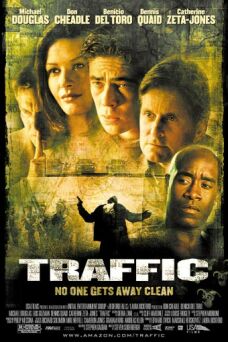

Traffic

Here are the good things about Traffic, Steven Soderbergh’s new and ambitious — and, indeed, epic-scale movie treatment of what is still here and there called the “drug war.” It does not glamorize drug taking, or drug supplying, though about a third of it deals with the first and about two- thirds with the second. Nor does it treat the drug problem in simplistic terms or preach at us about it, either against drugs or against banning them. Its point of view seems to be that drugs are very bad for your health but that prohibition may be even worse for the social and legal health of the country. It takes more or less full account of the reality of market forces which make the interdiction of supply such a hazardous and quixotic enterprise, but it admires the police who risk their lives in that enterprise, even when they are themselves skeptical about its wisdom or efficacy. This is an intelligent and well-balanced approach to the social and political problems posed by drugs.

On the human side of it, one or two of the film’s performances are also very fine, especially that of Benicio del Toro as a Mexican policeman, Javier Rodriguez, who finds that his efforts to bring down a drug cartel are being sponsored by a rival cartel, and Don Cheadle as Montel Gordon, an American undercover cop charged with the protection of a vital witness in the case against a San Diegan drug lord. Montel and his partner, Ray Castro (Luis Guzman), make up one of those cop double-acts, whose main purpose is to provide an excuse for witty one-liners and whose male-bonding — which partly depends on the one-liners — has long been a mainstay of the American cinema. They have their counterpart south of the border in Javier and his partner, Manolo (Jacob Vargas), who are less witty (speaking only Spanish to each other) but equally wedded to the conventions of the cop buddy-flick.

But there are just too many things in the movie that are wrong or silly or hokey or far-fetched. At the top of the list comes the hopelessly pat device of giving the national Drug Czar, a tough judge from Ohio called Robert Wakefield (Michael Douglas), a 16 year-old daughter who is a heroin addict, selling her body on the street for drug money. This is way too obvious as a narrative trick, and the only point that it makes is already too obvious, namely that the theory of outlawing recreational drugs is not the same as the practice, especially when the drug user is in your own family. As if that were not banal enough as an insight into the problem, the story of the dysfunctional Wakefield family — Czar Bob, Czarina Bob-ra (Amy Irving) and young Czarovna Caroline Bob (Erika Christensen) — is given an improbably happy ending.

This comes about in a family therapy session which comes near to undoing completely the film’s complex and sophisticated understanding of drug addiction with therapeutic happy-talk. Moreover, the scene takes place just after daddy has had one of those dramatic, Mr Smith Goes to Washington political moments so common in the movies — Douglas himself had one before in The American President — but so unfortunately rare in real-life Washington in which, in the very act of parroting the party line on drugs at a news conference, he breaks down and reverses the entire tendency of his life to date. “If there is a war on drugs, then many of our family members are the enemy,” he suddenly announces, as if struck with a blinding revelation. “And I don’t know how you wage war on your own family.”

Funny, he knew yesterday. Or at least he knew enough to try. But knowing generally is not his strong suit, apparently. It never occurs to him that Caroline is a dope fiend — though it is not unusual for her to be out all night — until he catches her in the act. Nor does he even know much about the drug trade, which it is his business to know. There’s a wonderful scene of unconscious humor when he jumps into a limousine in Washington and gets on his cell phone to his secretary: “Clear out my schedule for the next three days,” he tells her. “I’m tired of talking to experts who’ve never left the Beltway. . .It’s time to see the front lines.” And several brief scenes follow of his interviewing border guards and DEA agents in the Southwest.

Three whole days and he’s got the conventional wisdom on the run! I think I’d go with the experts who’ve never left the Beltway myself. But then maybe this lame story of the Wakefields is meant somehow to stand for the general lameness of the War on Drugs. If so, the same would have to be said about the film’s other story, concerning a drug king-pin in San Diego whose far-flung operation extends to the highest levels of Mexican authority and is taken over by his beautiful wife (Catherine Zeta-Jones) — hitherto kept in the dark about his business dealings — after he is arrested. Apart from the relatively minor parts (in terms of the organization, not of the movie) played by Mr. Del Toro’s and Mr. Cheadle’s characters, this story is pretty routine too.

For in spite of the lonely and mostly unavailing efforts of Miss Zeta-Jones to show us something new, the thugs and drug dealers are not anything we haven’t seen before. They are all swarthy and ruthless and trigger-happy and corrupt, drug lords and policemen alike, and (of course) the politicians are the most corrupt of all. As several real-life politicians, including Bill Weld, Barbara Boxer, Orrin Hatch and Don Nickles put in cameo appearances, you’ve got to suppose that their hankering for publicity must have overcome any natural aversion they may have had to looking like fools, and confirming the popular stereotype of them as either feckless or corrupt. Or maybe they are fools. As for the drug lords and Mexican law-enforcement officials, they may be really like this, but even if they are the type is familiar enough from the movies for one to be fairly uninterested in seeing very many more examples of it.

As with the moral of the story, the characters seem borrowed from stock and do not make us see anything with fresh eyes. There is just one moment where a striking reality is sighted, where we have the sense of hitting a nerve we didn’t quite know was there. This comes when poor Manolo is on the point of being executed by a drug lord he’d ratted on to the gringos and asks Javier, or one of his executioners, not to tell his girlfriend, that he died like this. “Tell her I died for some something official. . .something worthy.” For just a moment, as death heaves into view on the horizon, the absurd self-indulgence of the drug culture in all its aspects is forgotten and sinks out of sight. What horrific vision is vouchsafed to Manolo, what sudden realization that his life, like his death, is wasted? Whence comes this unexpected shame in one who has never shown much of a capacity for guilt? And why does junkie Caroline, with so much to be ashamed of, apparently not feel it at all?

Yet this moment and all that it suggests about the mind of those who live to get either rich or high on drugs, never strikes us as a permanent insight of the film itself. Reality appears only to be forgotten again, or to be translated into the appalling sentimentality of the conclusion, where Javier’s own profit from the drug trade is taken out in the form of lights on a kids’ baseball field, so that los niños can play night games. Oh, please! This is like the Czar’s dramatic breakdown in front of the nation’s Carrie Nations: pure Hollywood. When you consider how much of the international drug trade must go to end-users in the film industry, you’ve got to wonder if this is the best way of representing the problem.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.