two serious temptations to return to a life of crime come into his life at once. A long-lost cousin from Ireland, Mike Kelly (Peter McDonald), turns up with the expectation of serving as an apprentice to his famous safe-cracker of an uncle. At the same time, Pat Duffy (Donal Logue), a security guard for an armored car company, presents him with a can’t-miss plan for an inside job that amounts, as Mike assures him, to “money for free.” Inevitably, Vic falls prey to these temptations.

It is regrettably over the top that our sympathies for Vic and his struggles for petty bourgeois respectability are so unalloyed with any lingering evidence of his criminal past. His entire rap sheet seems to consist of a single bank job,—for which he turned himself in. “My wife, when she found out what I did, took the kid and left,” he tells Mike. “So I had the money but nothing to spend it on. So I gave it back.” He got eight years. Poor robber-man! But at least he is meant to be sympathetic for acknowledging conventional ideas of morality rather than defying them, as a typical Hollywood hero-villain would have done. Thank God that at least the temptation to hipness has been resisted!

Moreover, the suspense and the humor involved in the planning and execution of Vic’s caper are very well managed. More cannot be said without giving away the ending, which has perhaps already been too much hinted at. But I can warn you to watch out for that solitary and unexplained — perhaps unexplainable — honorable act upon which the whole story turns. I don’t say that more could not have been done with it, and with the enigmatic character of the person who performs it, but we should be grateful to have been given as much as we have.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.