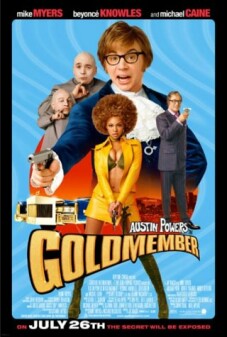

Austin Powers in Goldmember

Formerly, movie-makers and their publicists would ask us critics not to reveal a movie’s ending and so spoil the audience’s enjoyment. Now, in the case of Mike Myers’s Austin Powers in Goldmember (directed by Jay Roach and co-written by Mr Myers and Michael McCullers), they are asking us not to reveal the identities of those making surprise celebrity cameo appearances in the picture for, presumably, the same reason. Even the new love interest of Austin Powers (Mr Myers), Beyoncé Knowles of the pop group Destiny’s Child, is something of a cameo, as this is her first film role, but the ones I can’t reveal make their appearance near the beginning as Austin is seen sitting on a movie set, watching a movie being made of his life with other Hollywood stars playing himself, another love interest, Dr. Evil, Mini-Me and the director of the fictional film.

Of this we see one or two spectacular action-bits, but the real attraction is the comic cameos of the stars who are all, including the director, bigger stars than Mr Myers. The roars of approval from the preview audience that greeted each suggest that the joke is a success. But what exactly is the joke? The Austin Powers series has always depended for its laughs on its audience’s knowledge of pop-culture, and in particular of the conventions of the James Bond movie. This is still the case. But the opening on a movie set seems to signify a much wider range of quotation from other movies than ever before. We swiftly move on from James Bond to Singing in the Rain, Annie, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Godzilla and many more, each of them burlesqued in some way.

The danger in such promiscuity of quotation, as in that of the apparently hilarious cameos, is that the parodic focus on the 1960s and the spy thriller will be lost. Being derivative in this kind of movie is not only not bad, it is of the essence. As with the celebrity cameos, much of the humor is positional — that is, the business on screen is only funny because of who is doing it, and under what circumstances, like having the stiff and very white Dr. Evil doing, or attempting to do, the black body-language associated with a rap number. In such cases, the joke consists of nothing but the quotation, and the laugh which greets it is merely a form of self-congratulation for “getting” it. Nor did the Farrelly-style gross-out jokes appeal to me as much as they doubtless will to the teenage demographic which bulks so large in movie-audiences these days.

Yet in spite of all, we find that the Bond parody has not been exhausted even yet, even at its most post-modern. At least, I still find it funny when the newly-introduced character of Austin’s father, Nigel Powers (Michael Caine), says to one of the armed security guards around Dr Evil (Mr Myers) after judo-chopping two others: “Have you any idea how many anonymous henchmen I’ve killed over the years? And you don’t even have a name tag! Why don’t you just fall down?” And the man obediently does so. But the film’s real achievement is that it also functions as a dialogue with our national memory of the 1960s, a period which the Baby Boomers and to some extent their children love to mythologize, but which, unlike most myths, now looks rather ridiculous.

And looking ridiculous is certainly the point about Austin Powers. One review mentions his hipness but in fact, of course, he is as excruciatingly unhip as those teeth and those glasses and that crude, flag-waving patriotism that is so un-British, never mind unhip. Austin is a hopeless square who thinks he’s hip. He believes that he can be hip simply shedding his sexual and other inhibitions, so he talks about “shagging” and acts sexually liberated while actually looking and behaving at all times like a complete dork. It is what makes him funny, which is what it is very hard to be for the genuinely hip. And, in the course of being ridiculous himself, he points up all the more vividly the ridiculousness of the sixties, now (inevitably) no longer hip.

It is a serious point that those who live by hipness will also die by hipness. Well, semi-serious. I also detect a note of seriousness behind the send-up, continued from the earlier films in the series, of the therapeutic culture. Here, Mr Myers takes the opportunity of Mr. Caine’s appearance to expand on the father-son “issues” that were previously confined to Dr Evil, his mixed up son, Scott Evil (Seth Green) and his clone, Mini-Me (Verne Troyer). This helps to remind us that the gap between the Bond elements and the countercultural elements in the original Powers mix was also the famous “generation gap” of the 1960s. Here, at last, it is bridged. And for the first time, perhaps, we can see that James Bond was the original “Make Love, Not War” guy, since his job was to defuse Cold War crises and so prevent wars in the course of “making love” (as we euphemistically call it) to as many beautiful women as possible.

Thus it seems natural that the scene of general reconciliation at the end — in which, if it is not too giving away too much, Scott Evil (like Malvolio in Twelfth Night) is left out, so as to promise an eventual end to the idyll of love’s triumph — should be accompanied by Burt Bachrach himself performing “What the World Needs Now is Love.” This is in a way the perfect 1960s anthem, more even than the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love” which has an ironic edge to it and lacks the sweet innocence of Mr. Bachrach’s song. The absurdity of this happy ending with its naïve but winsome paean to “love” and the spectacle of evil suddenly turning good with the resolution of the psycho-sexual “issues” between parents and children evokes the whimsicality of the 60s counterculture while also, like Austin himself, undermining it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.