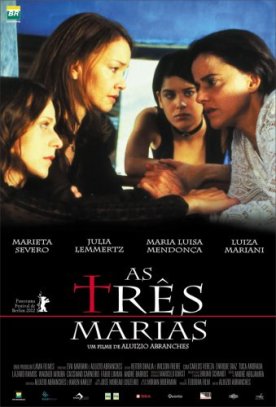

Three Marias, The (As Três Marias)

The Three Marias (As Três Marias) by the Brazilian director, Aluizio Abranches, is the kind of foreign film they used to make back in the 1960s: highly stylized, morally and politically hyper-serious and full of symbolic portent. Filomena (Marieta Severo) refuses the offer of marriage of Firmino Santos Guerra (Carlos Vereza). Instead, she will marry his great enemy, Borges Capadócio and bear him two sons and three daughters, but this is backstory and not part of the film’s narration, which immediately skips over nearly 30 years to show us a disturbing scene of murder. The two thuggish sons of Firmino, José Tranquilo (Cassiano Carneiro) and Arcanjo (Fabio Limma) set Filomena’s son Jono Capadócio (André Barros) on fire, having already murdered his father and brother — whose deaths are represented by iconic shots of their dead bodies.

Filomena calls together her three remaining children, the daughters Maria Francisca (Julia Lemmertz), Maria Rosa (Maria Luisa Mendonça), Maria Pia (Luiza Mariani) and commissions each of them to find a hired killer who is to bring to her the heads of one of the Santos Guerras. Maria Francisca is to seek out Zé das Cobras (Enrique Diaz), a backwoodsman and student of the Bible who refuses to speak to women. He is also by way of being an amateur herpetologist, and he eats snakes with liquor to take away the fear in the blood. Speaking through an intermediary, Catrevagem (Lázaro Ramos), he agrees to undertake the commission to kill Firmino by planting a deadly snake in his bedroom.

Maria Rosa is told to find Chief Tenório (Tuca Andeada), a backwoods policeman and knife specialist who, as she arrives in his village, is out seeking a mad dog on the loose. When he returns he has killed the dog, but he has also been bitten by it and knows he is soon to die. Even so, he suffers from a bad conscience about the illegal act Maria Rosa asks him to commit. She says that, although it is against the laws of man, it is righting a wrong and so will be in keeping with the laws of God. “I ask you to be a saint and kill Arcanjo Santos Guerra”

Maria Pia goes in search of Jesuíno Cruz (Wagner Moura), an obvious madman who calls himself “the devil’s horse” or, alternatively, “God’s vulture,” since “I relieve God of carnage and give the devil something to eat.” He is in prison, but the resourceful Maria Pia contrives to arrange for his escape while he is keeping a dental appointment. Like Zé das Cobras and Filomena, he is God-haunted and tries to account for and justify his calling in religious terms by idiosyncratic readings from the Bible.

Dramatically, this is a classic cinematic situation, set against the wild and primitive landscape of northeastern Brazil, but the treatment of it here is highly stylized and with elements of Latin American “magic realism” and allegory thrown in. The three killers are mildly amusing grotesques, but they have no real purpose except as foils for the daughters, all named for Our Lady, who with their mother suggest a decidedly feminist subtext. For the professional killers with their strutting machismo and Patriarchal religion all fail in their task, and the three resourceful girls show their proud independence as women by learning how to cut off men’s heads for themselves.

This is, as perhaps Gloria Steinem would agree, something that every young girl should know how to do, but their vengeance seems to have lost all connection with those who were to be avenged by the end. What was it all for? “Destiny cheated me,” says Mom, who had thought that the girls’ destiny was not to kill. But that was the way the hitmen crumbled. Typical men! Even as bloody avengers they’re not to be trusted.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.