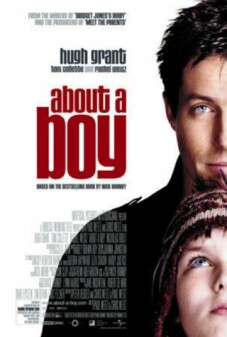

About a Boy

About a Boy is a not-altogether successful adaptation of Nick Hornby’s novel by Chris and Paul Weitz, the team that brought you American Pie and that, therefore, wouldn’t have been many people’s first choice to be entrusted with such superior material as this. For Hornby is that rare figure: a man who is completely in and of the popular culture who nevertheless is capable of looking at it critically, and from an adult point of view. This was evident in Stephen Frears’s splendid adaptation of High Fidelity a couple of years ago, and it is still solidly apparent in this new film, in spite of occasional hints of the self-importance and pretentiousness of American Pie. Under the circumstances, it is remarkable that the brothers Weitz do as well with the subject as they do.

It tells in parallel and with the help of the slightly cumbersome device of twin streams of voiceover narration the stories of a worthless young man called Will (Hugh Grant) who lives only for his pleasures and a deeply unhappy 12-year-old boy called Marcus (Nicholas Hoult) who lives alone with his depressive mother, Fiona (Toni Collette), and is mercilessly bullied at school. The two of them meet when Will decides that pretending to be a single dad and joining a single-parents’ support group (otherwise peopled entirely by women) is a good way to find willing sex partners. On a date with Suzie (Victoria Smurfit) he meets Marcus, who has come along at the behest of Suzie’s friend, Fiona. Will tells Suzie he doesn’t have to work because in 1958 his father wrote a kitschy Christmas song called “Santa’s Super Sleigh,” the royalties from which support his fairly lavishly-maintained bachelor existence in London.

“You mean when carol singers sing it they have to pay you ten percent?” asks Suzie.

“They should, but it’s sometimes hard to catch the little bastards,” says Will, who quickly realizes that his joke hasn’t gone down with Suzie quite as he might have hoped it would. Suzie has not been blessed with much of a sense of humor.

Even if he were able to catch all the carol singers, I wonder if the proceeds of such a song would actually be enough to relieve a man of the necessity of employment. Not for the first or last time, one suspects that Will is a bit of wish fulfilment on the part of Mr Hornby and/or the Weitz brothers. In fact the ruthlessness with which Will insists on his right to be an “island” in spite of the famous contrary assertion of John Donne (which he misattributes to Jon Bon Jovi) is almost beginning to look admirable until the film loses its nerve and swiftly gathers him back into the normal human community, or what passes for it in the hipper postal districts of London. Not that, from a moral point of view, membership in even this sort of normal human community isn’t a far superior aspiration to Will’s happy insularity — he reckons that he’s not only an island, he’s Ibiza — but strictly from the point of view of our enjoyment of the movie, I’m not sure that we would not, by the time we get to the soppy ending, have preferred to stick with Will in his original state.

Will’s attempted seduction of Suzie is hampered by the presence of Marcus — and by Marcus’s accidental killing of a duck in the park, a scrape which quick-witted and plausible Will gets him out of — and is abandoned when they bring Marcus home to find Fiona sprawled unconscious on the sofa, an attempted suicide. When at the hospital the doctor tells Will and Suzie that Fiona will be all right and says that the boy “can go home with you,” assuming they are a couple, Will smiles and says, “My place or yours?” Once again, the joke does not go over well, Will’s tastelessness being brought out and complemented by Suzie’s humorlessness. Unlike his, Mr Hornby’s jokes, and the Weitzes’ jokes based on them, are here and pretty much everywhere else in the film remarkably successful. It is a very funny and enjoyable movie. A laff riot, in fact.

But it also has pretensions to seriousness. At this point, for example, Marcus is given credit for some pretty grown up thinking when he tells us in voiceover that his mother’s attempted suicide has made him realize that one parent is not enough, so he sets out to get his mother married to Will. When it swiftly becomes apparent that this idea is a non-starter, he begins (as one might almost say) to court Will for himself. This is the best part of the picture, since Will, as a sort of spiritually fossilized 12-year-old boy himself, is pretty much just what the hopeless and friendless Marcus needs at this point in his life, while the latter’s rather scary contact with the real world through his mother’s emotional fireworks-show in the end helps Will to grow up — with the help of Will’s first real attachment to a woman, the beautiful Rachel (Rachel Weisz).

It may be taking things just the tiniest bit too far that it is by virtue of his interest in Marcus that Will is able to rise to be worthy of Rachel. Shouldn’t his re-attachment to the mainland be its own reward? But the right note is struck when we see that even someone as selfish as he cannot quite turn away when Marcus comes to him for help when he fears that his mother may be entertaining suicidal thoughts again. Not that he doesn’t try to. “I’m the guy who’s really good at choosing trainers” — that is, sneakers — “or records,” he says. “I can’t help you with real things.” But in the end he can, not only by confronting Fiona but also by saving him from his own “social suicide” at school when he volunteers to sing Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly,” his mother’s favorite song, for her sake at a school concert.

One way to look at the movie is as an essay in “cool.” Will, though he is 38, still sets great store by adhering to what is cool. And it is through his ability to impart some of his own coolness to Marcus that he is able to save him from terminal nerdery, which among British school boys would make him a “wally.” Perhaps the Weitzes also mean to suggest that the suspiciously Hollywoody ending in a happy scene of multiply-blended families is also cool. To my mind, however, that is rather too big a leap. At some level we know that Will has got to stop being cool if he is to start being genuinely human, and that doesn’t happen in this film. Instead, we have the precocious Marcus’s voiceover taking the improbably large and jolly pseudo-family as his new norm, saying “the future’s not in couples. . .”

No, I think maybe the future is in couples, and the children couples beget and raise. And I think that kids are not such wallies as not to know this and to be suspicious of such facile alternatives as the Weitzes have to offer at the end of what is otherwise a most enjoyable picture.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.